Background

https://cp-algorithms.com/num_methods/binary_search.html https://usaco.guide/silver/binary-search?lang=py

Binary search is fundamentally simple. The issue is consistently writing it correctly in code. A while ago somebody that’s more maths-y than I am introduced me to the idea of defining invariants, and strictly only using the right-most occurrence or left-most occurrence pattern.

Even Wikipedia has a whole section dedicated to implementation issues here. Donald Knuth said the basic idea is straightforward, but the details are tricky. Jon Bentley also assigned binary search as a problem in a course for professional programmers, and ninety percent of them failed after several hours of working on it.

Method

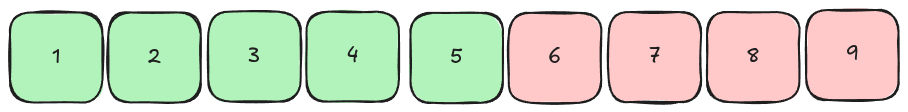

Imagine your dataset as a group of slots like this, and your condition is , or that you’re looking for .

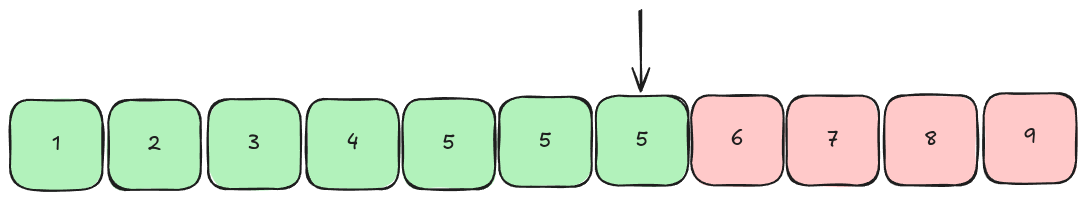

That means you can break it into these two cases

There are obviously some things to note about this when writing code. It means you never want the upper and lower to collide, so your upper needs to start out of bounds and your condition should put them right next to each other in their finishing state. When upper starts out of bounds, it ensures that if 5 is the last element in the list, the lower point still ends on it.

class Solution:

def search(self, nums: List[int], target: int) -> int:

l, u = 0, len(nums)

while u - l > 1:

mid = (l + u) // 2

midv = nums[mid]

if midv <= target:

l = mid

else:

u = mid

return l if nums[l] == target else -1If you feel like increasing your confidence, you can change your while loop into a for loop with 32 iterations.

class Solution:

def search(self, nums: List[int], target: int) -> int:

l, u = 0, len(nums)

for i in range(32):

mid = (l + u) // 2

midv = nums[mid]

if midv <= target:

l = mid

else:

u = mid

return l if nums[l] == target else -1This works because when your left and right are next to each other, they’ll repeatedly do the same thing. 32 iterations is almost nothing, but will work on a list of up to 4 billion elements.

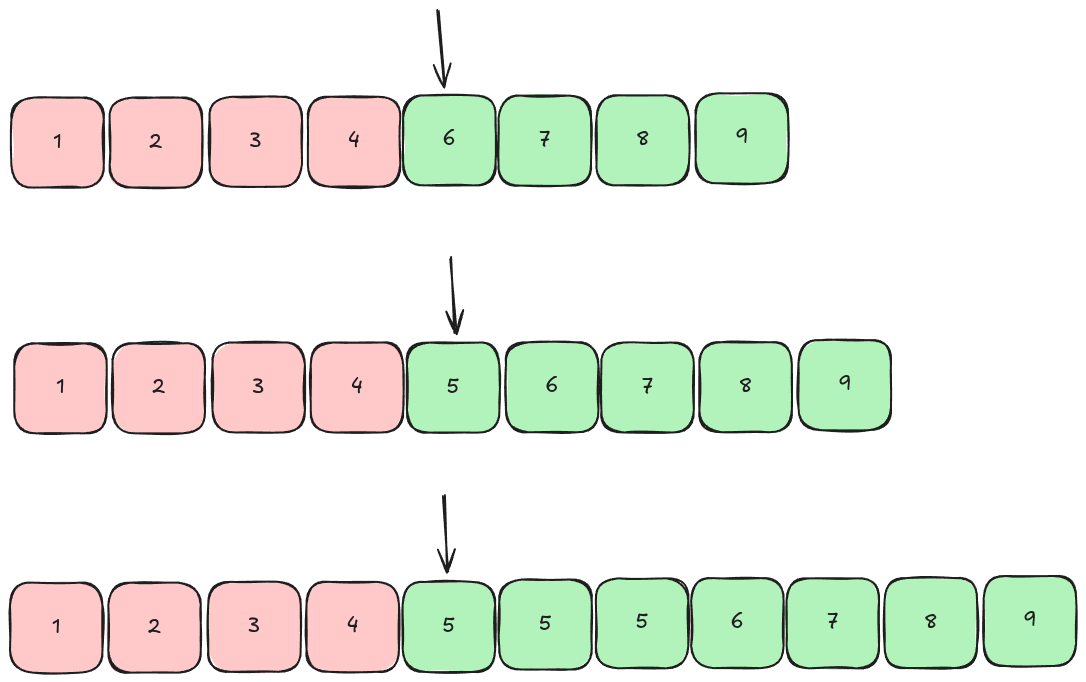

You can further visualise it like this:

If you want to grab the first element, you can subtract one from your initial target then add one on the final result.

Ideally though, you know how your standard library functions work!

Library Functions

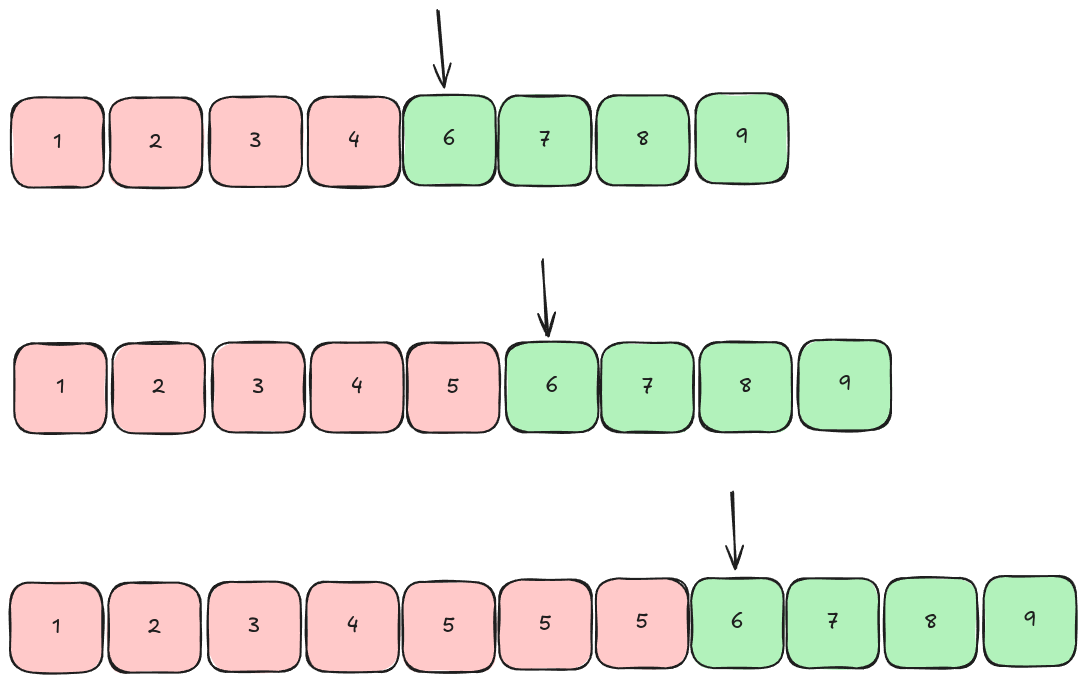

Here are some drawings showing the main versions of the functions I use! It does take a second to adjust to these compared to writing it manually because they work in the opposite order.

lower_bound or bisect_left finds the first element that’s greater than or equal to your value.

// C++

auto it = lower_bound(begin(my_vector), end(my_vector), 5);

// make sure you use this version

// with ordered data structures!

auto it2 = my_set.lower_bound(5); # Python

idx = bisect_left(my_list, 5)

upper_bound or bisect_right finds the first element that’s greater than your value

// C++

auto it = upper_bound(begin(my_vector), end(my_vector), 5);

// make sure you use this version

// with ordered data structures!

auto it2 = my_set.upper_bound(5); # Python

idx = bisect_right(my_list, 5)

Special Binary Searches

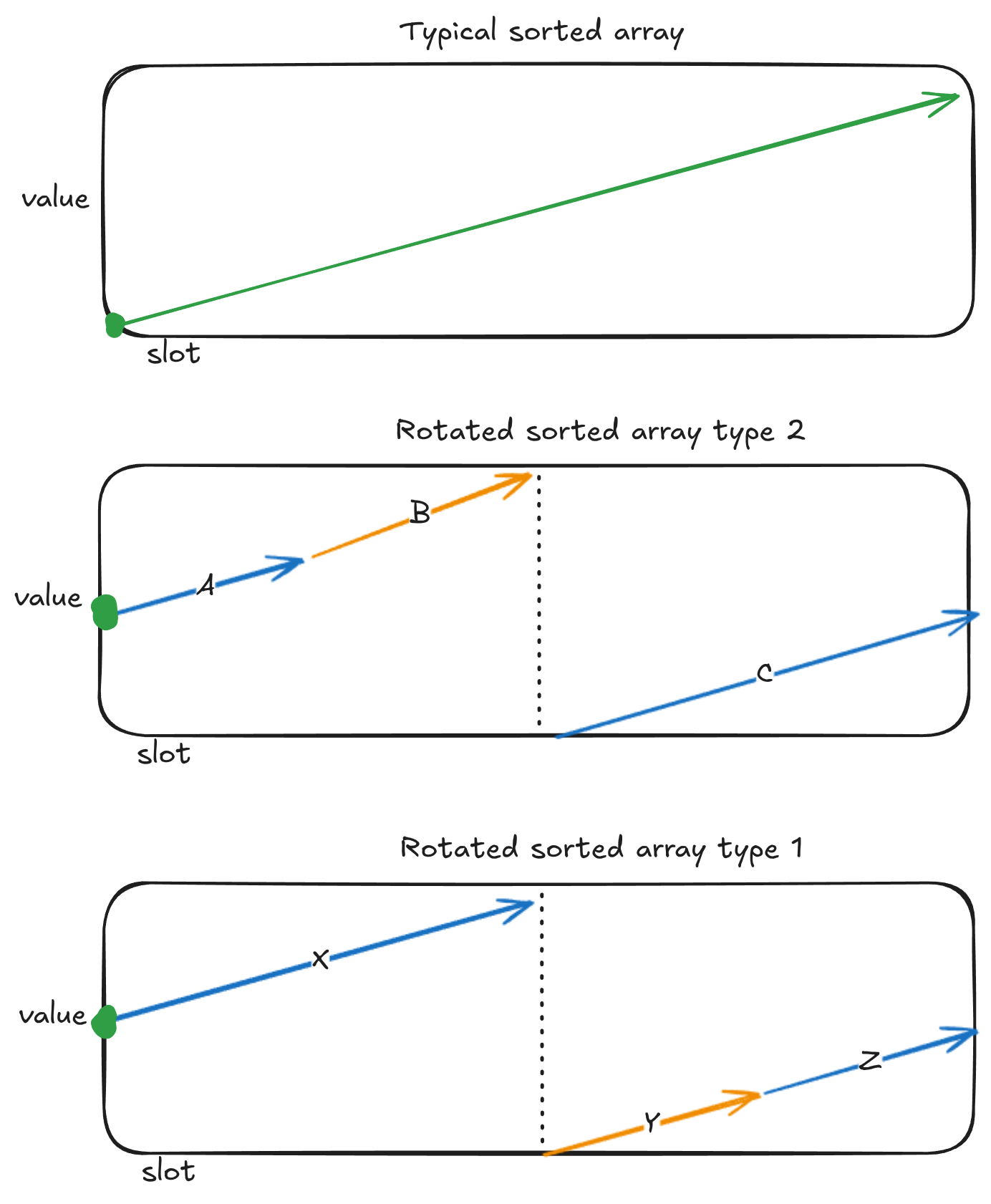

The classic question with a special binary search is Search in Rotated Sorted Array. This sort of visualisation still holds in these scenarios, but your logic is a more cooked. You need to transform the wrong side of the rotation into +- infinity, then do a normal binary search.

Our array will be one of the three types above. Either it’s a regular array, or our target is on the right section (within the orange arrow), or it’s in the left section.

- If our target is greater than the first value in the array, that means our target is in the left area (line B) if it’s rotated, or it’s a typical array.

- If our mid point is less than the first number, that means it must be on the right side (line C), so we need to make this positive infinity.

- If our target is less than the first value, that means it must be type 2, and it must be in the Y line.

- If our mid-point is greater than the first value, that means its in the X line, so we need to make this negative infinity.

If the target is at the end of a second (like at the end of Z), it means the Z line’s length is just zero. Breaking this into cases we have:

class Solution:

def search(self, nums: List[int], target: int) -> int:

l, u = 0, len(nums)

first = nums[0]

while u - l > 1:

mid = (l + u) // 2

x = nums[mid]

if target >= first:

if x < first:

x = 10**10

else: # this makes more sense than doing an elif here

if x >= first:

x = -(10**10)

if x <= target:

l = mid

else:

u = mid

return l if nums[l] == target else -1 zyros

zyros