This is written in the style of a thesis, so it isn’t very fun to read. I already wrote it, so I may as well put it up on here.

Abstract

With the advancement of hardware research, many modern battle-tested databases underutilise their caches and disk read speeds due to being designed when I/O was the bottleneck. This thesis proposes pgx-lower, which demonstrates how just-in-time compilation from a research system can be retrofitted into an established database using its extension system. By integrating LingoDB’s MLIR-based JIT compiler into PostgreSQL, the work adapts columnar in-memory compilation to a disk-oriented architecture while maintaining ACID properties and MVCC support. The evaluations on TPC-H showed improved branch prediction and cache efficiency compared to the original executor. More importantly, pgx-lower demonstrates that a production database can adopt modern compiler techniques as third-party extensions, providing a practical pathway for database research productionisation.

Abbreviations

-

ACID: Atomicity, consistency, isolation, durability

-

API: Application Programming Interface

-

AQP: Adaptive Query Processing

-

AST: Abstract Syntax Tree

-

CPU: Central Processing Unit

-

CTE: Common Table Expression

-

DB: Database

-

DSA: Data Structures and Algorithms

-

EXP: Expression (expressions inside queries)

-

GDB: GNU Debugger

-

GVN: Global Value Numbering

-

IR: Intermediate Representation

-

IPC: Instructions Per CPU Cycle

-

JIT: Just-in-time (compiler)

-

JVM: Java Virtual Machine

-

LICM: Loop Invariant Code Motion

-

LLC: Last Level Cache

-

MLIR: Multi-Level Intermediate Representation

-

MVCC: Multi-Version Concurrency Control

-

OLAP: Online Analytical Processing

-

OLTP: Online Transaction Processing

-

ORC: On-Request-Compilation

-

psql: PostgreSQL

-

QEP: Query Execution Plan

-

RA: Relational Algebra

-

RAM: Random Access Memory

-

SIMD: Single Instruction, Multiple Data

-

SPI: Server Programming Interface

-

SROA: Scalar Replacement of Aggregates

-

SQL: Structured Query Language

-

SSA: Static Single Assignment

-

SSD: Solid State Drive

-

TPC-H: Transaction Processing Performance Council: Decision Support Benchmark H

-

V8: JavaScript Engine (Google Chrome)

Introduction

Databases are a heavily used type of system that rely on correctness and speed. Nowadays, they are often the primary bottleneck in many systems - especially on web servers and other large data applications DDIA. With modern hardware advances, the optimal way to structure these databases has drastically changed, but most databases are using architectures defined by older hardware. Older databases assume the disk operations are the vast majority of runtime, but that has shifted to the CPU for heavy queries.

Research projects typically create standalone databases. However, such approaches make distribution harder, requiring projects to implement all supporting infrastructure themselves. For production projects, supporting infrastructure requires implementing ACID, MVCC, query plan optimisation, and more. By using an established database, we can address this.

pgx-lower (PostgreSQL extension, lowering as in MLIR lowering) replaces PostgreSQL’s execution engine with LingoDB’s compiler to bridge the gap of modern compilers with established systems. The name refers to a PostgreSQL extension that performs MLIR lowering. PostgreSQL’s extension system is utilised to override the executor, and shows features that can be used within PostgreSQL to assist with this research. One concern, however, is the additional complexities in implementation and testing.

The Background chapter covers fundamental concepts and project definition. The Related Work chapter provides a literature survey, followed by the solution in the Method chapter. The result is shown and discussed in the Results and Discussion chapter, and conclusions are drawn in the Conclusion chapter.

Background

Database Background

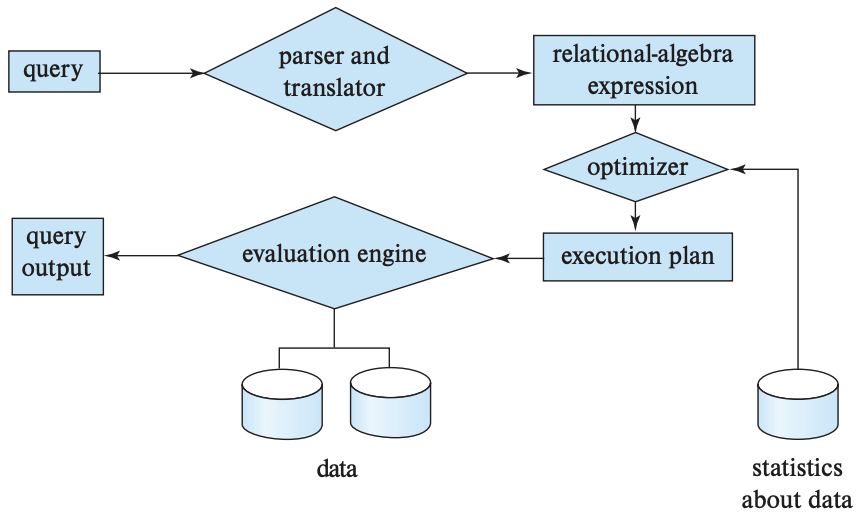

Most databases follow the structure shown in the diagram below, as illustrated in the Background section. Database systems parse Structured Query Language (SQL) into relational algebra (RA), optimise it, execute it, and materialise the results into a table. Database System Concepts.

Non-compiler databases use a volcano operator model tree, such as

Volcano operator tree. A produce()

function at the root node calls its children’s produce(), until it

calls a leaf node, which calls consume() on itself, then that calls

its parent’s consume() function. In other words, a post-order

traversal through the tree where tuples are dragged upwards.

Classical models suffer a fundamental issue: heavy under-utilisation of hardware Ailamaki et al.. If only a single tuple is pulled at a time, the CPU caches are barely used. An i5-760, a popular CPU in 2010, had an 8 MB L3 cache, but in 2024 an i5-14600K has a 24 MB L3 cache PassMark i5-760 benchmark Intel Core i5-760 @ 2.80GHz and TechPowerUp i5-14600K specs Intel Core i5-14600K. For disks, in 2010 the Seagate Barracuda 7200.12 was popular, which had a sustained read of 138 MB/s, but in 2022 the Samsung V-NAND SSD 990 PRO released with a sustained read of 7450 MB/s Seagate Barracuda 7200.12 manual and Samsung 990 PRO datasheet. Such dramatic increases could mean the algorithms can fundamentally change.

These observations led to the vectorized and compiled execution models. The vectorised model pulls multiple tuples up in a group rather than one at a time. A core advantage is that instructions per CPU cycle (IPC) can increase through single instruction, multiple data (SIMD) operations Compiled vs vectorised queries. However, this can cause deep copy operations to be required, or more disk spillage than necessary Vectorised execution vs storage. For instance, if a sort or a join allocates new space that is too large for the cache, the handling can become poor. and The Related Work chapter explore compilation approaches.

Relational databases prioritise ACID requirements - Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation and Durability Database System Concepts. As a critical requirement in database systems, ACID compliance is usually one of the main reasons people choose relational databases DDIA. Atomicity is defined as transactions are a single unit of work, while consistency means the database must be in a valid state before and after the query. Isolation means concurrent transactions do not interact with each other, and durability is defined as once something is committed it will stay committed. Database System Concepts.

Most of the recent database research has focused on the optimiser, which is visible in various research. Common optimisation techniques include reordering join statements (flipping the left and right sides), and predicate push down, where a conditional/filter on a node is moved onto a lower node. PostgreSQL optimisation comparison. Additionally, extracting common subexpressions prevents recomputation, while constant folding evaluates constant operations inside the optimiser rather than at runtime. Despite these advances, query optimisers frequently produce suboptimal plans FishStore (SIGMOD ‘19) Approximate distinct counts. Another essential pattern involves genetic algorithms being used in optimisers for determining things like join orders, which can cause the outputted plan to be non-deterministic. Genetic optimizer study. A thesis could be written just to summarise the list of optimisations.

Within traditional and volcano databases, the cache is managed through buffer techniques. Fixed-size pages (such as eight kilobytes) are read and loaded into a buffer pool object which holds them in RAM. Memory placement in L1/L2/L3 and RAM caches depends on access patterns, and is managed by the operating system or environment Database System Concepts. Buffer pools employ different caching strategies (least-recently-used, most-recently-used, etc.) based on the situation. Buffer management paper. Cache effectiveness can be measured by last level cache hit rate (LLC), which represents how many instructions were served from the CPU cache LLC tuning paper.

Databases are commonly split into Online Transaction Processing (OLTP) and Online Analytical Processing (OLAP). OLTP focuses on supporting atomicity, running multiple queries at once, and typically handles the work profile of an online service that frequently performs key-value lookups. On the other hand, OLAP databases focus on analytical work profiles where aggregations are requested or operations span large chunks of the database DDIA. PostgreSQL implements a hybrid architecture supporting both OLTP and OLAP operations. Hybrid geospatial storage. Debate continues about whether such hybrid designs remain useful, as load pressure on user-serving databases commonly causes reliability issues HTAP is dead.

The layout of database tables within memory is either columnar or tuple/ row-oriented DDIA. In a columnar database, a table is stored as a set of arrays or lists so that when iterated over, only specific columns need to be iterated. This can improve the compression ratio, and horizontal tables can ignore a large number of columns. On the other hand, row-based means that entire-table iteration requires less round-trips and could have better caching in contexts such as joins DDIA. It is common to see columnar databases in OLAP systems and row-oriented in OLTP DDIA.

JIT Background

Just-in-time (JIT) compilers work with multiple layers of compilation such as raw interpretation of bytecode, unoptimised machine code, and optimised machine code. They are primarily used in interpreted languages to improve performance long-masters-thesis. Advanced JIT compilers can run the primary program while background threads improve code optimisation and swap in the optimised version when ready. Privacy integrated queries. Such multi-stage approaches provide faster initial compilation and faster development cycles.

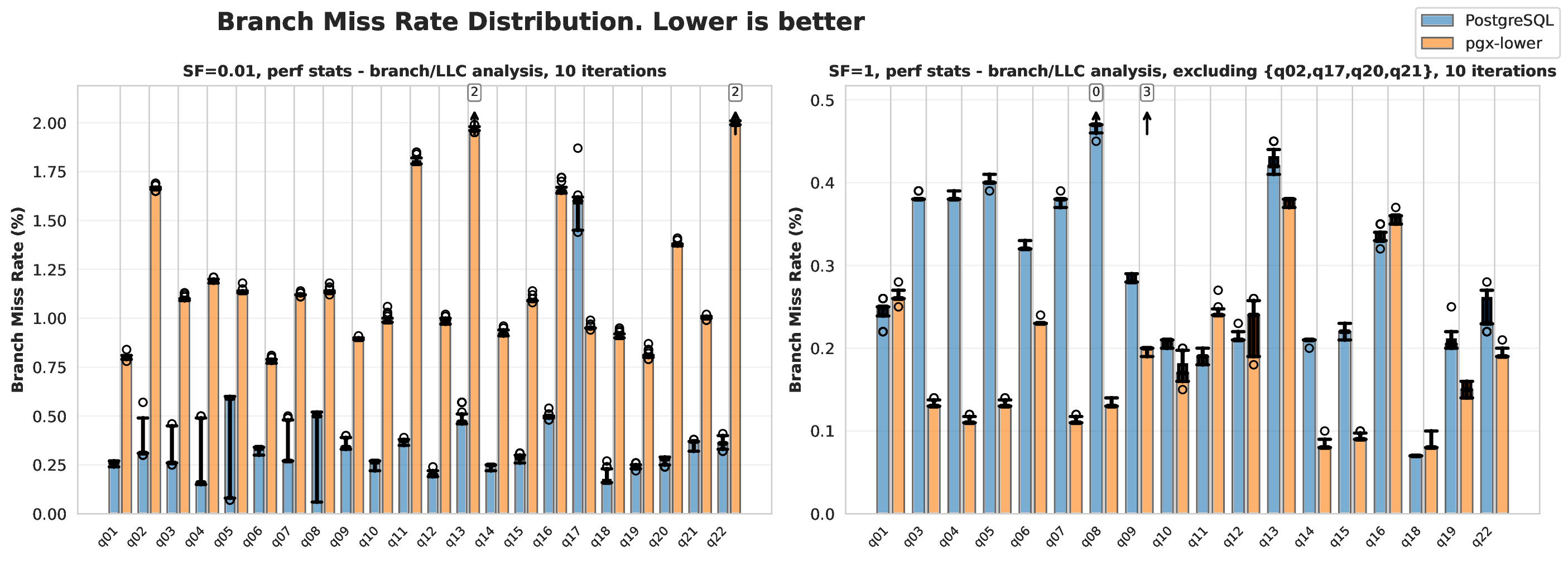

Due to branch-prediction optimisation, JIT compilers can be faster than ahead of time compilers. In 1999, a benchmarking paper measured four commercial databases and found of their execution time was spent fixing poor predictions Early branch misprediction analysis. Modern measurements still find of their query times are spent resolving hardware hazards, such as mispredictions, with improvements in this area making their queries faster Azul JIT perf report. Azul’s JIT compiler measurements also show that speculative optimisations in JIT can lead to performance gains Azul JIT blog.

Defining good branch prediction is difficult. A reasonable baseline is that a misprediction rate is too high and should be optimised in low latency environments Branch prediction guide. Such baselines lack formality and rest on empirical knowledge arxiv.org. Depending on the CPU, a branch mispredict can cost between 10 and 35 CPU cycles, with a typical range being 14-25 cycles Branch misprediction penalty. With 1 branch every 10 instructions and a misprediction rate, a 20 cycle penalty per misprediction translates to approximately of runtime spent resolving mispredictions Branch misprediction penalty.

In the context of databases, compilers fall into two categories: those

that compile only expressions (typically called EXP), and those that

compile the entire Query Execution Plan (QEP) JIT compilation study.

Within PostgreSQL itself, they have EXP support using llvm-jit, but

QEP is not supported. The Related Work chapter examines a variety of research databases.

LLVM and MLIR

The LLVM Project is a compiler infrastructure that eliminates the need to re-implement common compiler optimisations, making it easier to build compilers LLVM paper. LLVM does not stand for anything in particular, and Multi-Level Intermediate Representation (MLIR) is another, newer toolkit that is tightly coupled with the LLVM project MLIR paper. It provides a framework to define custom dialects and progressively lower them to machine code. Developers can define high-level dialects that others can target and build upon.

LLVM defines a language-independent intermediate representation (IR) based on Static Single Assignment (SSA) form, while MLIR extends this concept LLVM paper. SSA is a common layout for IRs where each variable is assigned once and immutable; thus the name. The architecture follows a three-phase design: a front-end parses source code and generates LLVM IR, an optimiser applies a series of transformation passes to improve code quality, and a back-end generates machine code for the target architecture. MLIR extends this concept by introducing a flexible dialect system that enables progressive lowering through multiple levels of abstraction MLIR paper. This addresses software fragmentation in the compiler ecosystem, where projects were creating incompatible high-level IRs in front of LLVM, and improves compilation for heterogeneous hardware by allowing target-specific optimisations at appropriate abstraction levels.

LLVM’s On-Request-Compilation (ORC) JIT is a system for building JIT compilers with support for lazy compilation, concurrent compilation, and runtime optimisation llvm.org. ORC can compile code on-demand as it is needed, reducing startup time by deferring compilation of functions until they are first called. The JIT supports concurrent compilation across multiple threads and provides built-in dependency tracking to ensure code safety during parallel execution. This makes ORC particularly suitable for dynamic language implementations, REPLs (Read-Eval-Print Loops), and high-performance JIT compilers.

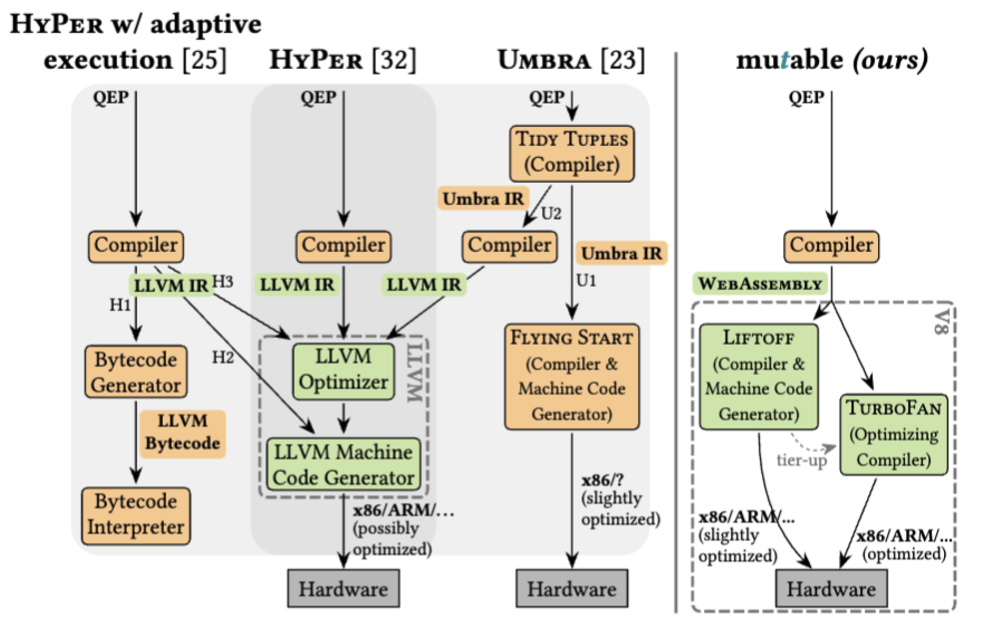

WebAssembly and others

The V8 compiler used for WebAssembly has a unique architecture because it targets short-lived programs. The majority of JIT applications are used for long-running services, but this is used for web pages which are opened and closed frequently. To mitigate this, they have a two-phase architecture where code is first compiled with Liftoff for a quick startup, then hot functions are recompiled with TurboFan webassembly.org. Liftoff aims to create machine code as fast as possible and skip optimisations.

LLVM provides a WebAssembly backend that enables compilation of C and

C++ code to WebAssembly. The compilation process uses clang to make

LLVM IR, which is then processed by the WebAssembly backend to produce

WebAssembly object files. This means C/C++ functions from existing

codebases (such as PostgreSQL) can be pre-compiled to LLVM IR, inlined

into WebAssembly, and then lowered to WebAssembly bytecode

Emscripten WebAssembly backend

Other common JIT compilers are the Java Virtual Machine (JVM), SpiderMonkey (Mozilla Firefox’s JIT), JavaScriptCore/Nitro (Safari/Webkit), PyPy, various python JIT compilers, LuaJIT for Lua, HHVM for PHP, Rubinius for Ruby, RyuJIT for C#, and more War on JITs survey. The JVM has also been used for compiled query execution engines JamDB repo

PostgreSQL Background

PostgreSQL relies on memory contexts, which are an extension of arena allocators. An arena allocator is a data structure that supports allocating memory and freeing the entire data structure. This improves memory safety by consolidating allocations into a single location. A memory context can create child contexts, and when a context is freed it also frees all the children of this context, making this a tree of arena allocators. There is a set of statically defined memory contexts: TopMemoryContext, TopTransactionContext, CurTransactionContext, TransactionContext, which are managed through PostgreSQL’s Server Programming Interface (SPI) PostgreSQL SPI Memory docs

PostgreSQL defines query trees, plan trees, plan nodes, and expression nodes. A query tree is the initial version of the parsed SQL, which is passed through the optimiser, and the output of that is called a plan tree. The nodes in these plan trees can broadly be identified as plan nodes or expression nodes. Plan nodes include an implementation detail (aggregation, scanning a table, nest loop joins) and expression nodes consist of individual operations (binaryop, null test, case expressions) PostgreSQL query tree docs

PostgreSQL provides the EXPLAIN command to inspect query execution

plans, which is essential for understanding and optimising query

performance PostgreSQL EXPLAIN docs. This command displays the execution

plan that the planner generates, including cost estimates and optional

execution statistics, making it a useful tool for database optimisation

and analysis.

PostgreSQL is released under the PostgreSQL Licence, a permissive BSD-like licence that permits free modification, distribution, and commercial use without restriction PostgreSQL Licence. This means editing it or creating commercial extensions is fair use.

Database Benchmarking

Benchmarking a database is difficult because of the variety of

workloads. Many systems create their own benchmarking libraries, such as

pg_bench by PostgreSQL PostgreSQL pgbench docs or LinkBench LinkBench benchmark.

by Facebook, but in academics the more common benchmarks are from the

Transaction Processing Council, which is a group that defines benchmarks

TPC benchmarking overview. Over the years they have made TPC-C for an order-entry

environment, TPC-E, for a broker firm’s operations, TPC-DS for a

decision support benchmark. TPC-H is the most common in research, where

the H informally means “hybrid”. It has a mix of analytical and

transactional elements inside it TPC benchmarking overview.

When evaluating benchmark results, the coefficient of variation (CV) is used. This is a standardised measure of dispersion that expresses the standard deviation as a percentage of the mean Coefficient of variation. It is calculated as , where is the sample standard deviation and is the sample mean. The coefficient of variation is particularly useful when comparing datasets with different units or scales, providing a unit-free measure for variation.

Related Work

We summarise relevant works in the compiled query space and their architectures. Compiled query engines originally dominated the database industry System R paper but the volcano model subsequently took precedence due to its simpler implementation and minimal performance cost at the time. However, modern analytical engines are revisiting compilation approaches Compiled vs vectorised queries

We begin with the OLAP Systems section, then examine the PostgreSQL Background section as the foundation for our work. The System R section covers System R as a classical compiled example, followed by modern compilation approaches in HyPer and Umbra. Research systems Mutable and LingoDB provide relevant architectural insights. The Database Benchmarking section discusses evaluation methodologies, while the literature discusses the remaining background.

OLAP Systems

Compiled query engines primarily benefit OLAP workloads, since OLTP workloads typically involve simpler retrieval queries DDIA. At scale, Apache Hive is commonly used, but it is a data warehouse system rather than a database, storing data in Hadoop’s distributed file system, which is closer to flat storage Apache Hive paper. Common OLAP databases include MonetDB, SnowFlake, ClickHouse, RedShift, and Vectorwise HTAP survey. For our context, understanding ClickHouse, NoisePage, DuckDB and extensions that turn PostgreSQL into an OLAP database are important.

ClickHouse and NoisePage are standalone systems, while DuckDB is embedded and in-process, similar to SQLite. ClickHouse is a columnar, disk-oriented database with a vectorised execution engine and an optional LLVM compilation for expressions (EXP) ClickHouse paper. The Carnegie Mellon Database group created NoisePage, a columnar, in-memory system with full query expression compilation (QEP). They targeted ML-driven self optimisation in their research, but the project was archived on February 21, 2023 NoisePage repo. DuckDB is marketed as the SQLite for analytical loads with in-memory disk spillage, or a more sophisticated Pandas DataFrame DuckDB paper. Their engine supports vectorised execution rather than JIT because JIT would add too much overhead to their lightweight philosophy.

PostgreSQL and Extension Systems

PostgreSQL is a battle-tested system and the most popular database, with of developers in a Stack Overflow survey reporting extensive use in 2024 Stack Overflow DB survey In the context of compiled queries, this means PostgreSQL cannot be treated as a research prototype. Direct modifications to the codebase require extensive testing, and such changes face casual code review via pull requests rather than formal peer review. These pull request reviews can take a long time, sometimes over a year.

Building extensions for PostgreSQL and making companies around these extensions is a common path. Three such examples are Citus Citus paper TimescaleDB Timescale (TigerData) and Apache AGE Apache AGE Citus aims to add more horizontal scaling through sharding, TimescaleDB, now rebranded as TigerData, transforms the engine into a time series database, and Apache AGE turns it into a graph database. All have thousands of GitHub stars, with TimescaleDB especially reporting over 500 paying customers in 2022 and claiming revenue growth by 2024 Timescale funding blog Timescale funding announcement The extension model has proven robust and well-travelled.

There have also been several extensions that attempt to make PostgreSQL more suited to OLAP workloads, with the most relevant one being pg_duckdb pg_duckdb repo pg_duckdb replaces PostgreSQL’s engine with DuckDB, enabling vectorised execution with reasonable popularity at roughly 2700 GitHub stars. Hydra is also worth mentioning, but this is closer to TimescaleDB Hydra columnar extension and makes the system columnar with compression support. ParadeDB’s pg_analytics initially started in the same way as pg_duckdb, but pivoted into supporting search functionality instead, similar to Elasticsearch pg_duckdb repo

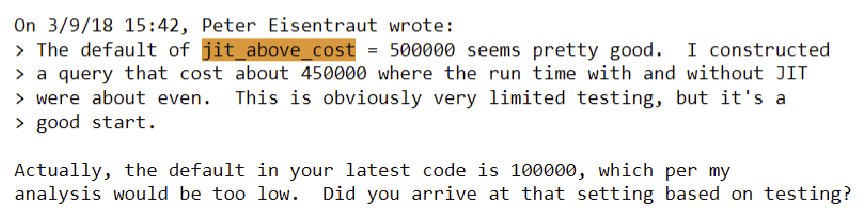

There has been significant discussion about HyPer and JIT in regard to PostgreSQL in 2017 postgresql.org postgresql.org. However, developers expressed doubts about adding full query compilation support, with concerns that rearchitecting such a core component introduces significant risk postgresql.org

However, in September 2017 Andres Freund started implementing JIT

support for expressions PostgreSQL 11 Beta 2 Released They showed that most

CPU time occurs in expression components (such as x > 8 in

SELECT * from table WHERE x > 8;). Furthermore, tuple deformation

provides significant benefits as it interacts with the cache and has

poor branch prediction. PostgreSQL’s JIT implementation is documented in

the official PostgreSQL documentation PostgreSQL JIT docs

In a pull request, Peter Eisentraut questioned whether the default JIT settings were too low postgresql.org Despite this concern, PostgreSQL version 11 released with JIT disabled by default. Limited adoption prompted them to enable JIT by default in later releases to increase exposure and testing opportunities [GSoC] Push-based query executor discussion When released, the United Kingdom’s critical service for COVID-19 dashboards automatically deployed this update and experienced a failure rate, as some queries ran slower dev.to Such failures reinforced the view that JIT features should remain disabled by default, leading to negative perceptions of JIT and compiled queries.

Two implementations of QEP query compilation with PostgreSQL exist, but neither are open source, nor do they have evidence of heavy usage. Vitesse DB, the first implementation, made public posts seeking testing assistance and became generally available in 2015 Vitesse DB announcement While the project remains active with a maintained website Vitesse DB site their TPC-H benchmarks utilise all available CPU cores (32-core systems with two 16-core CPUs) compared to vanilla PostgreSQL’s single-core execution, making direct performance comparisons difficult to assess. This is reasonable though because in an OLAP context, the system can use all the cores, while in an OLTP one it would be handling multiple concurrent requests. Additionally, it remains unclear whether Vitesse DB functions through an extension system allowing existing databases to easily adopt it. PgCon presented a second implementation, achieving speedup on TPC-H query 1 with more extensive documentation PGCon dynamic compilation paper. However, they did not publicise their implementation or show that it is easy for people to use.

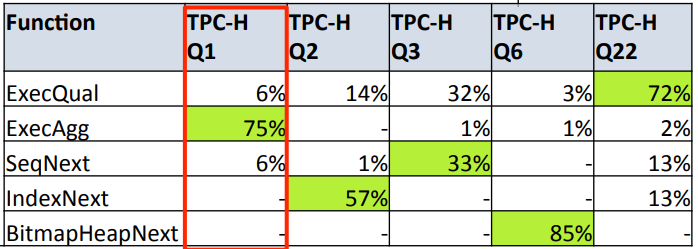

In the presentation, full JIT implementation was preceded by profiling work showing different TPC-H benchmarks pressure in different nodes , enabling informed decisions about optimisation priorities. Their core method is generating a function that represents a node in the plan tree, then inlining the function into the final LLVM IR PGCon dynamic compilation paper in a push-based model. Another interesting method that was used is pre-compiling the C code into LLVM, then inlining that into the LLVM IR. This avoids runtime linking back to the C code PGCon dynamic compilation paper similar to approaches taken by HyPer HyPer compiler paper

Other database systems also support extensions. MySQL, ClickHouse, DuckDB, Oracle Extensible Optimizer all support similar operations. More than just PostgreSQL can be extended in this manner, avoiding the need to create databases from scratch.

System R

System R is a flagship paper in the database space that introduced SQL, compiling engines, and ACID System R paper Their vision described ACID requirements, but was explained as seven dot points as it was not a concept yet. Their goal was to run at a “level of performance comparable to existing lower-function database systems.” Reviewers commented that the compiler is the most important part of the design.

Due to the implementation overhead of parsing, validity checking, and access path selection, a compiler was appealing to them. These features were not supported within the running transactions by default, and they leveraged pre-compiled fragments of Cobol for the reused functions to improve their compile times. Such custom implementation was necessary at the time due to the lack of compiler writing tools. System R shows the idea of compiled queries is as old as databases, and over time the priorities of the systems changed.

HyPer

HyPer was a flagship system, and Umbra supersedes it. These are important systems in the JIT-database space as they developed many of the core features. Both were made by Thomas Neumann, and a core sign of its viability is that Tableau purchased HyPer in 2016 for production use Tableau Hyper acquisition proving that in-memory JIT databases can scale to production workloads. Development began in 2010, with their flagship paper releasing in 2011 for the compiler component HyPer compiler paper and in 2018 they released another flagship paper about adaptive compilation Privacy integrated queries. However, commercialisation poses research challenges since the source code is not accessible, but a binary is available on their website for benchmarking.

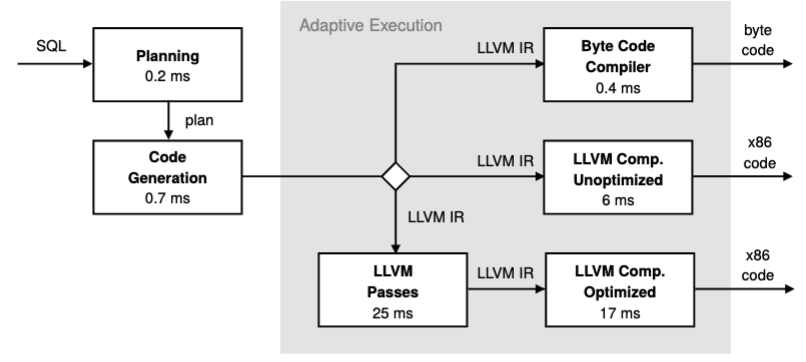

Their 2011 paper on the compiler identifies that translating queries into C or C++ introduced significant overhead compared to compiling into LLVM. As a result, they suggested using pre-compiled C++ objects of common functions then inlining them into the LLVM IR, which is similar to System R’s approach. LLVM’s JIT executor then executes the IR. By utilising LLVM IR, they can take advantage of overflow flags and strong typing which prevented numerous bugs in their original C++ approach.

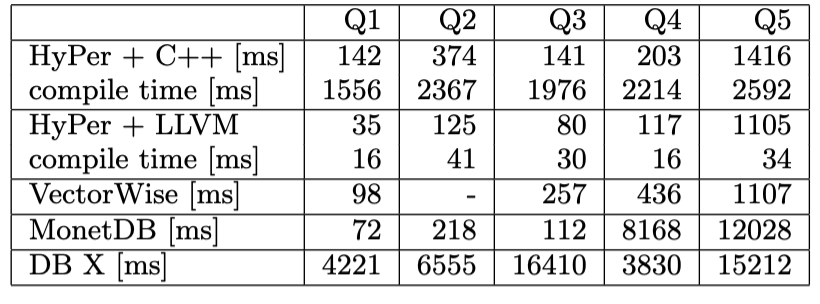

This HyPer reduced compile time by many times. It shows achieved many times fewer branches and branch mispredictions compared to their MonetDB baseline MonetDB/X100 paper. Such improvements resulted from HyPer’s output containing less code in the compiled queries.

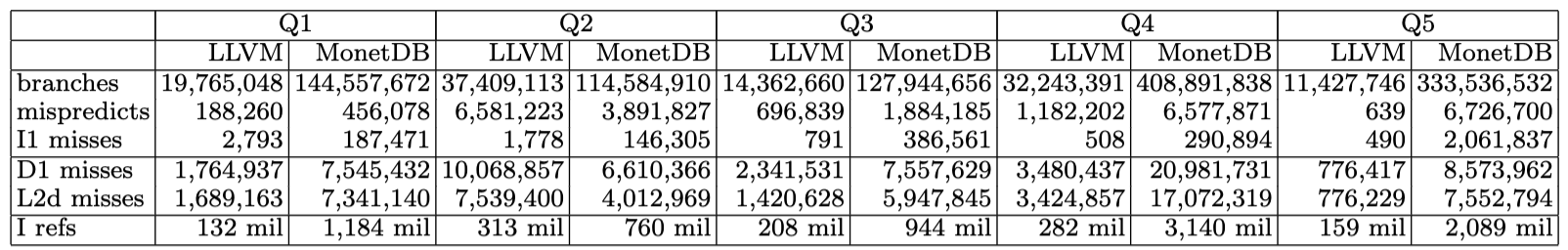

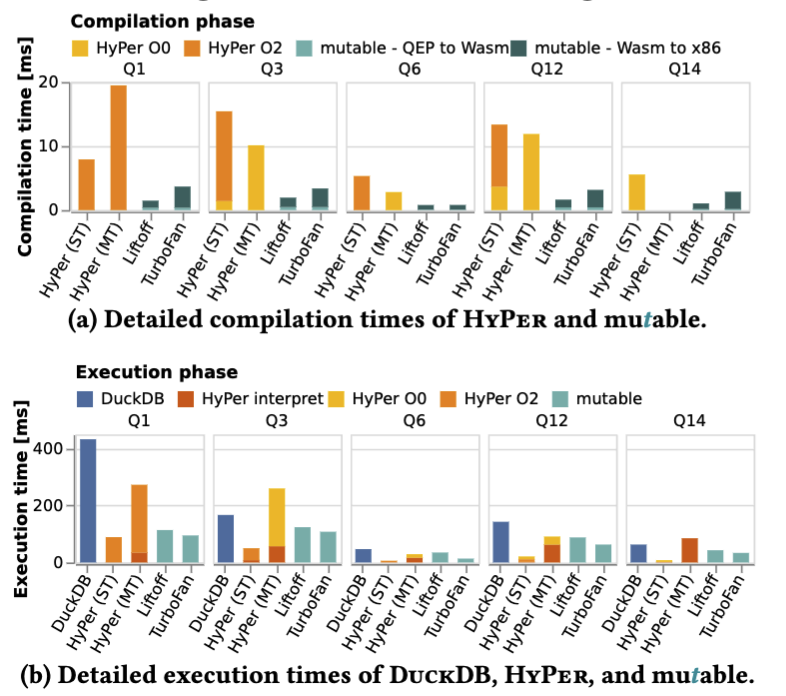

In 2018, HyPer separated the compiler into multiple rounds. An interpreter executes byte code generated from LLVM IR, allowing unoptimised machine code execution in initial stages and optimised machine code in later stages. The visualization illustrates compilation times for each stage. However, they had to create the byte code interpreter themselves to enable this.

The 2018 paper also improved their query optimisation by adding a dynamic measurement for how long-lived queries are taking. The optimiser’s cost model did not lead to accurate enough measurements for compilation timing. Instead, they introduced an execution stage for workers, then in a work-stealing stage they log how long the last job took. With a combination of the measurements and the query plan, they could calculate estimates for jobs and optimal levels to compile them to.

They evaluated this approach using TPC-H Query 11 with 4 threads. The adaptive execution strategy outperformed bytecode-only execution by , unoptimised compilation by , and optimised compilation by . This improvement occurs because the single-threaded compilation can run in parallel with the query executing on another thread.

Utilising additional LLVM compiler stages, improved cost models, and multi-threaded compilation/execution created a viable JIT compiled-query application. The primary criticism is they effectively wrote the JIT compiler from scratch, requiring substantial engineering effort. Most additions are not unique to database JIT compilers; they mostly improved compiler latency.

Umbra

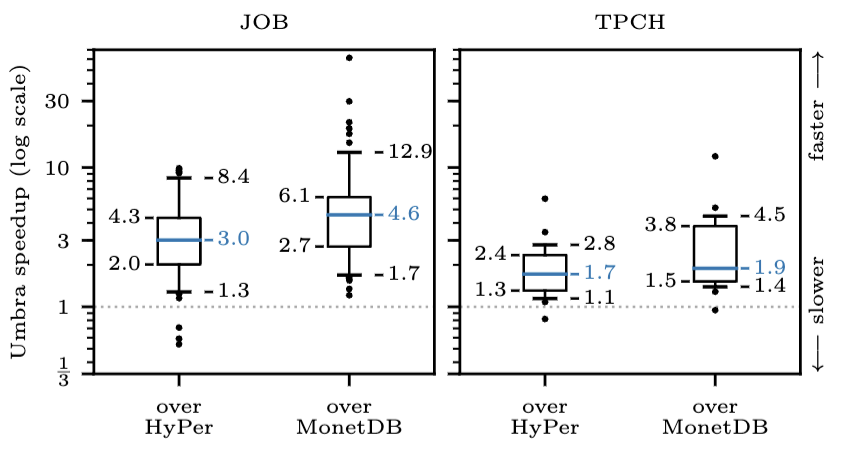

Umbra, created in 2020 by Thomas Neumann (HyPer’s creator), demonstrates that HyPer’s in-memory concepts apply to on-disk systems as well dblp.org Recent SSD improvements and buffer management advances made this possible. Umbra integrates LeanStore’s concepts for buffer management and latching, combined with HyPer’s multi-version concurrency, compilation, and execution strategies. A hybrid approach produced an on-disk database that is scalable, flexible, and faster than HyPer itself. This is visible in the implementation.

They introduced an optimisation enabling the compiler to dynamically change the query plan Adaptive plan change paper Using metrics collected during execution, they swap join order or join types. Such dynamic planning improved data-centric query runtimes by a factor of . Other databases achieve this by invoking the query optimiser multiple times; Umbra’s approach of invoking the compiler once while measuring runtime performance provides additional benefits.

Umbra is currently ranked as the most effective database on ClickHouse’s benchmarks ClickBench benchmark Compiler overhead remains a criticism, but direct JIT compiler access enabling adaptive compilation for optimisation provides distinct advantages. Additionally, Umbra supports user-defined operators, enabling efficient custom algorithm integration Umbra UDF paper

Mutable

In 2023, Mutable presented the concept of using a low-latency JIT compiler (WebAssembly) rather than a heavy one in their initial paper LingoDB MLIR paper Its primary purpose, however, is to serve as a framework for implementing other concepts in database research so that their team does not need to rewrite the framework later Mutable paper. However, using WebAssembly meant they can omit most of the optimisations that HyPer did while maintaining high performance. Furthermore, they have a minimal query optimiser and instead rely on the V8 engine.

V8’s Liftoff component adds early-stage execution to reduce query startup overhead Liftoff performance paper Liftoff produces machine code quickly while skipping optimisations; TurboFan then provides second-stage compilation in the background during execution.

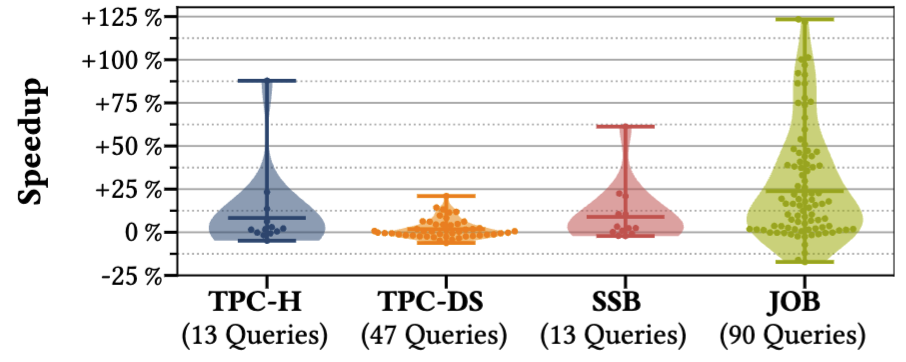

Mutable’s benchmarks show they achieve similar compile and execution times to HyPer, and outperform them in many cases Mutable paper While improving Mutable to the same performance as HyPer or Umbra would require re-architecting, achieving this performance within the implementation effort is a significant outcome.

LingoDB

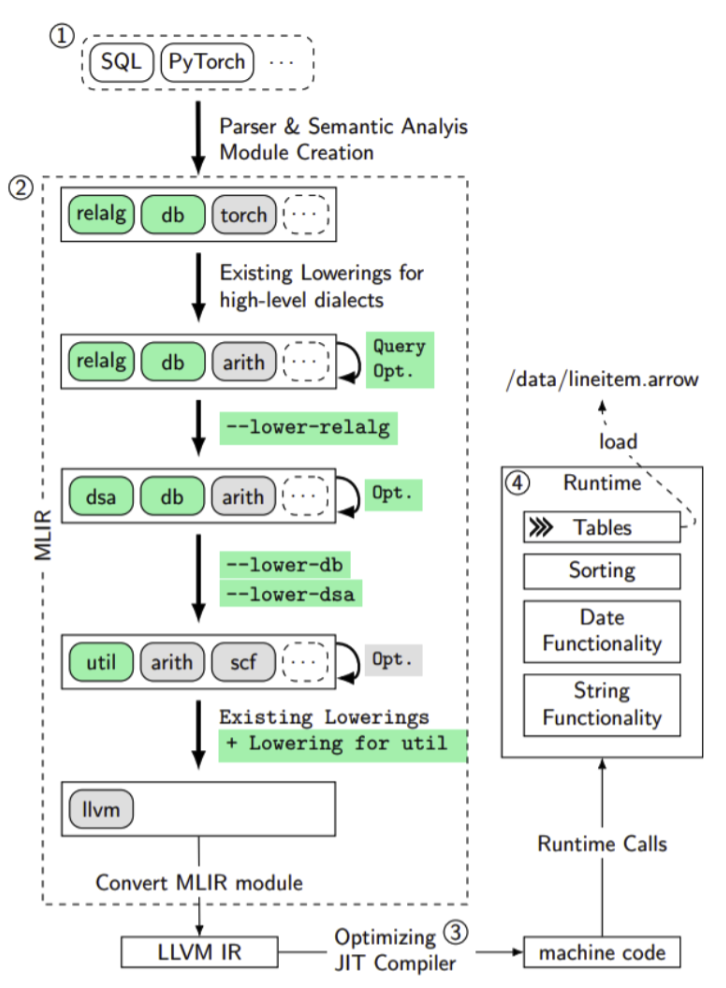

LingoDB, introduced in 2022, proposed using the MLIR framework for optimisation layers LingoDB MLIR paper Traditional databases follow a standard pipeline: parsing SQL into a query tree, converting to relational algebra, optimising using manual implementations, creating a plan tree, and either executing or compiling to a binary. MLIR streamlines this by parsing directly to a high-level MLIR dialect, applying optimisation passes to the dialect, and using LLVM compilation directly without intermediate conversions.

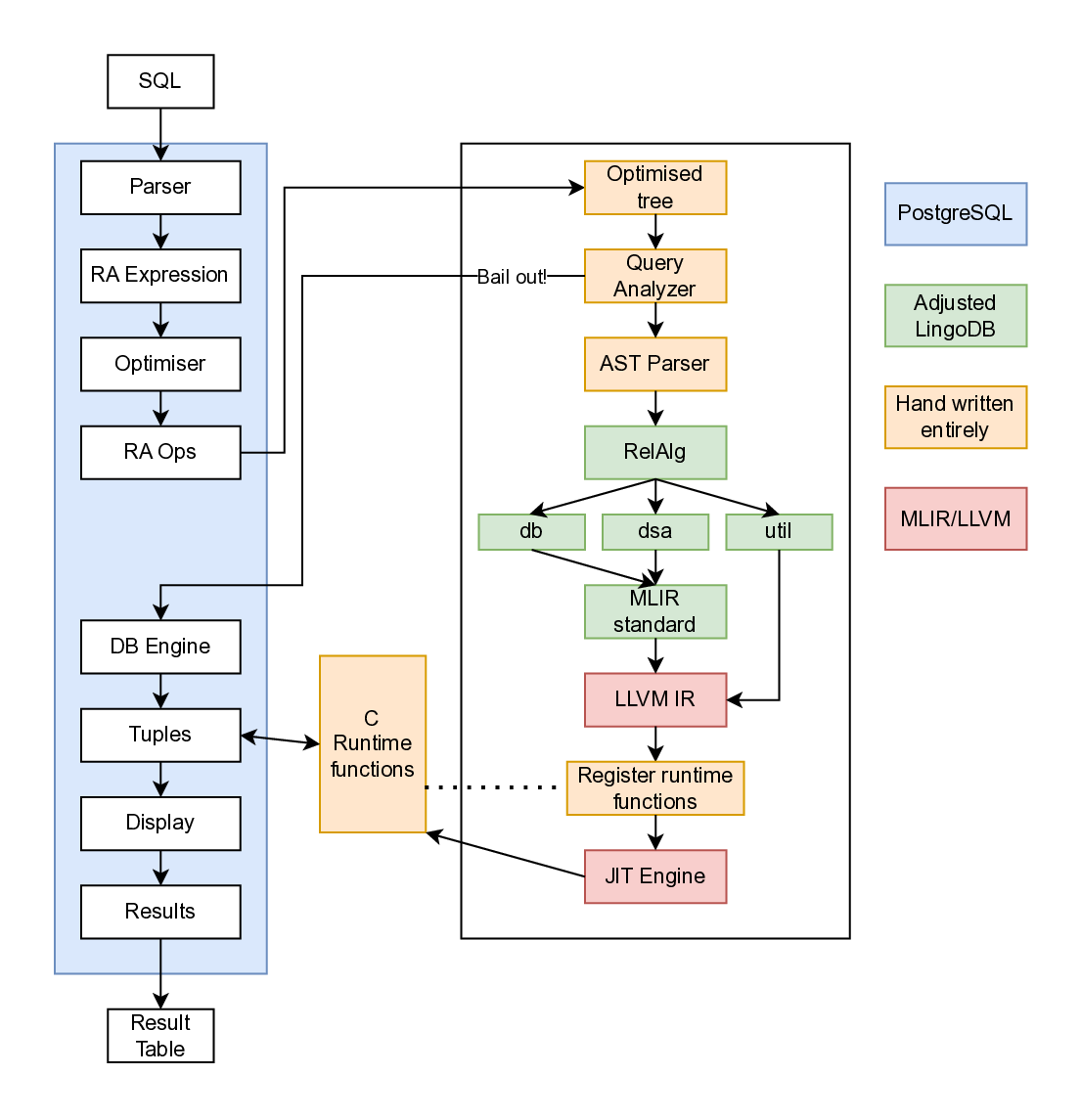

The LingoDB architecture can be seen in the architecture diagram below, which begins by parsing SQL into a relational algebra dialect. MLIR’s dialect system and code generation define these dialects. The compiler consists of multiple dialect layers: a relational algebra dialect for high-level queries, a database dialect for database-specific types and operations, a DSA dialect for data structures and algorithms, and a utility dialect for support functions. This multi-stage design splits the intermediate representation into three levels: relational algebra, a mixed dialect layer, and finally LLVM code LingoDB MLIR paper

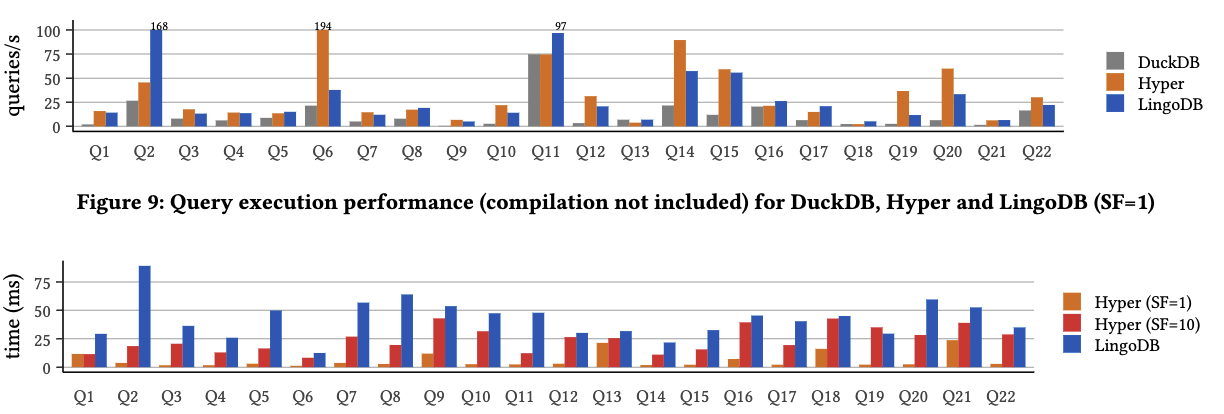

Results in figure [3.11] show worse performance than HyPer but better than DuckDB LingoDB MLIR paper Performance was not the primary focus; rather, implementing standard optimisation patterns within the compiler was key. Notably, LingoDB uses approximately 10,000 lines of code for query execution model, while Mutable uses 22,944 lines despite skipping query optimisation. Comparisons show LingoDB uses three times less code than DuckDB and less than NoisePage.

In later research, LingoDB also explores obscure operations such as GPU

acceleration, using the Torch-MLIR project’s dialect, representing

queries as sub-operators for acceleration, non-relational systems, and

more Torch-MLIR GPU paper For our purposes, the appealing part of their

architecture is that they use pg_query to parse the incoming SQL,

which means their parser is the closest to PostgreSQL’s.

Benchmarking

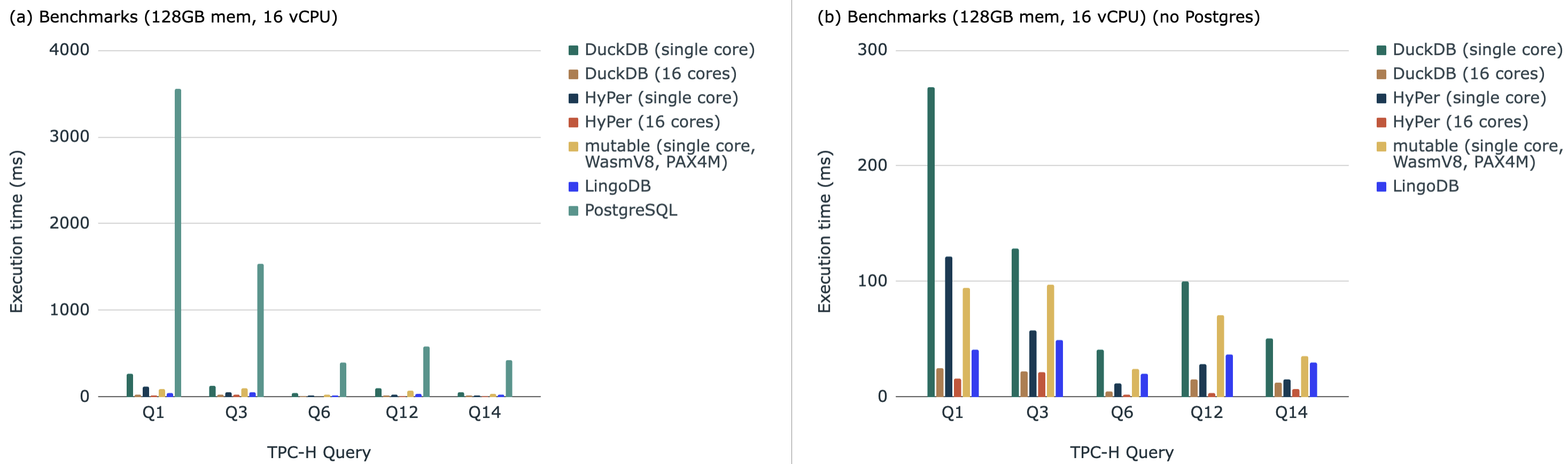

These systems produced their own benchmarks and could selectively pick which systems to involve, so a recreation of the benchmarks was done. DuckDB, HyPer, Mutable, LingoDB and PostgreSQL were all compared to one another, and is visible in the analysis below. These benchmarks used TPC-H because most of the related works used it themselves TPC benchmarking overview and docker containers were chosen to make deploying it easier. These benchmarks were created by relying on the Mutable codebase as they had significant infrastructure to support this, and is visible at benchmarking dockers repo.

The results show that PostgreSQL is significantly slower than the rest, likely because it is an on-disk database and most of the others are in-memory. With PostgreSQL removed from the graph, HyPer and DuckDB are the fastest, but with a single core DuckDB is the slowest.

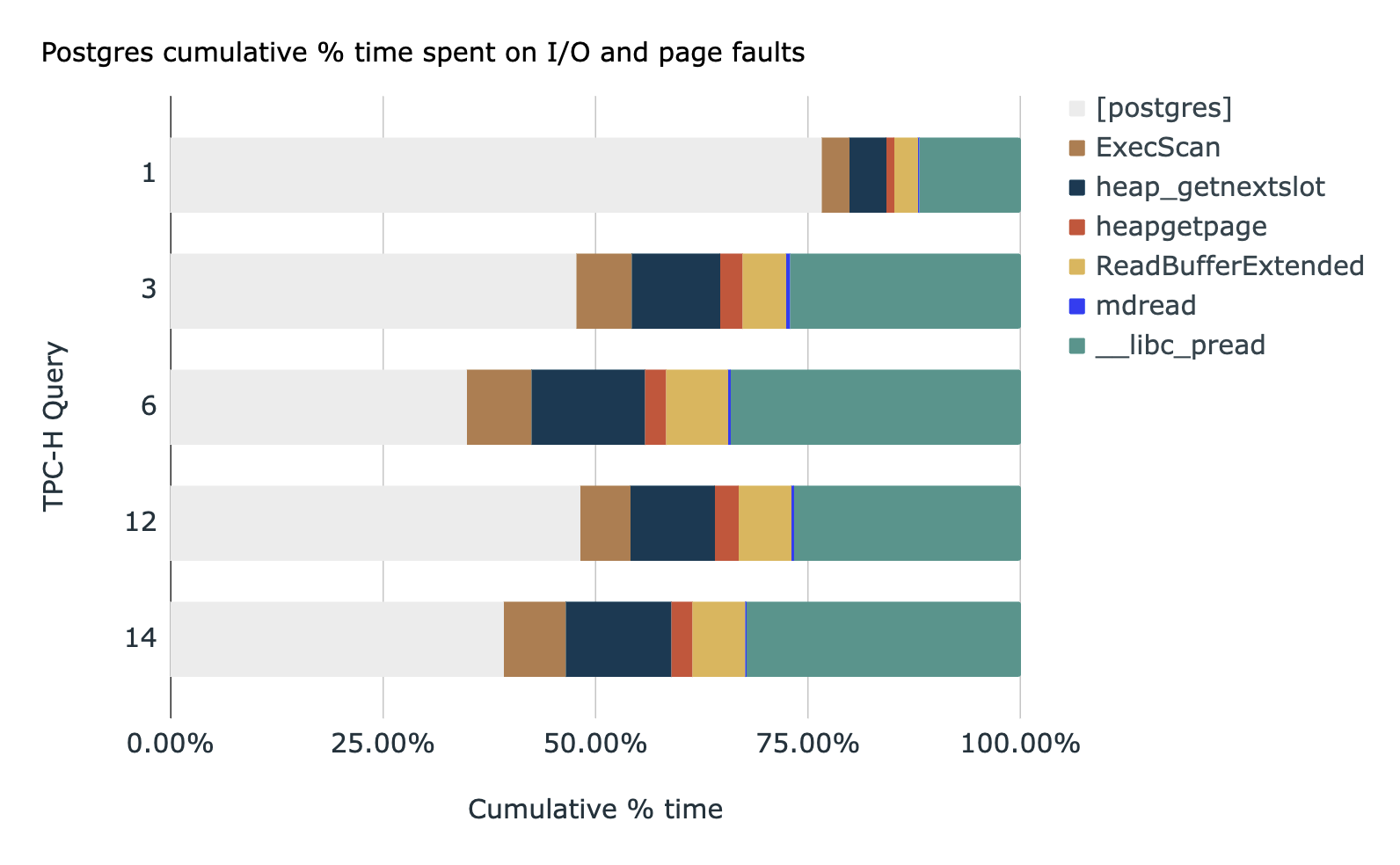

To identify how much potential gain there is in a major on-disk

database, An analysis used perf on PostgreSQL during TPC-H queries 1,

3, 6, 12 and 14 in perf(1) - Linux Manual Page These queries were chosen

because the Mutable code infrastructure directly supported them. This

showed that the CPU time varied from between and ,

with an average of . These metrics were identified using

prof’s output graph. With this much time in the CPU, it is clear that

the queries can become several times faster if optimised.

Gaps in Literature

A core gap is the extension system within an existing database. HyPer and Umbra managed to commercialise their systems, but the other databases are strictly research systems and some do not support ACID, multithreading, or other core requirements such as index scans. Michael Stonebraker, a Turing Award recipient and the founder of PostgreSQL, writes that a fundamental issue in modern research is that they have forgotten the use case of the systems and target the of users Stonebraker industry note These commercial databases reaching high performance is a symptom of this. Testing the wide variety of ACID requirements is a significant undertaking.

The other issue is writing these compiled query engines is a significant amount of work, and the core reason why vectorised execution has gained more popularity in production systems. Debugging a compiled program within a database is challenging, and while solutions have been offered, such as Umbra’s debugger Umbra debugger paper it is still challenging and questionable how transferable those tools are.

Relying on an extension system such that it is an optional feature means users can install the optimisations, and testing can occur with production systems without requesting pull requests into the system itself. Since these are large source code changes, it adds political complexity to get the solution added to the official system without production proof of it being used. The result of this would be a usable database compiler accelerator, that can easily be installed into existing systems, and once it is used in many scenarios it will be easier to add to the official system.

Aims

Tying this together, this piece aims to integrate a research compiler into a battle-tested system by using an extension system. This addresses the gap of these systems being difficult to use widely, and potential to integrate it into the original system once stronger correctness and speed optimisations have been shown. Accomplishing this would show a way to rely on previous ACID-compliant code and supporting code infrastructure. Users can install the extension, have faster queries with rollbacks, and the implementation effort is lowered since core systems and algorithms can be skipped.

A key output is showing that the system can operate within the same order of magnitude as the base system. The purpose of this is to ensure other optimisations can be applied to fit the surrounding database later, but the expectation is not to be faster than it.

One concern is these databases are large systems while the research systems are smaller. This increases the testing difficulty because a complete system has more variables, such as genetic algorithms in the query optimiser that makes performance non-deterministic. To counter this, benchmarks can be executed multiple times, and a standard deviation can be calculated.

Method

The overarching design is described, and the implementation details are covered.

Design

The database and compiler selection requires several criteria: strong

extension support, wide-spread usage, high performance, and a volcano

execution model in the base database. For the compiler, ideally it would

use a similar interface as the base database when parsing SQL,

demonstrate strong performance results, and is open source. Such

criteria eliminates HyPer, Umbra, and System R, leaving Mutable and

LingoDB. LingoDB parses inputs with pg_query, which matches PostgreSQL

well.

As a result, PostgreSQL and LingoDB were selected. PostgreSQL offers strong extension support, enabling runtime hook-based execution engine overrides. TimescaleDB (now TigerData), was discussed in , exemplifies such approaches Timescale (TigerData) A significant challenge arose: LingoDB’s columnar, in-memory architecture required substantial adjustments. Additionally, LingoDB lacks index support, potentially biasing benchmarks against PostgreSQL. LingoDB’s recent versions contain numerous unrequired features and optimisations, so the 2022 version from their initial paper was selected to simplify implementation effort.

An alternative to this could have been a more productionised system such as NoisePage, but this would have increased implementation complexity significantly.

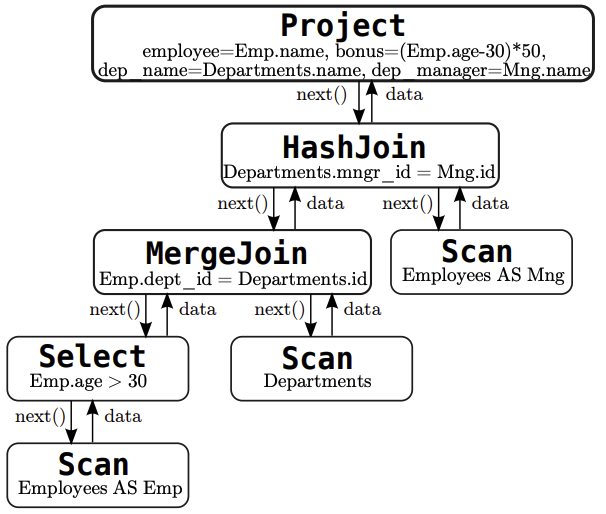

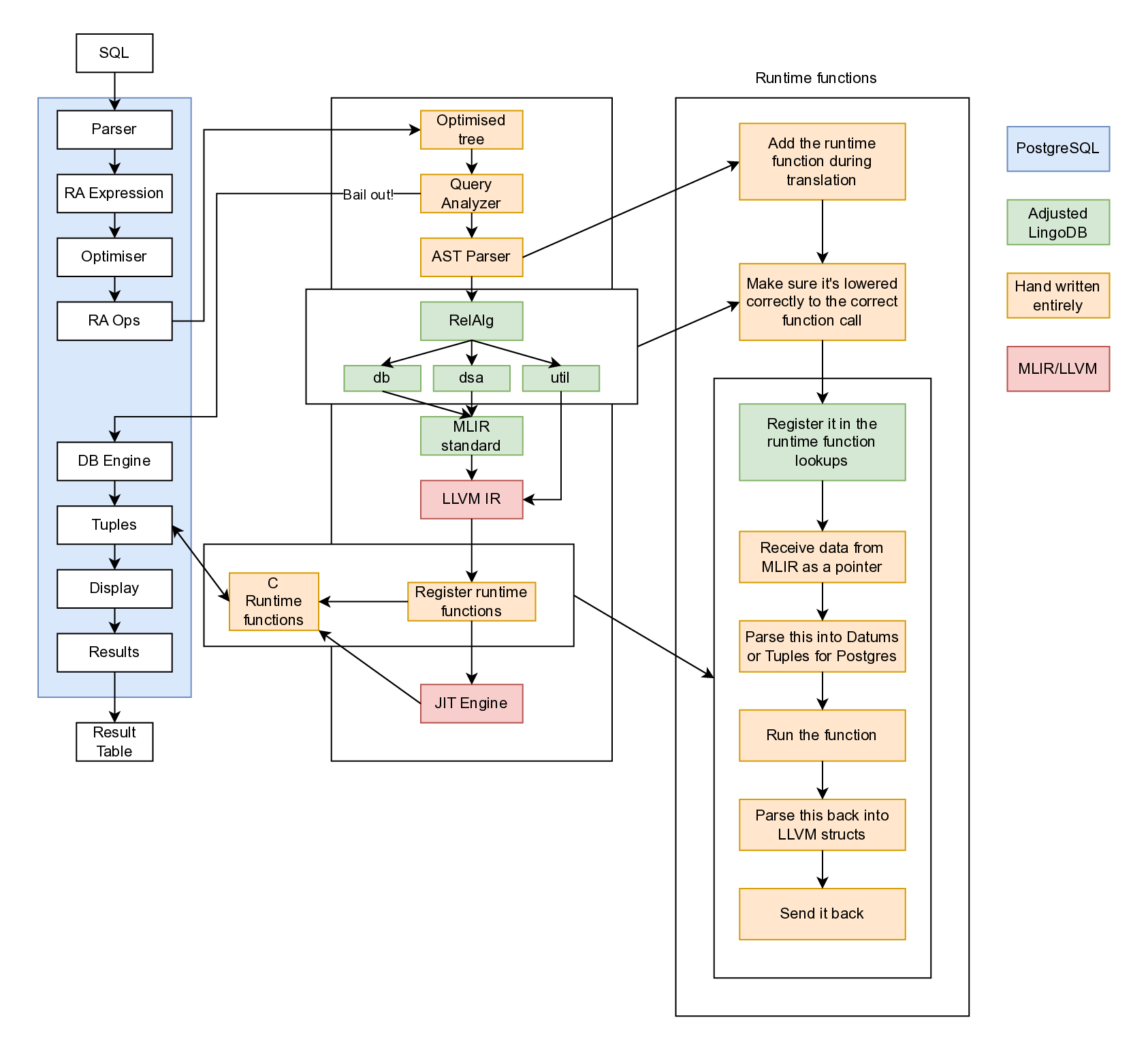

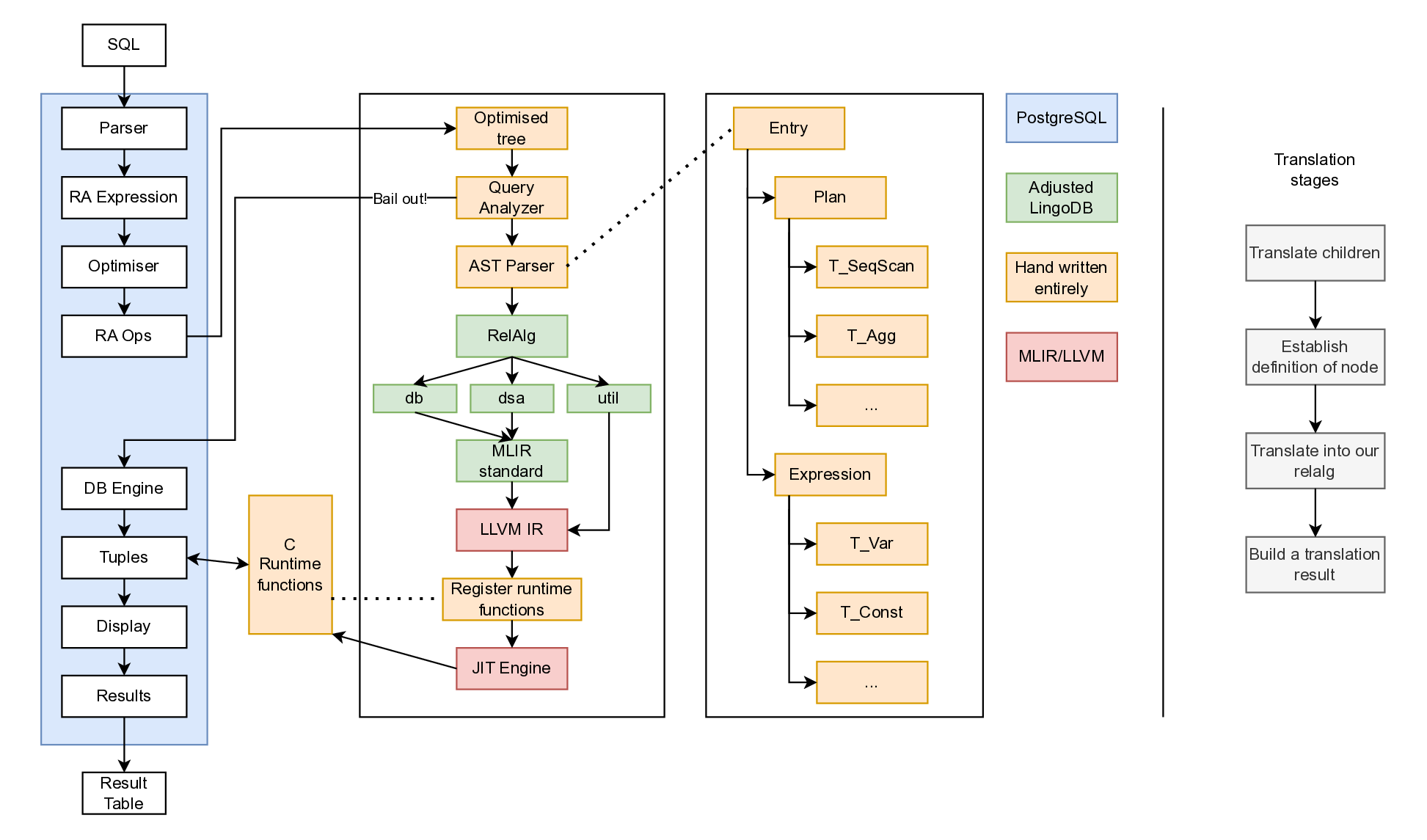

LingoDB is integrated into PostgreSQL as seen in The architecture diagram shows blue components representing PostgreSQL, with the left pipeline showing the entire PostgreSQL execution flow. Queries reach runtime hooks, where a handwritten analyser determines executability before parsing. Handwritten components appear in light-peach. Processing continues through LingoDB code with custom runtime hooks and minor edits, annotated in green. Finally, compilation produces LLVM IR with embedded runtime hooks for PostgreSQL data access.

Query failures should still allow results to return and graceful fallback to PostgreSQL. A try-catch pattern at the AST parser entrance routes failed queries back to PostgreSQL. However, such protection does not prevent system panics such as segmentation faults. When the system does fail from a runtime error, it dumps any accumulated results and completely falls back to PostgreSQL.

AST Parser implementation is expected to be most time-consuming, as it receives the optimised plan tree from PostgreSQL and needs to parse it into the RelAlg dialect. LingoDB was designed to parse query trees from the Parser stage in The implementation diagram includes 18 plan nodes and 14 expression nodes for TPC-H.

TPC-H query support is the final goal. Test-driven development drove

implementation using PostgreSQL’s pg_regress module for SQL query

creation and expected output definition. A progressive test set built

from basic queries up to TPC-H queries. Such progression enabled

incremental node implementation during development and quick validation

of safe changes. Table [4.1] shows the complete regression test

suite, organised to progressively build complexity from single-row

operations to full TPC-H queries.

| File Name | Aim |

|---|---|

1_one_tuple.sql | Single row insertion and selection |

2_two_tuples.sql | Multiple row retrieval |

3_lots_of_tuples.sql | Large dataset handling (5000 rows) |

4_two_columns_ints.sql | Multiple integer columns |

5_two_columns_diff.sql | Mixed column types (INTEGER, BOOLEAN) |

6_every_type.sql | All supported data types with projections |

7_sub_select.sql | Column subsetting across Boolean columns |

8_subset_all_types.sql | Column subsets from multi-type tables |

9_basic_arithmetic_ops.sql | Arithmetic operators (+, -, *, /, %) |

10_comparison_ops.sql | Comparison operators (=, <>, !=, <, ⇐, >, >=) |

11_logical_ops.sql | Logical operators (AND, OR, NOT) |

12_null_handling.sql | NULL operations (IS NULL, COALESCE) |

13_text_operations.sql | Text operations (LIKE) |

14_aggregate_functions.sql | Aggregates without GROUP BY (SUM, COUNT, AVG, MIN, MAX) |

15_special_operators.sql | BETWEEN, IN, CASE WHEN |

16_debug_text.sql | CHAR(10) with LPAD |

17_where_simple_conditions.sql | WHERE with simple comparisons |

18_where_logical_combinations.sql | WHERE with AND/OR/NOT combinations |

19_where_null_patterns.sql | WHERE with NULL checks and COALESCE |

20_where_pattern_matching.sql | WHERE with LIKE and IN operators |

21_order_by_basic.sql | ORDER BY single columns (integers, strings, decimals) |

22_order_by_multiple_columns.sql | ORDER BY multiple columns with mixed directions |

23_order_by_expressions.sql | ORDER BY expressions (not supported - placeholder) |

24_order_by_with_where.sql | ORDER BY combined with WHERE |

25_group_by_simple.sql | GROUP BY with aggregations and ORDER BY |

26_before_check_types.sql | All PostgreSQL types with casts and aggregations |

27_group_by_having.sql | GROUP BY with HAVING clause |

28_group_by_with_where.sql | GROUP BY with WHERE filtering |

29_expressions_in_aggregations.sql | Expressions in aggregates (arithmetic, ABS) |

30_test_missing_expressions.sql | PostgreSQL expression types coverage |

31_distinct_statement.sql | DISTINCT in SELECT and aggregates |

32_decimal_maths.sql | Decimal arithmetic operations |

33_basic_joins.sql | INNER JOIN |

34_advanced_joins.sql | LEFT, RIGHT, SEMI, ANTI joins |

35_nested_queries.sql | Nested and correlated subqueries |

36_tpch_minimal.sql | TPC-H minimal schema variant 1 |

37_tpch_minimal_2.sql | TPC-H minimal schema variant 2 |

38_tpch_minimal_3.sql | TPC-H minimal schema variant 3 |

39_tpch_minimal.sql | TPC-H minimal schema variant 4 |

40_tpch_not_lowered.sql | TPC-H queries without lowering |

41_sorts.sql | Sorting with joins |

42_test_relalg_function.sql | Direct RelAlg MLIR execution |

init_tpch.sql | TPC-H table initialization |

tpch.sql | Full TPC-H benchmark in pgx-lower |

tpch_no_lower.sql | TPC-H inside pure PostgreSQL for validation |

Node implementation ordering followed the dependency analysis. That is, Node implementation ordering followed the dependency analysis. That is, foundational nodes such as the sequential scan and projection are in virtually every query, while other nodes build on top. By implementing in the dependency order, each new node could be tested using the previously implemented nodes, and bugs can be isolated.

Implementation

The primary system this project was developed on was a Ryzen 3600, a x86_64 CPU and on Ubuntu 25.04. The database was not tested on MacOS or Windows, and this may lead to issues when installing it independently.

Integrating LingoDB to PostgreSQL

The project was started from pg_extension bootstrap repo,

then ExecutorRun_hook inside of executor.h in PostgreSQL was used

ExecutorRun_hook definition as the

entrance.

The QueryDesc pointer, containing the query request, was passed from C

to C++. A design decision arose from this requirement: Good practice

would be to use smart pointers to prevent memory leaks, but QueryDesc

is large and the source of truth about the request. Furthermore, the

memory is handled by the PostgreSQL memory contexts. It was decided that

these objects will remain as raw pointers, causing the C++ to break

conventions.

LingoDB is cloned as a git submodule in pgx-lower and set to a read-only permission. This is maintained for reference purposes only, and the compilation phases are extracted from it. LingoDB used LLVM 14, but is upgraded to LLVM 20 to modernise it and bring slightly better support with C++20 (some workarounds were required with LLVM 14 that could be skipped with LLVM 20). However, since this is the C++ API for LLVM, a large amount of the LingoDB code had to be adjusted to compile.

Logging infrastructure

PostgreSQL has its own logging infrastructure that routes through its

elog command, but a two-layer logging infrastructure was required for

pgx-lower. The first layer is the level, (DEBUG, IR, TRACE,

WARNING_LEVEL, ERROR_LEVEL, and more), and the second represents

which layer of the design the log is inside of (AST_TRANSLATE,

RELALG_LOWER, DB_LOWER, and more). This means when the AST

translation is run, all the logs in only that section of the codebase

could be enabled. The core benefit of this is that the logs are lengthy

so it becomes easier to navigate.

Lastly, for error handling mostly std::runtime_error was utilised.

This served as a global way to log the stack trace and roll back to

PostgreSQL’s execution. If an error is thrown in pgx-lower, the progress

in compiling is dumped then it fully falls over to PostgreSQL, even if

the result is half-complete.

Debugging Support

An important property of PostgreSQL is that each client connection creates a new process. Debugging requires navigating several layers: the PostgreSQL postmaster, the client connection, the runtime hook entrance, C++ code, and the JIT runtime. Bugs can occur at any of these levels, making debugging challenging. This poses a particular difficulty when dealing with segmentation faults and other errors that lack logging information.

This was solved with a combination of the regression tests, unit

testing, and a script to connect gdb to dump the stack. The regression

tests were already explained, but the unit tests test components had to

be uncoupled from PostgreSQL. The issue is that this extension creates a

pgx-lower.so which is loaded into PostgreSQL, and the PostgreSQL

libraries are used from that context. This means if we run without being

inside PostgreSQL, no psql libraries can be used. As a result, unit

tests can only test MLIR functions. Most of the unit tests were highly

situational, and are used when a proper interactive GDB connection was

required within the IDE. Furthermore, unit tests allow the stderr to

be visible, which assists greatly with MLIR/LLVM errors that go to

stderr and nowhere else.

For the stack-frame dumping, debug-query.sh was written, which proved

to be the most useful approach for complex issues. It has the ability to

create a psql connection, get the process ID of the client connection,

then connect GDB, run a desired query, and dump the stack trace. In this

way, the majority of errors were tackled.

Data Types

PostgreSQL has a large set of data types

(PostgreSQL data types docs), and LingoDB

has significantly less. However, for TPC-H we only require a subset of

these. Table [4.2] shows which of the LingoDB

types are used, and Table [4.3] shows the type mappings. The two main

changes were to handle decimals and the various types of strings. For

decimals, i128 provides enough precision for most TPC-H tests, which

is what LingoDB was using. However, adjustments had to be made to

prevent precisions that cannot be allocated within an i128 from

appearing, so the precision was capped at <32, 6>. That is, 32 digits

in the integer part and 6 digits in the decimal places.

For date types, when pgx-lower receives a date with a month field it will be turned into the average number of days in a month. This is inaccurate, but since the TPC-H queries never use month intervals, this is acceptable.

| DB Dialect Type | LLVM Type | Used by pgx-lower? |

|---|---|---|

!db.date<day> | i64 | Yes |

!db.date<millisecond> | i64 | No |

!db.timestamp<second> | i64 | Only if typmod specifies |

!db.timestamp<millisecond> | i64 | Only if typmod specifies |

!db.timestamp<microsecond> | i64 | Yes (default) |

!db.timestamp<nanosecond> | i64 | Only if typmod specifies |

!db.interval<months> | i64 | No |

!db.interval<daytime> | i64 | Yes |

!db.char<N> | {ptr, i32} | No (uses !db.string) |

!db.string | {ptr, i32} | Yes |

!db.decimal<p,s> | i128 | Yes |

!db.nullable<T> | {T, i1} | Yes |

| PostgreSQL Type | DB Dialect Type | LLVM Type |

|---|---|---|

| Integers | ||

| INT2 (SMALLINT) | i16 | i16 |

| INT4 (INTEGER) | i32 | i32 |

| INT8 (BIGINT) | i64 | i64 |

| Floating-Point | ||

| FLOAT4 (REAL) | f32 | f32 |

| FLOAT8 (DOUBLE) | f64 | f64 |

| Boolean | ||

| BOOL | i1 | i1 |

| Strings | ||

| TEXT / VARCHAR / BPCHAR | !db.string | {ptr, i32} |

| BYTEA | !db.string | {ptr, i32} |

| Numeric | ||

| NUMERIC(p,s) | !db.decimal<p,s> | i128 |

| Date/Time | ||

| DATE | !db.date<day> | i64 |

| TIMESTAMP | `!db.timestamp<s | ms |

| INTERVAL | !db.interval<daytime> | i64 |

| Nullable | ||

| Any nullable column | !db.nullable<T> | {T, i1} |

The 14 expression node types are documented in

LingoDB Dialect Changes

The MLIR dialects from LingoDB required modifications to support LLVM 20 and pgx-lower’s specific needs. Table [4.4] summarizes the key changes across the DB, DSA, RelAlg, and Util dialects. The changes were primarily API compatibility updates with minimal semantic modifications. The scope included 94 operations in total across all dialects (93 in LingoDB, 94 in pgx-lower) and 21 types (identical count), with most changes addressing LLVM 20 API compatibility.

| Category | Count | Description |

|---|---|---|

| MLIR API Updates | 30 changes | NoSideEffect → Pure, Optional → std::optional, added OpaqueProperties |

| Include Path Changes | 100% of files | mlir/Dialect/ → lingodb/mlir/Dialect/ |

| Dialect Renames | 1 | Arithmetic → Arith (MLIR core change) |

| New Operations | 1 | SetDecimalScaleOp in DSA |

| Modified Operations | 2 | DSA_SortOp (supports collections), BaseTableOp (added column_order) |

| Namespace Clarifications | 6 interfaces | Added explicit cppNamespace declarations |

| Convenience Features | 4 dialects | Added useDefaultTypePrinterParser = 1 |

| Fastmath Support | 2 patterns | Added fastmath flags to arithmetic canonicalization |

| Code Cleanup | 5 locations | Removed comments, simplified logic |

Query Analyser

While the query analyser is fully written, in the final state it routes all queries through pgx-lower for testing. This enables testing new features and identifying where failures occur. It functions by doing a depth-first search through the plan tree and validating that the nodes are supported by the engine. In the future, this component could be enhanced to decide whether a query is worth running based on its cost metrics.

This defines most of the supporting details. The main two components of the implementation are the runtime patterns and the plan tree translation.

Runtime patterns

Runtime functions are used in LingoDB for methods that are difficult to

implement in LLVM, such as sorting algorithms. pgx-lower adds several

custom runtime implementations: reading tuples from PostgreSQL and

storing them for streaming, modifying LingoDB’s runtime implementations,

and replacing the sort and hash table implementations to use

PostgreSQL’s API.

The diagram shows the high-level architecture for runtime processing. During SQL translation to MLIR, the frontend creates

db.runtimecall operations with a function name and arguments. These

operations are registered in the runtime function registry, which maps

each function name to either a FunctionSpec containing the mangled C++

symbol name, or a custom lowering lambda. During the DBToStd lowering

pass, the RuntimeCallLowering pattern looks up each runtime call in

the registry and replaces it with a func.call operation targeting the

mangled C++ function. The JIT engine then links these function calls to

the actual compiled C++ runtime implementations, which handle

PostgreSQL-specific operations like tuple access, sorting via

tuplesort, and hash table management using PostgreSQL’s memory

contexts. This pattern allows complex operations to be implemented once

in C++ and reused across all queries, while maintaining type safety and

null handling semantics through the MLIR type system.

LingoDB had a code generation step in their CMakeLists, gen_rt_def,

which supports generating boilerplate code. It parses a given C++ file,

then generates a header file in the build files which has the mangled

name lookup, so that the developer does not need to reimplement those

sections repeatedly.

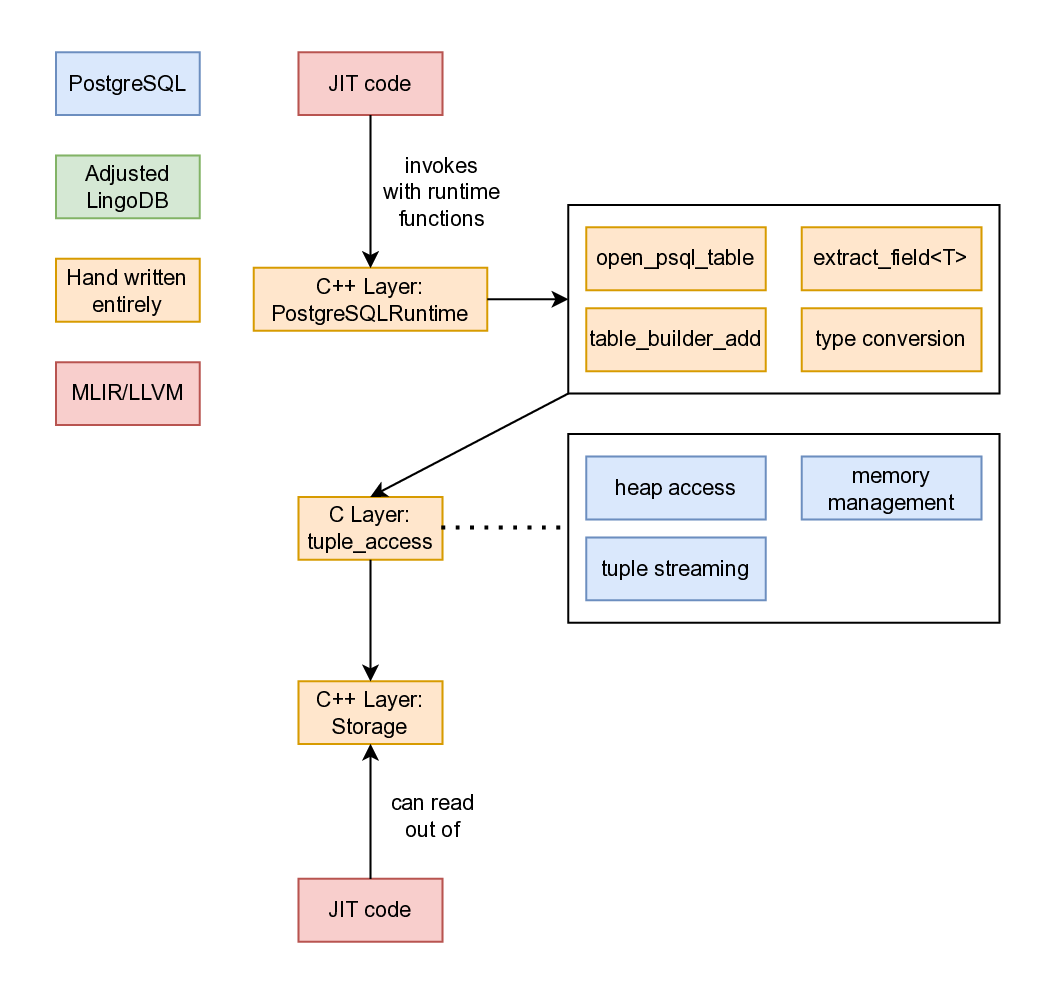

The PostgreSQL runtime implements zero-copy tuple access for reading,

and result accumulation for output. When scanning a table,

open_postgres_table() creates a heap scan using heap_begin_scan(),

and read_next_tuple_from_table() stores a pointer (not a deep copy) to

each tuple in the global g_current_tuple_passthrough structure. JIT

code extracts fields via extract_field(), which uses heap_get_attr()

and converts PostgreSQL Datum values to native types. For results,

table_builder_add() accumulates computed values as Datum arrays in

ComputedResultStorage. When a result tuple completes,

add_tuple_to_result() streams it back through PostgreSQL’s

TupleStreamer by populating a TupleTableSlot and calling the

destination receiver, enabling direct integration with PostgreSQL’s

tuple pipeline.

The PostgreSQL runtime allows the JIT runtime to read from the psql

tables, and the design of it is visible in the design diagram. Generated JIT code invokes runtime

functions implemented in the C++ layer, including table operations

(open_psql_table()), field extraction (extract_field<T>()), result

building (table_builder_add()), and type conversions between

PostgreSQL’s Datum representation and native LLVM types. These runtime

functions interface with PostgreSQL’s C API layer, which handles heap

access for reading tuples, memory management through PostgreSQL’s

context system, and tuple streaming for returning results to the

executor. An important part is that when tuples are read from Postgres,

only the pointers are stored within the C++ storage layer to maintain

zero-copy semantics.

Once stored, the JIT code can read from the batch and stream tuples back through the output pipeline as well. Streaming the tuples out from JIT means that the entire table does not build up in RAM, and instead tuples are returned one by one. This was tested by doing larger table scans as avoiding this buildup is essential.

LingoDB’s sort and hashtable runtimes were relying on std::sort and

std::unordered_map respectively. This is problematic because as an

on-disk database we need to handle disk spillage in these scenarios.

Rather than reinventing these, leaning on psql’s implementation of these

solves these issues and creates a blueprint for further implementations.

Most of the LingoDB lowerings bake metadata (such as table names) into the compiled binary by JSON-encoding it as a string. Instead of that, for the sort and hash table runtimes a specification pointer was used. Inside the plan translation stage, a struct was built and allocated with the transaction memory context, then the pointer to this was baked into the compiled binary instead. This enabled these runtimes to trigger without doing JSON serialisation and deserialisation. This is something that a regular compiler would be incapable of doing, because the binary needs to be a standalone program, but in this context it can be relied upon.

Plan Tree Translation

The plan tree translation converts PostgreSQL’s execution plan nodes into RelAlg MLIR operations. The architecture shows where this fits into the broader design. Within the AST Parser component, we examine the PostgreSQL tag on the node to determine the plan node type, then a recursive descent parser starts translating. Each translation function follows a consistent pattern. First, children of the plan are translated using post-order traversal. Then, the node is translated into the MLIR relational algebra dialect, and a translation result is built then returned.

The translation functions follow a consistent pattern, as shown in the code below. Each function takes the query

context and a PostgreSQL plan node pointer, performs the translation,

and returns a TranslationResult. The QueryCtxT object is passed down

the tree, and when mutated, a new instance is created for child nodes.

Meanwhile, TranslationResults flow upward to represent each node’s

output, providing strong type-correctness in theory. However, this

pattern is not strictly enforced in practice.

auto translate_plan_node(QueryCtxT& ctx, Plan* plan) -> TranslationResult;

auto translate_seq_scan(QueryCtxT& ctx, SeqScan* seqScan) -> TranslationResult;

auto translate_index_scan(QueryCtxT& ctx, IndexScan* indexScan) -> TranslationResult;

auto translate_index_only_scan(QueryCtxT& ctx, IndexOnlyScan* indexOnlyScan) -> TranslationResult;

auto translate_bitmap_heap_scan(QueryCtxT& ctx, BitmapHeapScan* bitmapScan) -> TranslationResult;

auto translate_agg(QueryCtxT& ctx, const Agg* agg) -> TranslationResult;

auto translate_sort(QueryCtxT& ctx, const Sort* sort) -> TranslationResult;

auto translate_limit(QueryCtxT& ctx, const Limit* limit) -> TranslationResult;

auto translate_gather(QueryCtxT& ctx, const Gather* gather) -> TranslationResult;

auto translate_gather_merge(QueryCtxT& ctx, const GatherMerge* gatherMerge) -> TranslationResult;

auto translate_merge_join(QueryCtxT& ctx, MergeJoin* mergeJoin) -> TranslationResult;

auto translate_hash_join(QueryCtxT& ctx, HashJoin* hashJoin) -> TranslationResult;

auto translate_hash(QueryCtxT& ctx, const Hash* hash) -> TranslationResult;

auto translate_nest_loop(QueryCtxT& ctx, NestLoop* nestLoop) -> TranslationResult;

auto translate_material(QueryCtxT& ctx, const Material* material) -> TranslationResult;

auto translate_memoize(QueryCtxT& ctx, const Memoize* memoize) -> TranslationResult;

auto translate_subquery_scan(QueryCtxT& ctx, SubqueryScan* subqueryScan) -> TranslationResult;

auto translate_cte_scan(QueryCtxT& ctx, const CteScan* cteScan) -> TranslationResult;The 14 expression node types are documented in Table [4.5], and the 18 plan node types in Table [4.6]. The subsections explain these more specifically.

| File | Node Tag | Implementation Note |

|---|---|---|

| basic | T_BoolExpr | Boolean AND/OR/NOT - with short-circuit evaluation |

| basic | T_Const | Constant value - converts Datum to MLIR constant |

| basic | T_CoalesceExpr | COALESCE(…) - first non-null using if-else |

| basic | T_CoerceViaIO | Type coercion - calls PostgreSQL cast functions |

| basic | T_NullTest | IS NULL checks - generates nullable type tests |

| basic | T_Param | Query parameter - looks up from context |

| basic | T_RelabelType | Type relabeling - transparent wrapper |

| basic | T_Var | Column reference - resolves varattno to column |

| complex | T_Aggref | Aggregate functions - creates AggregationOp |

| complex | T_CaseExpr | CASE WHEN … END - nested if-else operations |

| complex | T_ScalarArrayOpExpr | IN/ANY/ALL with arrays - loops over elements |

| complex | T_SubPlan | Subquery expression - materializes and uses result |

| functions | T_FuncExpr | Function calls - maps PostgreSQL functions to MLIR |

| operators | T_OpExpr | Binary/unary operators |

| File | Node Tag | Implementation Note |

|---|---|---|

| agg | T_Agg | Aggregation - AggregationOp with grouping keys |

| joins | T_HashJoin | Hash join - InnerJoinOp with hash implementation |

| joins | T_MergeJoin | Merge join - InnerJoinOp with merge semantics |

| joins | T_NestLoop | Nested loop join - CrossProductOp or InnerJoinOp |

| scans | T_BitmapHeapScan | Bitmap heap scan - SeqScan with quals |

| scans | T_CteScan | CTE scan - looks up CTE and creates BaseTableOp |

| scans | T_IndexOnlyScan | Index-only scan - treated as SeqScan |

| scans | T_IndexScan | Index scan - treated as SeqScan |

| scans | T_SeqScan | Sequential scan - BaseTableOp with optional Selection |

| scans | T_SubqueryScan | Subquery scan - recursively translates subquery |

| utils | T_Gather | Gather workers - pass-through (no parallelism) |

| utils | T_GatherMerge | Gather merge - pass-through (no parallelism) |

| utils | T_Hash | Hash node - pass-through to child |

| utils | T_IncrementalSort | Incremental sort - delegates to Sort |

| utils | T_Limit | Limit/offset - LimitOp with count and offset |

| utils | T_Material | Materialize - pass-through (no explicit op) |

| utils | T_Memoize | Memoize - pass-through to child |

| utils | T_Sort | Sort operation - SortOp with sort keys |

There are several common node definitions which are helpful to

There are several common node definitions which are helpful to

understand. Nodes commonly have an InitPlan parameter, which is a

function called before the node executes and initialises variables such

as parameters and catalogue lookups. targetlist contains the output of

the node, and qual specifies which tuples should pass through. Join

nodes have left and right child trees, typically referred to as inner

and outer children. These signify the inner and outer loops of the

nested for-loop that is created.

Expression Translation - Variables, Constants, Parameters

PostgreSQL identifies values using variable nodes and parameter nodes.

These are tracked in a schema/column manager class and the QueryCtxT

object. Variables are typically defined within scans, while parameters

are intermediate products. Identifying them presented challenges due to

multiple interacting identifiers (varno, varattno, and special

values for index joins). To handle this complexity, a generic function

was added to the QueryCtxT object: resolve_var. This function is used

extensively throughout the translation logic.

Parameters are mostly defined within the InitPlan, and one key type is the cached scalar type.

Plan translation - Scans

PostgreSQL supports multiple scan types: sequential scans, subquery scans, index scans, index-only scans, bitmap heap scans, and CTE scans. However, all scan types except subquery and CTE scans route to sequential scans in this implementation. This trade-off reduces implementation complexity at the cost of query performance, particularly for index scans.

Index scans use special annotations for variables via INDEX_VAR, which

requires custom variable resolution. Additionally, we handle the

qualifiers (scan filters) indexqual and recheckqual as generic

filters. In PostgreSQL, these qualify at different stages, but since we

skip index implementation, both become generic filters.

CTE scan plans are defined within the InitPlan of nodes, but still route through the primary plan switch statement logic. Neither CTE plans nor subqueries currently offer de-duplication to simplify implementation. That is, if a query uses the same CTE reference or writes the same subquery twice, they will currently be lowered into two different LLVM chunks of code rather than congregated and referenced.

Plan translation - Aggregations

Aggregation is a complicated node type with many properties. It includes an aggregation strategy (ignored in pgx-lower in favour of a simpler algorithm), splitting specification (not utilised), and group columns. The node tracks the number of groups it produces and manages its own operators such as COUNT, SUM, and more. Additionally, it uses special varnos for variable lookups (represented as -2), requiring a new context object, and supports DISTINCT statements.

Most of the pain was with specific edge cases that arise in the

simplification. For instance, COUNT(*) behaves differently in

combining mode where parallel workers provide partial counts rather than

raw rows, requiring translation to SUM instead of CountRowsOp.

Similarly, HAVING clauses can reference aggregates not present in the

SELECT list, necessitating a discovery pass with find_all_aggrefs() to

ensure all required aggregates are computed before filtering. The use of

varno=-2 to identify aggregate references, while necessary to

distinguish them from regular column references, breaks the normal

variable resolution flow and requires special handling throughout the

expression translator.

Plan translation - Joins

For joins, two layers exist for translation: the type of join, and the

algorithm used by the join. The type of join refers to inner, semi,

anti, right-anti, left/right joins, and full joins. The semi and anti

join types are not specifically translated, and instead rely on

EXISTS/ NOT EXISTS translations because they are semantically the

same operation.

The algorithm used by the join refers to merge, nestloop, or hash joins. Following LingoDB’s pattern, the merge joins are turned into hash joins so that there does not have to be additional lowering code. A challenge was that nest loops can carry parameters, so a new query context has to be created, the parameter has to be registered and inserted into the lookups.

One issue in the joins implementation is preventing double computations. LingoDB handles this by computing the inner join separately, building a vector of results, and then iterating over the outer operation while reusing the pre-computed inner section. This approach prevents duplicated computation at the cost of increased memory usage. While theoretically acceptable, the vector would need to implement disk spillage. In practice, memory usage did not become problematic enough to require this feature.

Expression Translation - Nullability

PostgreSQL tracks nullability information in the plan tree passed to pgx-lower. However, LingoDB’s lowering operations can create situations where previously n on-null objects become nullable through outer joins, aggregations, unions, and predicate evaluation. Since nullability propagates like not-a-number (affecting everything it touches), this introduces significant implementation complexity.

One note to be aware of is that LingoDB and PostgreSQL have inverted null flags. That is, in LingoDB 1 means valid, and in PostgreSQL 1 means null. This causes confusion with the runtime functions needing to invert the flags back and forth.

Expression Translation - Operators and OID strings

Within operators, the primary challenge is the type conversions and

quirks. Comparing two BPCHARs requires adding padding for the

surrounding space. To implement implicit upcasting, a class was

extracted from LingoDB’s DB dialect: SQLTypeInference. Rather than

relying on PostgreSQL’s OID system for finding operations, operators are

converted to strings (e.g., ">" and "<") for lookups. This prevents

issues with OID precision specifications that lead to unidentified

operations. The same approach is used in function nodes, aggregation

functions, sort operations, and scalar maths. When performing operations

on different types, SQLTypeInference upcasts the smaller operand to

the larger datatype. For example, with i16 + i32, i16 is cast to

i32.

Translation - Others

Many of these nodes are pass through nodes or delegated to another,

sibling node, such as T_Hash, T_Material, T_Memoize, and

T_RelabelType. Furthermore, nodes also come with executor hints and

cost metrics which were skipped over rather than dragged through

LingoDB, as the optimisations were already done by Postgres. IN/ANY

operations are also converted into EXISTS operations, several operations

such as scalar subqueries are always marked as nullable, and CastOps are

also made frequently to defer casting to later layers.

Configuring JIT compilation settings

Not much tinkering was done with the JIT optimisation flags; the minimum

optimisation passes were used so that it can run end-to-end, and

llvm::CodeGenOptLevel::Default was used as the optimisation level.

These optimisation passes consist of SROA, InstCombinePass, PromotePass,

LICM pass, reassociation pass, GVN pass, and simplify GVN pass.

These passes perform fundamental optimisations LLVM pass docs SROA (Scalar Replacement of Aggregates) promotes stack-allocated structures into SSA registers. That is, an allocation on the stack is hoisted up into global space so that the space is reused rather than reallocated every time. InstCombine simplifies instructions through algebraic transformations, while PromotePass elevates memory operations to register operations. LICM (Loop Invariant Code Motion) moves loop-independent code outside of loops by hoisting to preheaders or sinking to exit blocks. The reassociation pass reorders expressions to enable further optimisations. GVN (Global Value Numbering) eliminates redundant computations by identifying values that must be equal.

The community consensus appeared to be that -O2 should be used on it

and moved on. This means it is possible to do more tuning work on this.

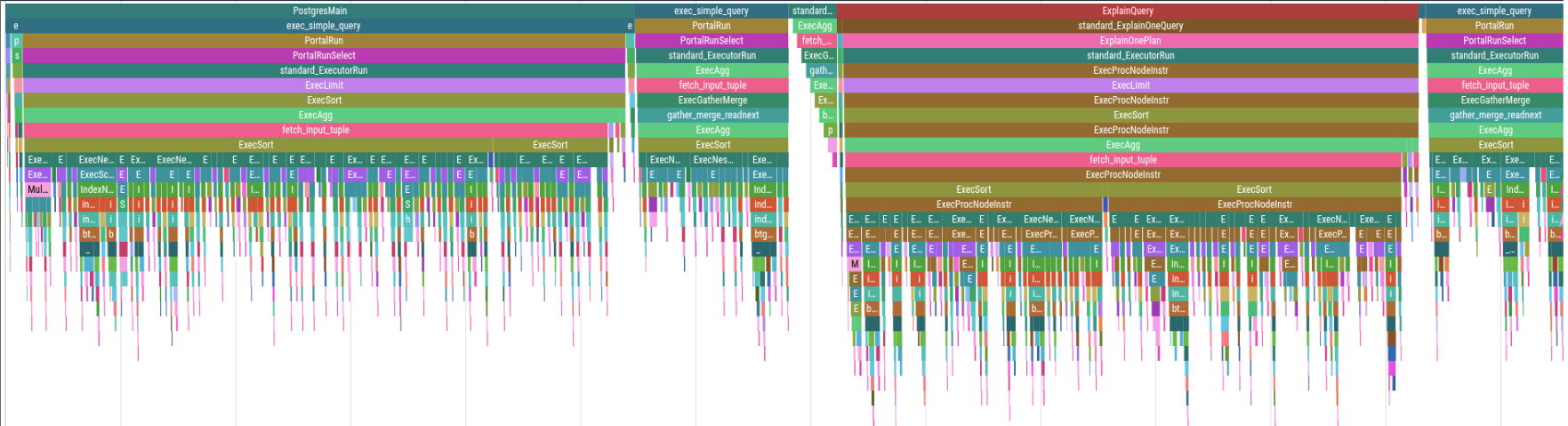

Profiling Support

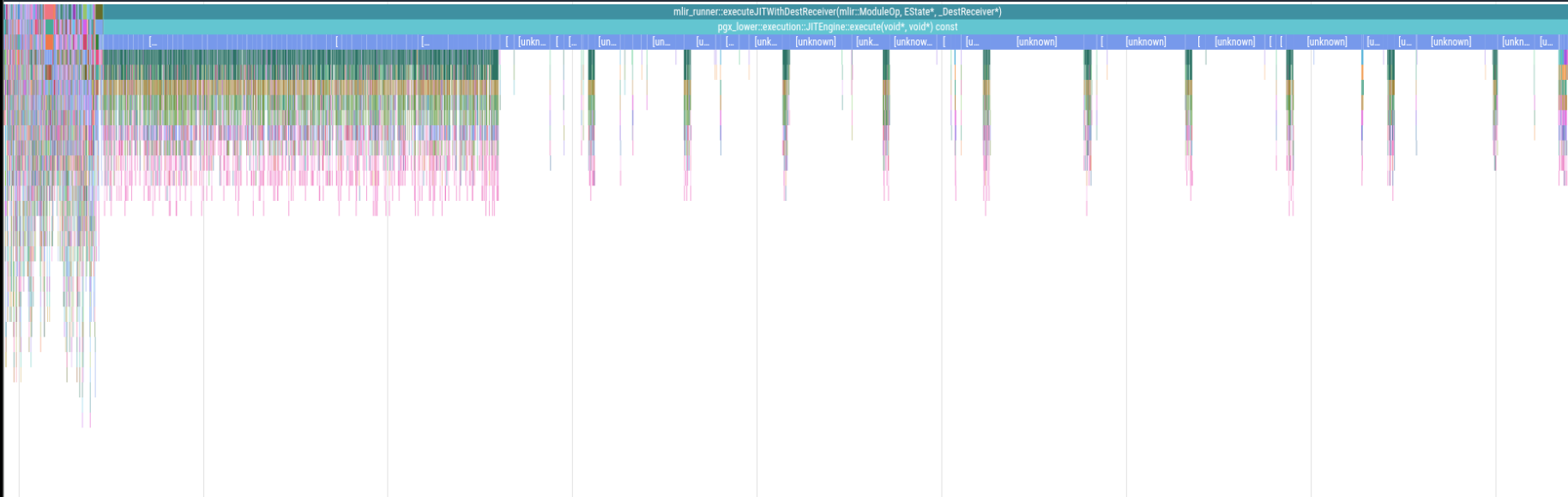

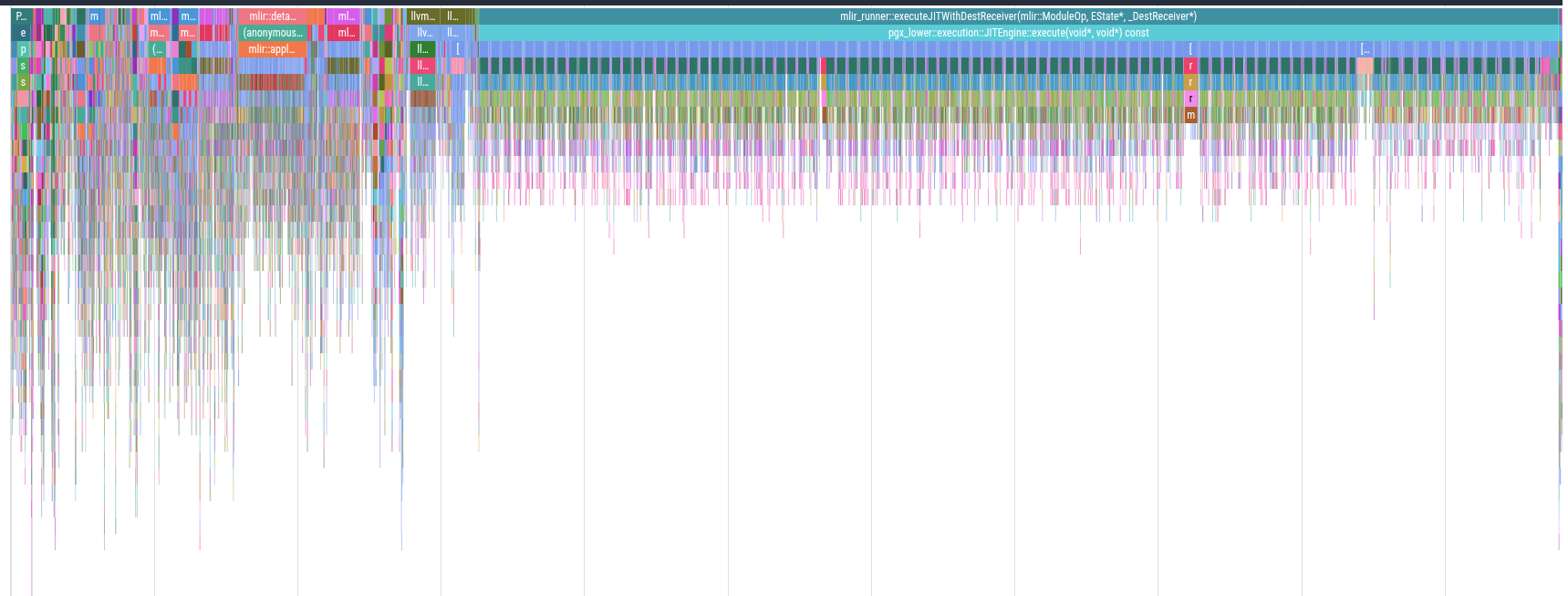

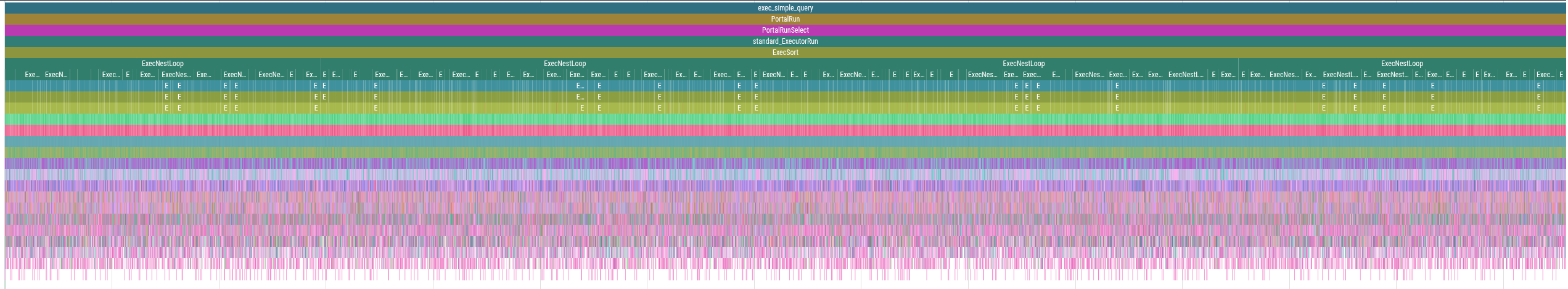

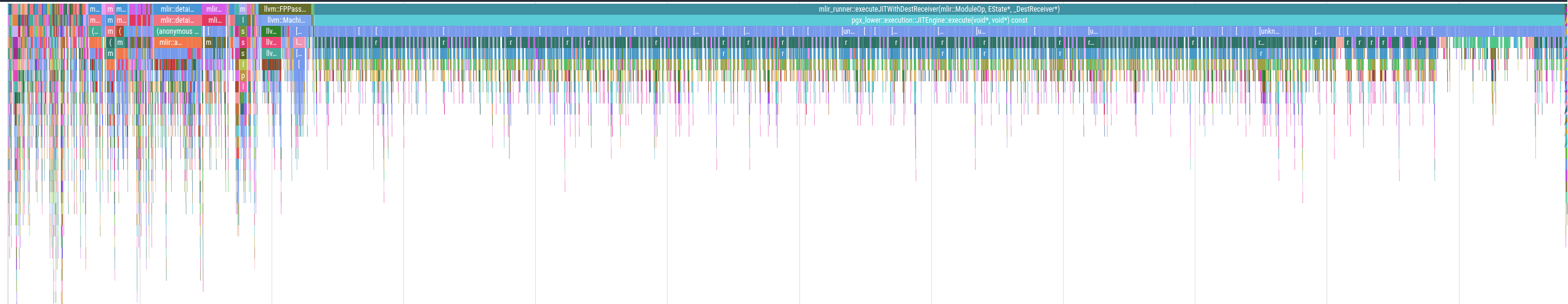

Code infrastructure was written to support magic-trace for profiling and isolating issues. A dedicated machine was configured for this purpose: an Intel i5-6500T with 16 GB of RAM and a Samsung MZVLB256HAHQ-000L7 NVMe disk. This was particularly useful for isolating obvious bottlenecks within the system and understanding the latency when compared to PostgreSQL. The profile represents a flame chart for query 3, and has a runtime of approximately 260 milliseconds. The functions that it calls are clear, and you can see how the query runs over time.

The flame chart before any optimisations were applied is visible in the performance profile. In that chart it is visible that too much time is spent inside the LLVM execution (those spikes in the last 2/3rds are table reads). After adjusting how tuples are read, ensuring joins go to the correct algorithm, introducing Postgres’s tuple-slot reading API, and disabling logs, the chart is improved. These optimizations improved the latency from 4.5 seconds to approximately 400 milliseconds.

The Benchmarking and Validation section outlines the specifics of running profiling jobs in a stable way.

Website

A small website was prepared so that users can interact with the lowerings and the compiler without installing the system themselves at pgx query site. Keep in mind that it relies on caching the results, it has a scale factor of 0.01 (10 MB of data), and the pgx-lower system there is (as of writing), running a debug build which has significantly longer runtimes. The implementation for this is at pgx-lower-addons repo. The implementation uses several technologies: Python for the backend server, SQLite for query caching, and React for the frontend. Docker containers support the reverse proxy with Nginx, while a private Grafana dashboard provides health monitoring.

Benchmarking and Validation

A challenge is that PostgreSQL contains a non-deterministic optimiser, and many small factors can affect runs. For this reason, a python script was created that reads from a YAML file, and does a benchmark run. This means we can specify runs beforehand, and run them robustly over a long period. Also, this benchmarking run computes a hash of the outputs between PostgreSQL and pgx-lower to validate the outputs are correct between all the runs, and the hashes were compared. This avoids storing large amounts of data over time, while issues can still be rediscovered in a large batch of runs.

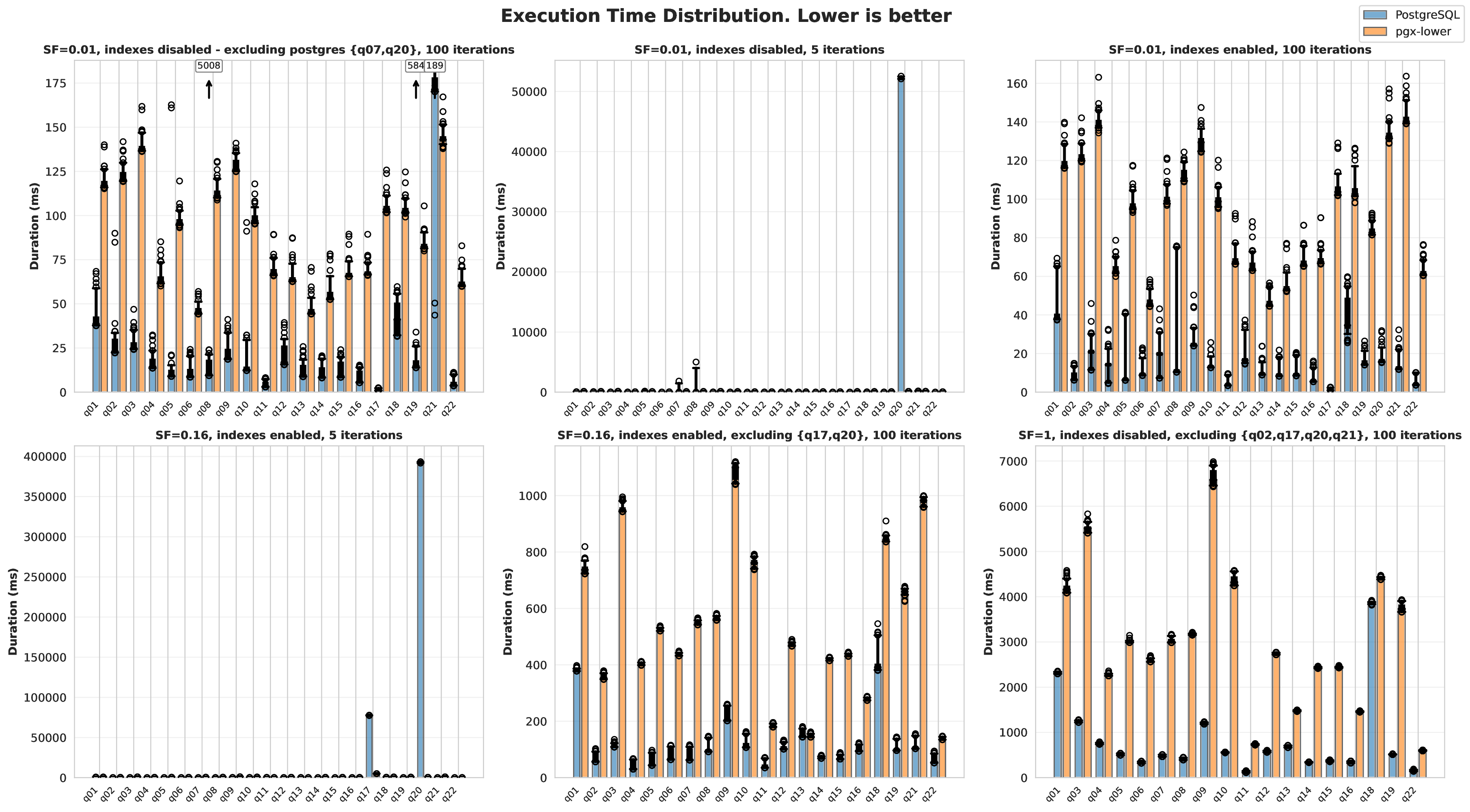

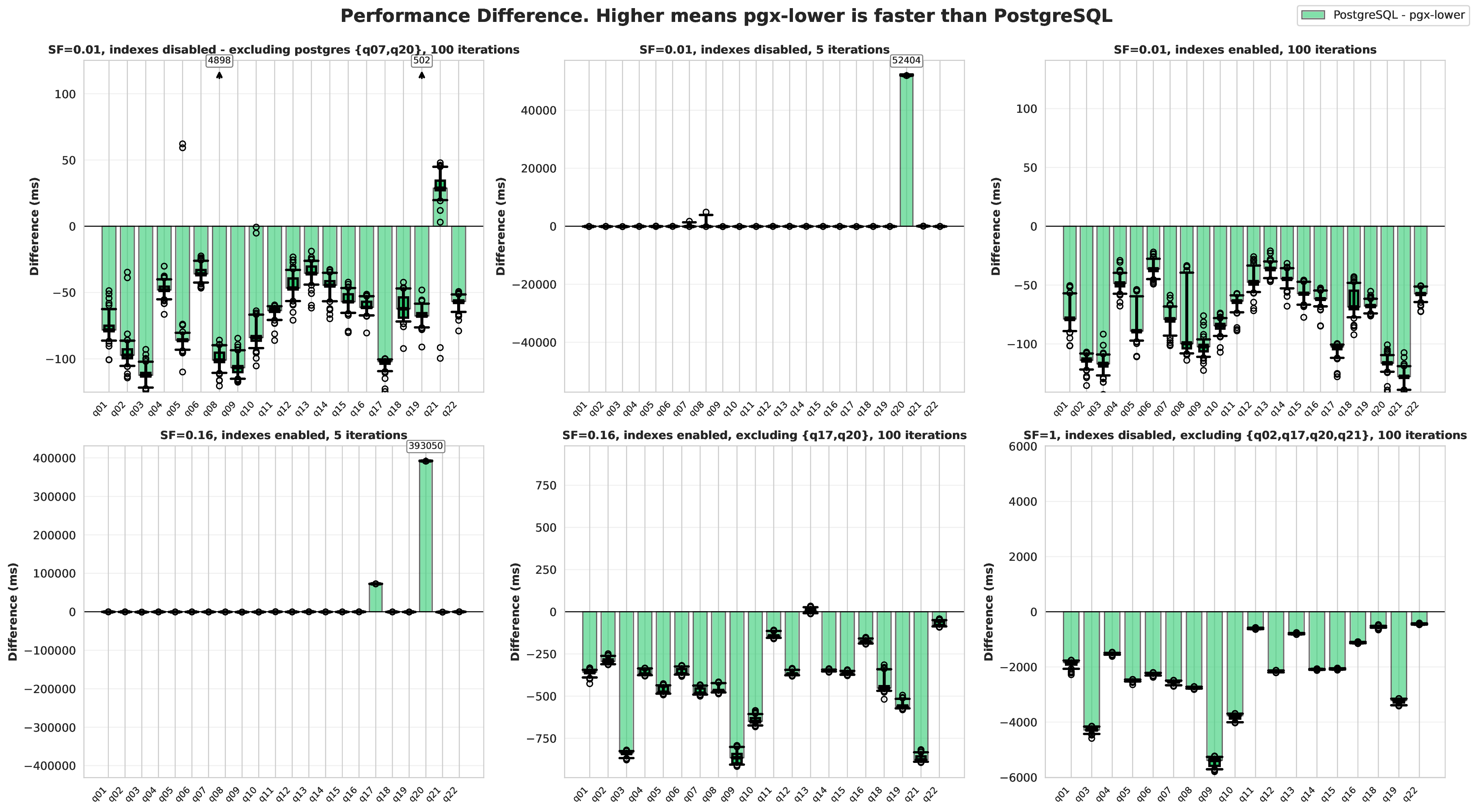

The benchmark configurations used are displayed in the configuration listing. These configurations allow testing across different scale factors, with and without indexes, and with varying iteration counts to understand performance characteristics. With multiple iterations, graphs that contain distributions can be created. These were decided by bucketing queries into small scale factor (0.01; 1 MB of data) to show the overhead cost of the JIT compiler, medium scale factor (0.16) to show how Postgres scales while still keeping all the queries enabled with indexes, and lastly scale factor 1 with the very time-consuming queries completely disabled. These disabled queries would take on the order of hours in PostgreSQL, so benchmarking them for multiple iterations was too time-consuming.

To disable indexes, cur.execute("SET enable_indexscan = off;") and

cur.execute("SET enable_bitmapscan = off;") were used in conjunction.

This means when the benchmarks say index scan is disabled, the bit map

scan is as well.

full:

runs:

- container: benchmark

scale_factor: 0.01

iterations: 5

profile: false

indexes: false

skipped_queries: ""

label: "SF=0.01, indexes disabled, 5 iterations"

- container: benchmark

scale_factor: 0.01

iterations: 100

profile: false

indexes: false

skipped_queries: "q07,q20"

label: "SF=0.01, indexes disabled - excluding postgres {q07,q20}, 100 iterations"

- container: benchmark

scale_factor: 0.01

iterations: 100

profile: false

indexes: true

skipped_queries: ""

label: "SF=0.01, indexes enabled, 100 iterations"

- container: benchmark

scale_factor: 0.16

iterations: 5

profile: false

indexes: true

skipped_queries: ""

label: "SF=0.16, indexes enabled, 5 iterations"

- container: benchmark

scale_factor: 0.16

iterations: 100

profile: false

indexes: true

skipped_queries: "q17,q20"

label: "SF=0.16, indexes enabled, excluding {q17,q20}, 100 iterations"

- container: benchmark

scale_factor: 1

iterations: 100

profile: false

indexes: false

skipped_queries: "q02,q17,q20,q21"

label: "SF=1, indexes disabled, excluding {q02,q17,q20,q21}, 100 iterations"The magic trace profiling also functions through this script, which is

what the profile tag there is for.

One thing to note here is that it was decided that only PostgreSQL and pgx-lower would be compared, rather than all the databases mentioned in The Related Work chapter. As showed that the impact of PostgreSQL’s architecture being on disk makes it significantly slower than any of the other databases.

Results and Discussion

Results

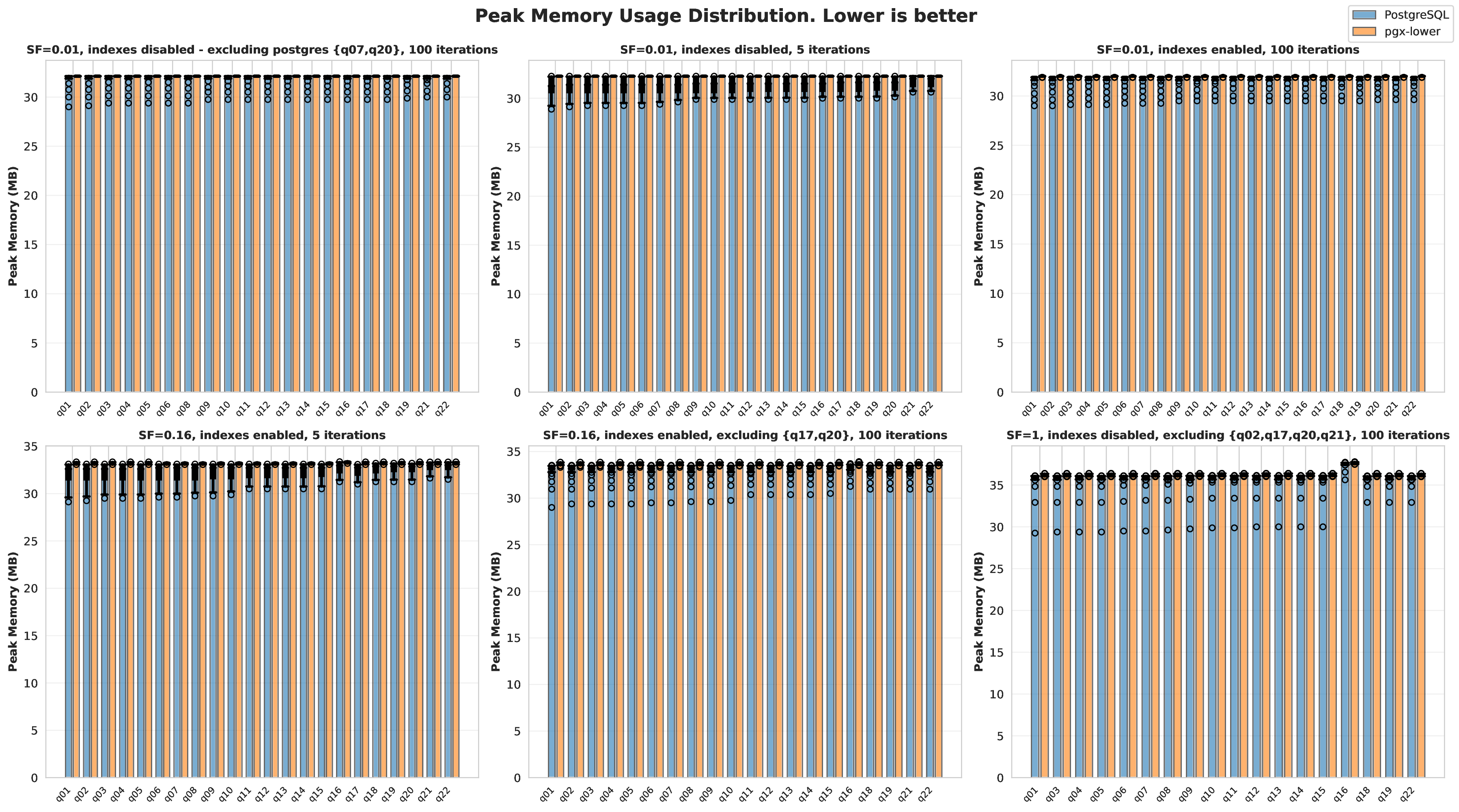

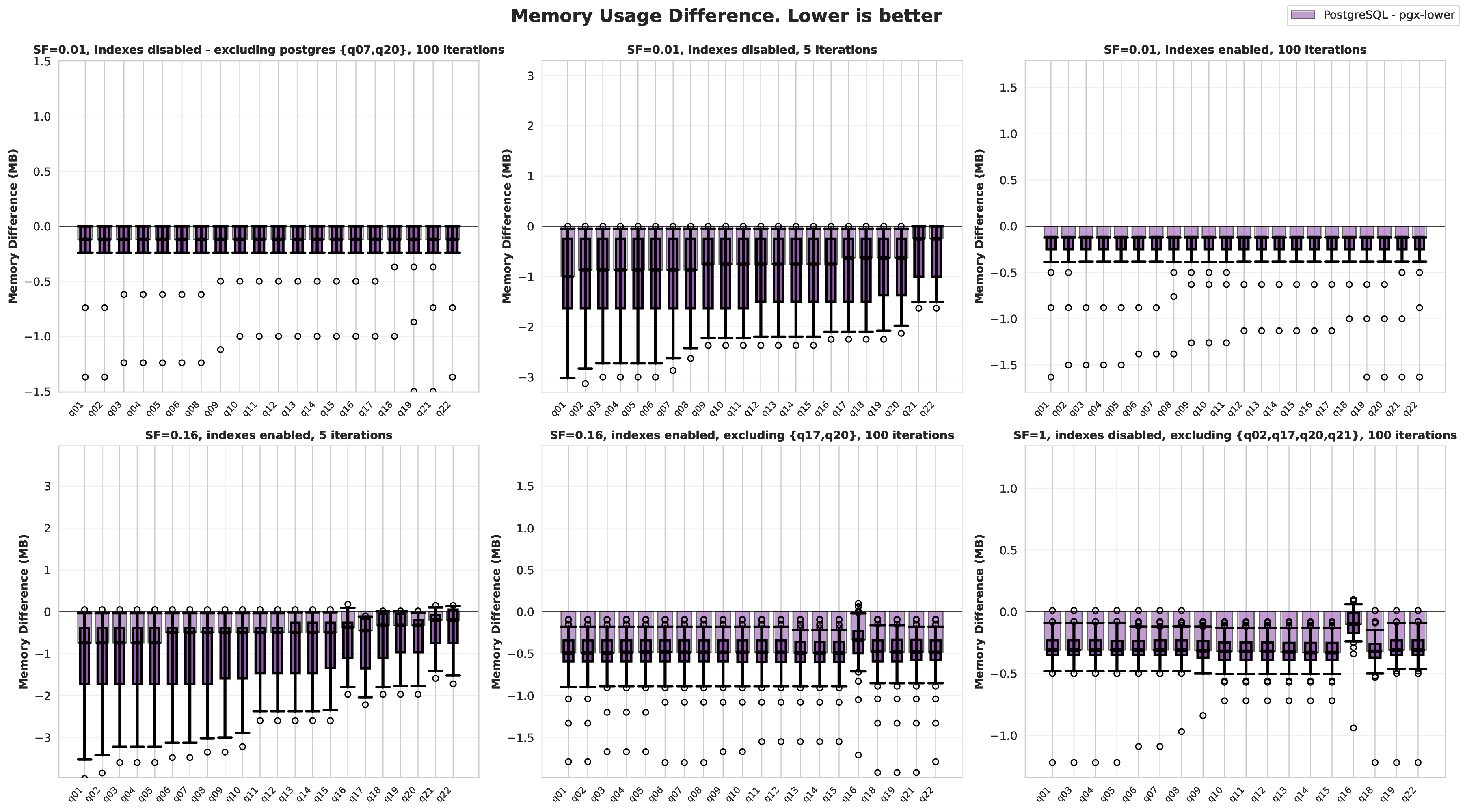

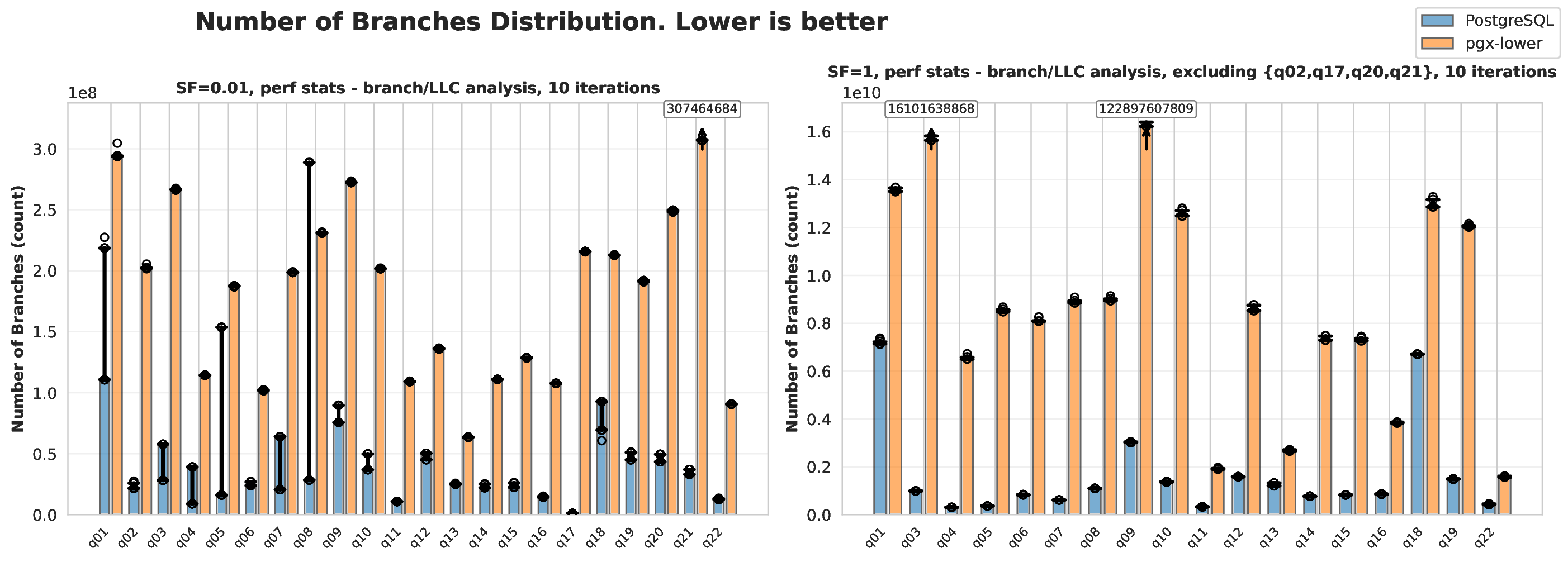

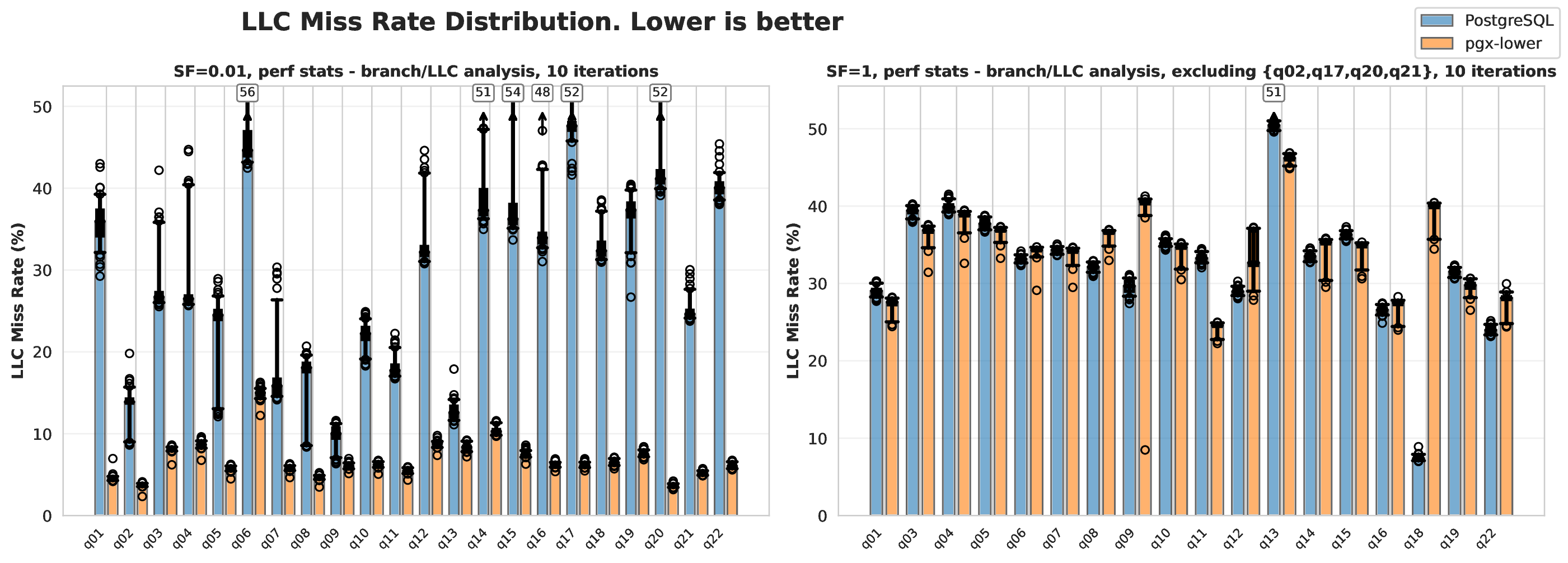

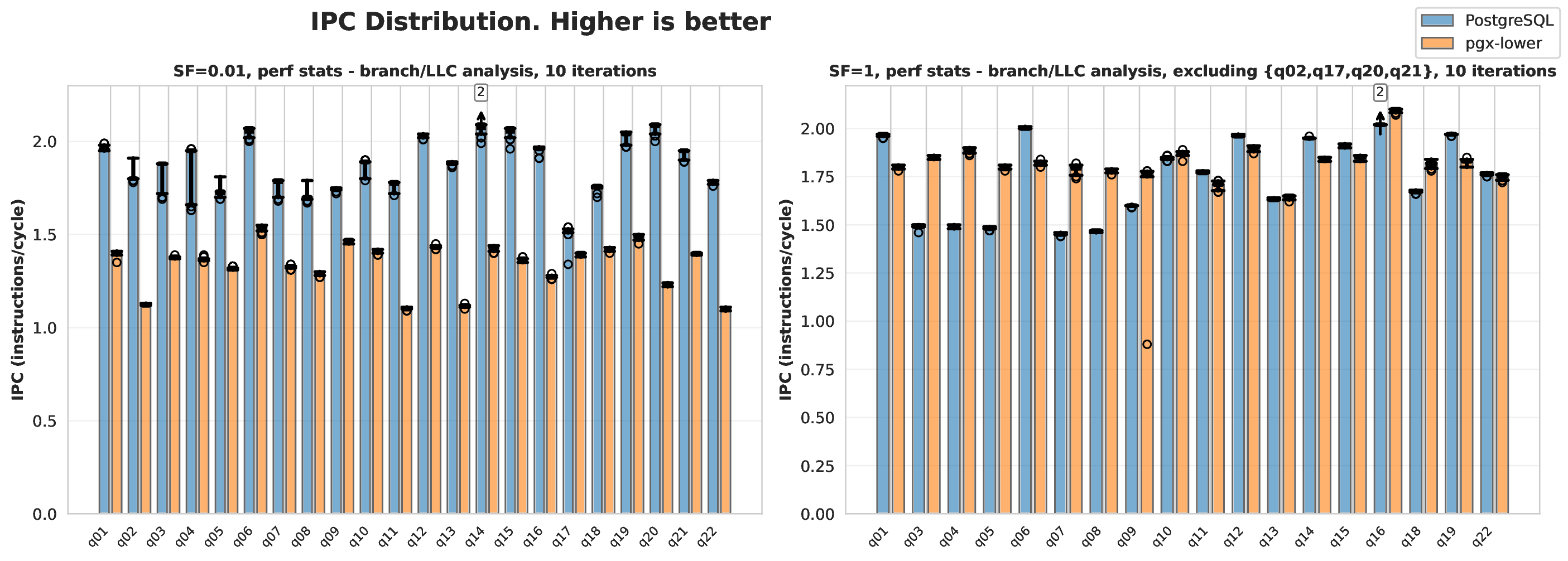

Results using the benchmarking and validation methodology described above are presented as follows. Box plots overlaid on graphs represent the 5th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 95th percentiles. Hollow circles mark outliers, and when inconvenient to display (as shown in the visualizations), arrows mark them instead. Matplotlib and Seaborn were used in Python to create all visualisations.

Another result worth mentioning is the integrated LingoDB code (including ./src/lingodb and ./include/lingodb) contains 13,875 lines of C++, while the pgx-lower section (./src/pgx-lower and ./include/pgx-lower) contains 12,324 lines of C++. This was measured with tokei commands, a command line utility for counting lines of code. In comparison, the official PostgreSQL executor is roughly 82,875 lines of code, and LingoDB is roughly 30,000 lines of code LingoDB MLIR paper PostgreSQL GitHub