Background

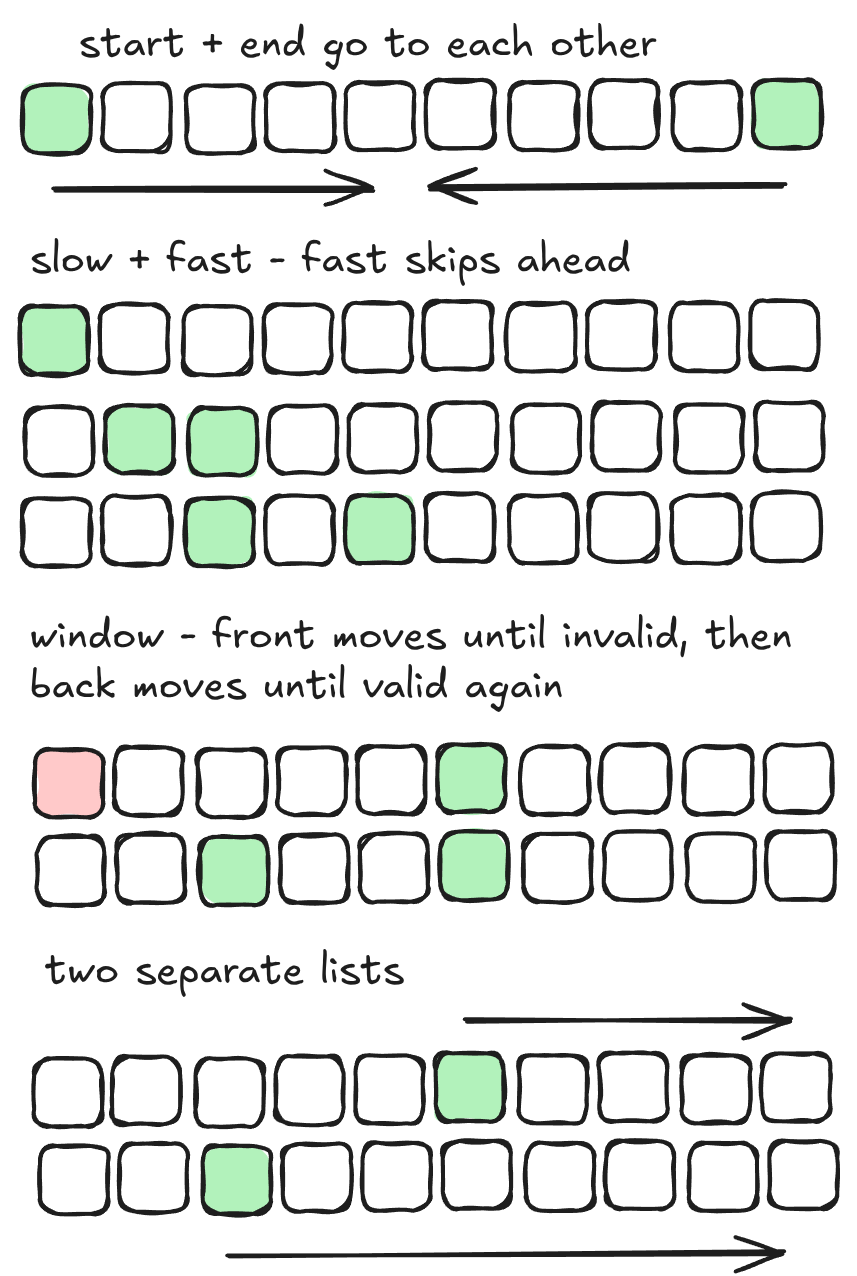

Broadly speaking, there are four primary two-pointer patterns: the start+end approach where the points converge, slow+fast where one skips ahead, sliding window where the front moves until it is invalid and pulls the back; and traversing two separate lists.

Conceptually, this is simple, but I’m writing this to cement the way I communicate about them.

Method

Start and End

Basics

We can apply this method when we either need to combine the two points, or we need to swap them. Every time we move we need to define whether we’re moving one or both of the points. I’ll be using start and end to annotate my variables here, but lo and hi, s and e, left, right, are also very common namings depending on the context. Probably left and right makes the most sense during an interview. If you use start and end, that can refer to the absolute start and end, but left and right still make enough sense. I can’t be bothered rewriting these chunks below.

Swapping or comparing can be done in palindrome problems or reversing problems, these are usually very trivial.

def reverse(word: str):

word = list(word) # strings are immutable, convert to list to make it fast

start, end = 0, len(word) - 1

while start < end:

word[start], word[end] = word[end], word[start]

start, end = start + 1, end - 1

return ''.join(word)

def is_palindrome(word: str):

start, end = 0, len(word) - 1

while start < end:

if word[start] != word[end]: return False

start, end = start + 1, end - 1

return TrueYou might notice that there is a more ‘concise’ way to write this:

def reverse(word: str) -> str:

word = list(word)

for i in range(len(word) // 2):

s, e = i, len(word) - i - 1

word[s], word[e] = word[e], word[s]

return ''.join(word)My problem with this is that with the -1 can introduce an off-by-one error. Your highest priority while writing code should be correctness and avoiding off-by-ones, so while that’s concise, I dislike it. Not to mention you can just use reversed(word)…

Okay, how about rule-based moving? In this kind of pattern move the appropriate pointer depending on some rule, or decide to skip points entirely while scanning to find valid ones. For instance, finding whether a string’s lowercase form with only alphanumeric values looks like this:

def is_alphanum_palindrome(word: str) -> bool:

start, end = 0, len(word) - 1

allowed = set(ascii_lowercase + digits)

while start < end:

if word[start].lower() not in allowed:

start += 1

continue

if word[end].lower() not in allowed:

end -= 1

continue

if word[start].lower() != word[end].lower():

return False

start, end = start + 1, end - 1

return TrueAnchors

Those are all trivial types of problems. Two-sum, where you find two numbers to sum to a problem, can be solved using start+end pointers and scales better into three-sum than the hash-map approach.

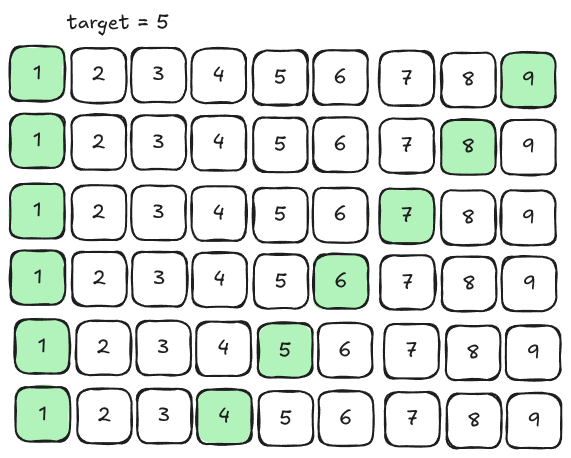

We sort the array of elements, then we shift down every loop that we’re unhappy because we want to change our value. The basic property in this solution is that our content is sorted, we have some target, and we can move greedily towards this target.

def two_sum(items: List[int], target: int) -> tuple[int, int]:

items.sort()

start, end = 0, len(items) - 1

while start < end:

total = items[start] + items[end]

if total == target:

return start, end

elif total < target:

start += 1

else:

end -= 1

return -1, -1

# or, if you need indexes

def two_sum_idx(items: List[int], target: int) -> tuple[int, int]:

items = [(x, i) for i, x in enumerate(items)]

items.sort()

start, end = 0, len(items) - 1

while start < end:

total = items[start][0] + items[end][0]

if total == target:

return items[start][1], items[end][1]

elif total < target:

start += 1

else:

end -= 1

return -1, -1Cool cool, we’re still in easy territory and we’ve defined some fundamental patterns. Mediums, like three-sum, are extensions of this. In more complex problems, you introduce anchors, your problem-space becomes multi-dimensional, or your conditional becomes more complicated. An anchor is when you iterate over the list, then do a two-pointer pattern on the remainder of the list. A potential complexity here is also that your conditional might changed as a result. Let’s say we have a two sum problem where we answer by the list of valid values, but we don’t permit duplicates:

def two_sum_values(items: List[int], target: int) -> list[tuple[int, int]]:

ans = []

items.sort()

start, end = 0, len(items) - 1

while start < end:

total = items[start] + items[end]

if total == target:

ans.append((items[start], items[end]))

start += 1

while start < end and items[start] == items[start - 1]:

start += 1

elif total < target:

start += 1

else:

end -= 1

return ansTo upgrade this we need to also ensure to avoid duplication on our anchor

def three_sum_values(items: List[int], target: int) -> list[tuple[int, int, int]]:

ans = []

items.sort()

for anchor in range(len(items)):

# extra to avoid duplication

if anchor > 0 and items[anchor] == items[anchor - 1]:

continue

start, end = anchor + 1, len(items) - 1

while start < end:

total = items[anchor] + items[start] + items[end]

if total == target:

ans.append((items[anchor], items[start], items[end]))

start += 1

while start < end and items[start] == items[start - 1]:

start += 1

elif total < target:

start += 1

else:

end -= 1

return ansAdding Complexity / Multi dimensionality

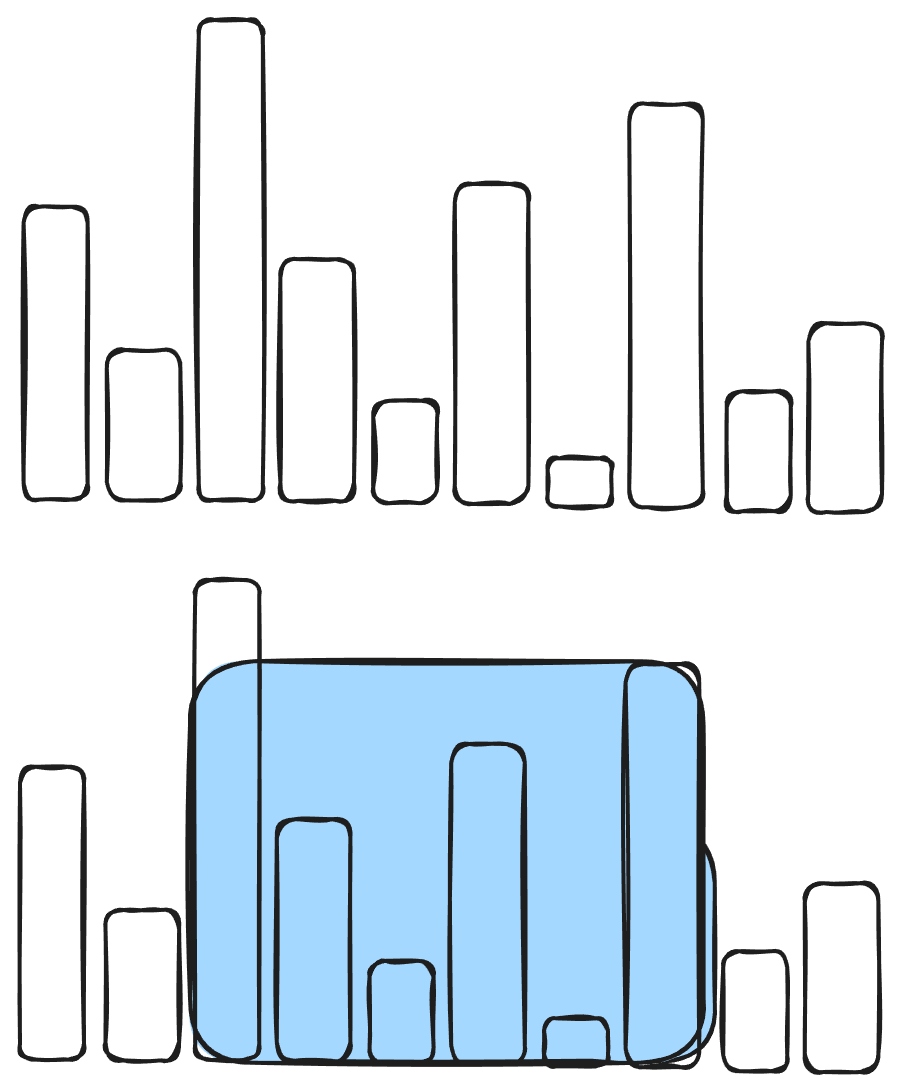

An example of a problem where there’s an increase in complexity is something like a maximum water problem. For this, the difficulty lies in realising the greedy conditional. However, the code itself is quite straightforward.

First image is a set of pillars, then you want to find the largest rectangle between two pillars by its

Looking at this, it’s hard to immediately declare that putting two pointers on each side and moving one at a time can always increase the volume. We aren’t progressively increasing the volume or sorting it, but we only need the largest rectangle.

def largest_rectangle(heights: List[int]) -> int:

start, end = 0, len(heights) - 1

best = 0

while start < end:

best = max(best, (end - start) * min(heights[start], heights[end]))

if heights[start] < heights[end]:

start += 1

else:

end -= 1

return bestYou can also accumulate this pattern by adding the rectangles as you go

def all_sizes(heights: List[int]) -> int:

start, end = 0, len(heights) - 1

tallest = 0

total = 0

while start < end:

cur = min(heights[start], heights[end])

if cur > tallest:

diff = cur - tallest

total += diff * (end - start + 1)

tallest = cur

if heights[start] < heights[end]:

start += 1

else:

end -= 1

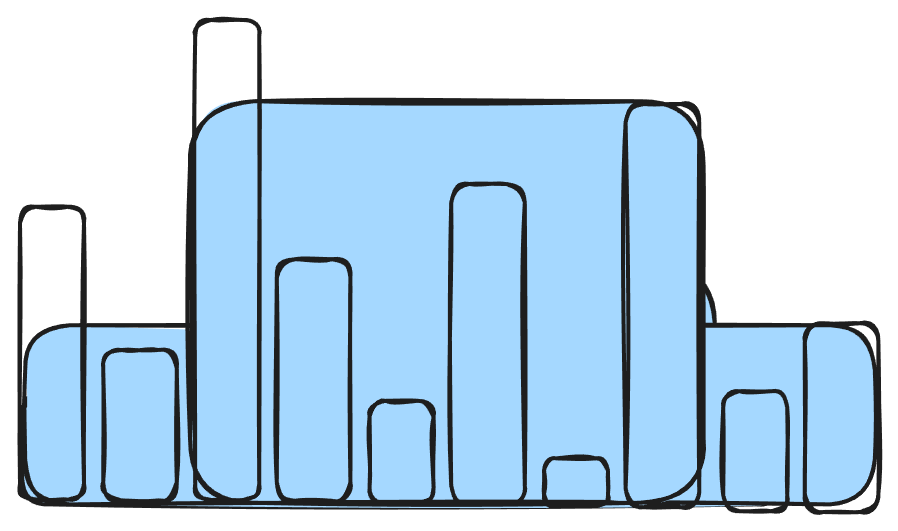

return totalCongratulations, we formed the foundation for a hard-level question. However, the hard excludes the height of the pillars. You also can’t subtract the height of the pillars because of peaks. Go look at that last image, two of the pillars are peaking out of the volumes, so we need to account for that by making sure we do not subtract that part of the height.

class Solution:

def trap(self, heights: List[int]) -> int:

start, end = 0, len(heights) - 1

tallest = 0

total = 0

while start < end:

cur = min(heights[start], heights[end])

if cur > tallest:

diff = cur - tallest

total += diff * (end - start + 1)

tallest = cur

if heights[start] < heights[end]:

heights[start] = min(heights[start], tallest)

start += 1

else:

heights[end] = min(heights[end], tallest)

end -= 1

heights[start] = min(heights[start], tallest)

heights[end] = min(heights[end], tallest)

return total - sum(heights)Even though we incrementally built up to that solution, it’s far from the best approach for accumulation. Accumulation is a common enough pattern that it’s something you should just “know”. This approach instead does vertical slices

class Solution:

def trap(self, heights: List[int]) -> int:

start, end = 0, len(heights) - 1

max_start, max_end = 0, 0

total = 0

while start < end:

if heights[start] < heights[end]:

max_start = max(heights[start], max_start)

total += max(0, max_start - heights[start])

start += 1

else:

max_end = max(heights[end], max_end)

total += max(0, max_end - heights[end])

end -= 1

return totalThree-pointer partition

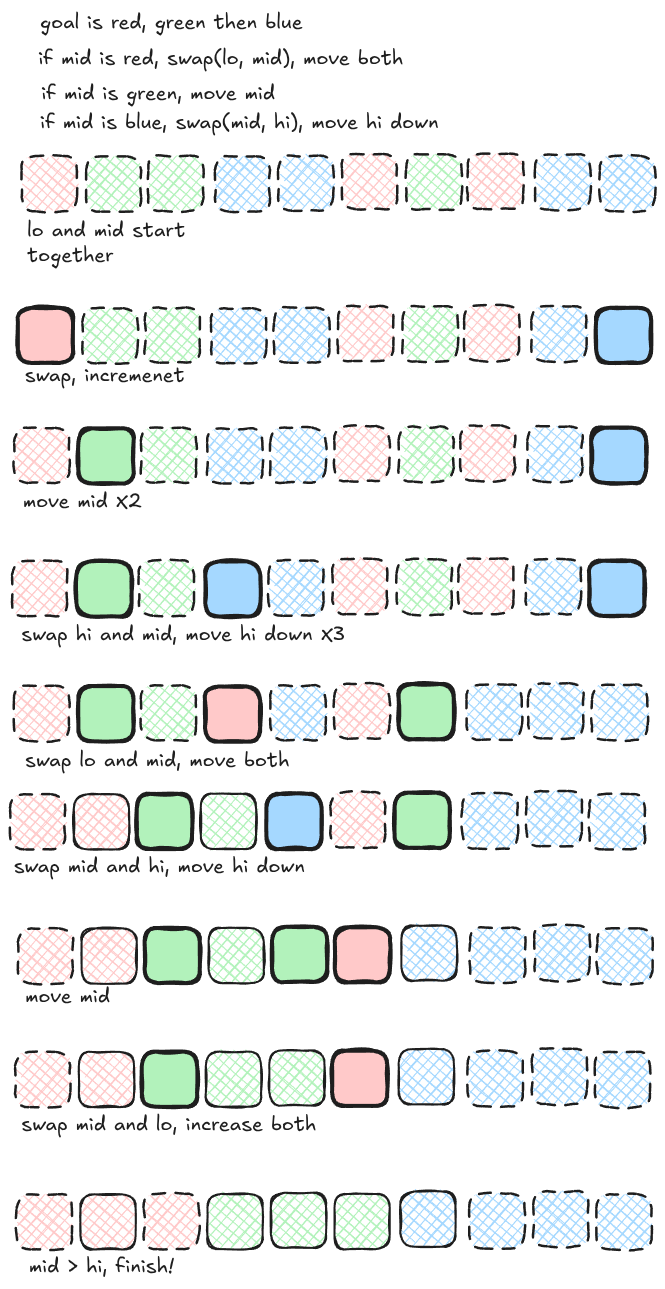

In this version, a mid-point is introduced and your goal is to partition your list into three chunks. This is also know as the dutch national flag problem. Your scanning is driven by the mid pointer, and then you swap the other values around based on this mid pointer.

def sort_colours(nums: List[int]) -> None:

lo, mid, hi = 0, 0, len(nums) - 1

while mid <= hi:

if nums[mid] == 0:

nums[lo], nums[mid] = nums[mid], nums[lo]

lo += 1

mid += 1

elif nums[mid] == 1:

mid += 1

else:

nums[hi], nums[mid] = nums[mid], nums[hi]

hi -= 1In my opinion, this kind of problem is too obscure to be useful.

Inside-out

This isn’t really a start+end two-pointer problem anymore, but it is closely related. Rather than two pointers moving in towards each other, you make them move away. The classic longest palindrome inside a list problem uses this:

def longest_palindrome(s: str) -> str:

res = ""

def expand(l, r):

# Move pointers outwards while valid

while l >= 0 and r < len(s) and s[l] == s[r]:

l -= 1

r += 1

return s[l + 1 : r]

for i in range(len(s)):

odd = expand(i, i)

if len(odd) > len(res): res = odd

even = expand(i, i + 1)

if len(even) > len(res): res = even

return resThere is also a faster approach to the longest palindrome problem, but this is usually good enough.

Fast and Slow

Fast and slow is also commonly called tortoise and hare or Floyd’s Tortoise and Hare Cycle Detection source. This type of problem is usually in the context of linked lists or graphs to find cycles. Again, it’s simple conceptually: you start your two pointers in the same spot, then you move the slow one a step at a time, and the fast one at two steps. When they collide you have a cycle!

def cycle(head: ListNode) -> bool:

slow, fast = head, head

while fast and fast.next:

slow = slow.next

fast = fast.next.next

if slow == fast:

return True

return FalseThis can also be used to find the middle of a linked list:

def middle(head: ListNode) -> ListNode:

slow, fast = head, head

while fast and fast.next:

slow = slow.next

fast = fast.next.next

return slowSometimes you specifically want the beginning of the cycle:

def detect_cycle_start(head: ListNode) -> ListNode | None:

slow, fast = head, head

while fast and fast.next:

slow = slow.next

fast = fast.next.next

if slow == fast:

break

else:

return None

# Reset slow to head. Move both at 1x speed.

slow = head

while slow != fast:

slow = slow.next

fast = fast.next

return slowWhen typing this it is vital to remember both of fast and fast.next in your while loop. A common off-by-one is to just do slow and fast.next, but this can give you null pointer issues.

These are usually elevated in difficulty by putting them into graphs, cyclic sorts, unintuitive situations, or dynamic rules. Graphs need you to iterate over neighbours as well. Cyclic sorts deserves an article of its own, but for instance, find duplicates is solveable with a cyclic sort and a slow-fast pointer pattern. Unintuitive situations (like finding duplicates) and dynamic rules can be difficult just to realise the algorithm, but simple to implement.

Sliding Window

Sliding window is an extremely extendable problem with three core types of patterns. In the first type, you slide the front forwards until you enter some defined ‘invalid state’, and then you drag the back until you’re valid again, and continue. In the second, when you enter this invalid state you reset by immediately bringing the back pointer all the way up.

def longest_non_duplicate(arr: List[int]) -> int:

lo = 0

best = 0

seen = defaultdict(int)

for hi in range(len(arr)):

seen[arr[hi]] += 1

while seen[arr[hi]] > 1:

seen[arr[lo]] -= 1

lo += 1

best = max(hi - lo + 1, best)

return best

def max_subarray(arr: List[int]) -> int:

curr = 0

best = 0

for v in arr:

curr += v

best = max(curr, best)

if curr < 0: curr = 0

return bestIn the last pattern, you need to initialise a fixed-size window then slide it along.

def max_value(arr: List[int], sz: int) -> int:

total = 0

n = len(arr)

for i in range(min(n, sz)):

total += arr[i]

best = total

for i in range(min(n, sz), n):

total = total + arr[i] - arr[i - sz]

best = max(best, total)

return bestThe more difficult sliding-window problems add complexity to this, or introduce faster ways for you to drag the back. These usually involve introducing another data structure into the mix. For instance, you need to return the minimum length of a sub-array whose sum is greater than or equal to the target. You need to create a prefix sum, then binary search backwards.

def min_length_subarray(nums: List[int], target: int) -> int:

n = len(nums)

if n == 0: return 0

sums = [0] * (n + 1)

for i in range(n):

sums[i + 1] = sums[i] + nums[i]

min_len = float('inf')

for i in range(1, n + 1):

to_find = sums[i] - target

left_idx = bisect_right(sums, to_find)

if left_idx > 0:

current_len = i - (left_idx - 1)

min_len = min(min_len, current_len)

return min_len if min_len != float('inf') else 0You could argue this isn’t a sliding window problem anymore though, and rather a prefix sum problem.

Another common pattern is a monotonic queue approach to find a maximum in a sliding window. For instance, given a list of numbers, find the maximum number within each window. You create a deque that’s going to contain indices of decreasing numbers inside of your window. For each number, you should pop the back of the queue until the back is bigger than your current number, and append it. This lets you find the maximum within each window in .

def max_sliding_window(nums: List[int], k: int) -> List[int]:

q = deque()

ans = []

for i, curr in enumerate(nums):

# pop anything out the back that's smaller than the new number

while q and nums[q[-1]] <= curr:

q.pop()

q.append(i)

# pop if it's out of the bounds of the window

if q[0] == i - k:

q.popleft()

# put it into the answer if we're at least a window in

if i >= k - 1:

ans.append(nums[q[0]])

return ansAnother trick is in counting problems. For instance, let’s say we’re given a list and we want to count the number of sub-arrays with exactly distinct characters. Doing this in brute force would be because you need to count the distinct characters in each possible window. Instead, you can count the number of “at most” K distinct numbers, then subtract at_most(arr, k) - at_most(arr, k - 1) to find exact instead. This way, you can transform “exact” problems into “at most” ones, then solve the exact ones using that.

For this problem, you can count until you have less than or equal to distinct characters in your window, then count the length of the window because it contains every sub-array with at most distinct numbers.

def subarrays_with_k_distinct(arr: List[int], k: int) -> int:

return at_most(arr, k) - at_most(arr, k - 1)

def at_most(arr: List[int], k: int) -> int:

count = defaultdict(int)

left, distinct, ans = 0, 0, 0

for right in range(len(arr)):

# count as distinct if it's new

if count[arr[right]] == 0:

distinct += 1

count[arr[right]] += 1

# if we have too many, shrink our window

while distinct > k:

count[arr[left]] -= 1

if count[arr[left]] == 0:

distinct -= 1

left += 1

# the number of valid arrays is the length of the window

ans += right - left + 1

return ansThese problems can also become multi-dimensional, such as this IOI problem, but these are usually a 1D sliding window while iterating over the other dimension. Not something where you have two sliding windows and you shrink both of them in the same problem space.

It is also worth mentioning that the hash map pattern from the start can become much more complex, such as a ‘minimum window sub-string’ or a ‘find all anagrams’ style problem. Your hash map starts containing sub arrays of the large array.

Two separate lists

This is a generic pattern, where instead of your two pointers existing inside the same list you put them into two different lists. In theory you can do all of the previous patterns inside of this, but it usually is not that complicated. The classic example of this is merge two sorted linked lists:

def merge(head1: ListNode, head2: ListNode) -> ListNode:

dummy = ListNode()

cur = dummy

while head1 and head2:

if head1.val < head2.val:

cur.next = head1

head1 = head1.next

else:

cur.next = head2

head2 = head2.next

cur = cur.next

if head1: cur.next = head1

if head2: cur.next = head2

return dummy.nextSimilar to this, you can do something where you extract a ‘closest’ to some target pair. As long as you have logic for when to move one value forwards over the other, you can use this pattern:

def closest_pair(list1: List[int], list2: List[int]) -> int:

list1.sort()

list2.sort()

p1, p2 = 0, 0

n, m = len(list1), len(list2)

best, best_value = (-1, -1), float('inf')

while p1 < n and p2 < m:

diff = abs(list1[p1] - list2[p2])

if diff < best_value:

best = p1, p2

best_value = diff

if diff == 0: return 0

if list1[p1] < list2[p2]:

p1 += 1

else:

p2 += 1

return best_valueAnother application of this pattern is sub-sequencing. You’re crossing off that the shorter list is a sub-sequence of the larger one:

def subseq(longer: List[int], shorter: List[int]) -> bool:

if not shorter: return True

l_i, s_i = 0, 0

while l_i < len(longer):

if shorter[s_i] == longer[l_i]:

s_i += 1

if s_i == len(shorter):

return True

l_i += 1

return FalseConclusion

In this article we’ve broadly covered the patterns of two-pointer problems. This included start and end pointers, fast and slow, sliding window and two separate lists. In reality, you can put two coordinates inside any problem space and arbitrarily move them to solve problems. However, this should form a basis for approaches to take. These should be quite useful for greedy patterns and discovering cycles.

zyros

zyros