Background

This page aims to answer what “going above and beyond” in your job as a software engineer looks like. Similarly, how to stand out in an internship, survive probation, or contribute to a good engineering team culture. I’ve primarily worked as a back-end developer, so what I say here might not be completely applicable to front-end developers or researchers. Most likely, those will have extra nice-to-haves, like A/B tests.

Method

Onboarding documentation

So, you’ve joined a team as an intern or full-timer. Does your team have a centralised onboarding document for new hires? No? This is a low-hanging fruit that yields a massive amount of credit! It shows that you’ve learned and understood some business context, the wider team, and you can sign this off as “multiplicative” impact quite easily.

The other type of documentation you can make is how-to’s; such as how to update the database, make message structs, or dashboards. Depending on your organisation, these probably already exist somewhere or else they’ll be very short-lived. You can write these whenever, but they might not be as long-lasting or impactful.

If you write or update this onboarding documentation, you should do it roughly 2-3 months into your role. Your goal here is to consolidate everything you’ve gone through and include a description of your team’s goals. Somebody new should be able to read this with no other context, and have most of their questions answered.

- About the document: What this document is, people should copy this document and make a personal version so they can edit it. They can update the base one too.

- People should fill in their start date and who their mentor or manager is.

- Where the team exists in the broader company, and a graph/picture of this.

- What the subteams are within your team, and what the goal is as a team.

- How the company’s teams are structured (qa, fe, be, data, product managers).

- Any video content people have made that introduces the team.

- When is standup, technology sharings, other regular meetings, whether they’re important to attend and why.

- Important people for relevant teams.

- Week-by-week checklist, saying hello to everyone, list of onboarding documents, links to all the group chats, links to the internal platforms and any relevant documentation

- List of all the important codebases and platforms for managing code. Label which subteams these belong to, and what the codebase does.

- Summary of core services the team uses like RDS, what they are, how to find them.

- Guide about company benefits and human-resources things.

- Frequently asked questions.

- More document links.

What goes into this list will be heavily company-dependent. For a startup, a lot of this might not exist and depending on their hiring rates it might not be useful at all.

First Project, or, Service addons

Let’s say you’ve finished making your intern project, your first major feature, or just some feature. This is an important moment. Managers and coworkers tend to watch your first output quite closely because it establishes the bar about your outputs. The only thing they really know about your work is your interview performance and stories, or maybe you’ve fixed a couple of smaller bugs.

Your goal should be to increase the visibility of what your feature is, how it works, and how well it accomplished your goal. This makes things much easier for coworkers that need to use your feature or understand it. Some of this might not be your responsibility to make, such as the how-to document might need to be written by a product manager.

- Have a document for what the feature is, from a user’s perspective. This should include expected benefits for your feature, and be non-technical.

- Write metrics from your service into a database.

- Create a dashboard from those metrics.

- Make sure you have trace logging and your logging is reasonable.

- Set up in a chat to ping you if the service goes down or becomes unhealthy.

- Automate the feature’s schedule. For instance, if the feature clones databases you should make sure it automatically happens without manual intervention. If it isn’t automated, it’ll be forgotten and become useless.

- Do a stress test on the feature, and highlight what’s the bottleneck. Ideally this comes with a flame chart.

- Have a separate document for what the feature is internally. This should answer technical questions

- Which codebase is it in, or where in the codebase is it?

- What services did you use and why did you pick them, such as a Lambda or K8s cluster?

- What data are you persisting? What API secrets did this need?

- Did you have to check with compliance or legal?

- The metrics and dashboards for the feature.

- Screenshots of the stress tests.

- And tell people about it!

Some of these things will require you to learn your company’s internal platform, which can be difficult if nobody is around to explain it to you. If you’re lucky someone else will have time for this, but otherwise you’ll have to go through it.

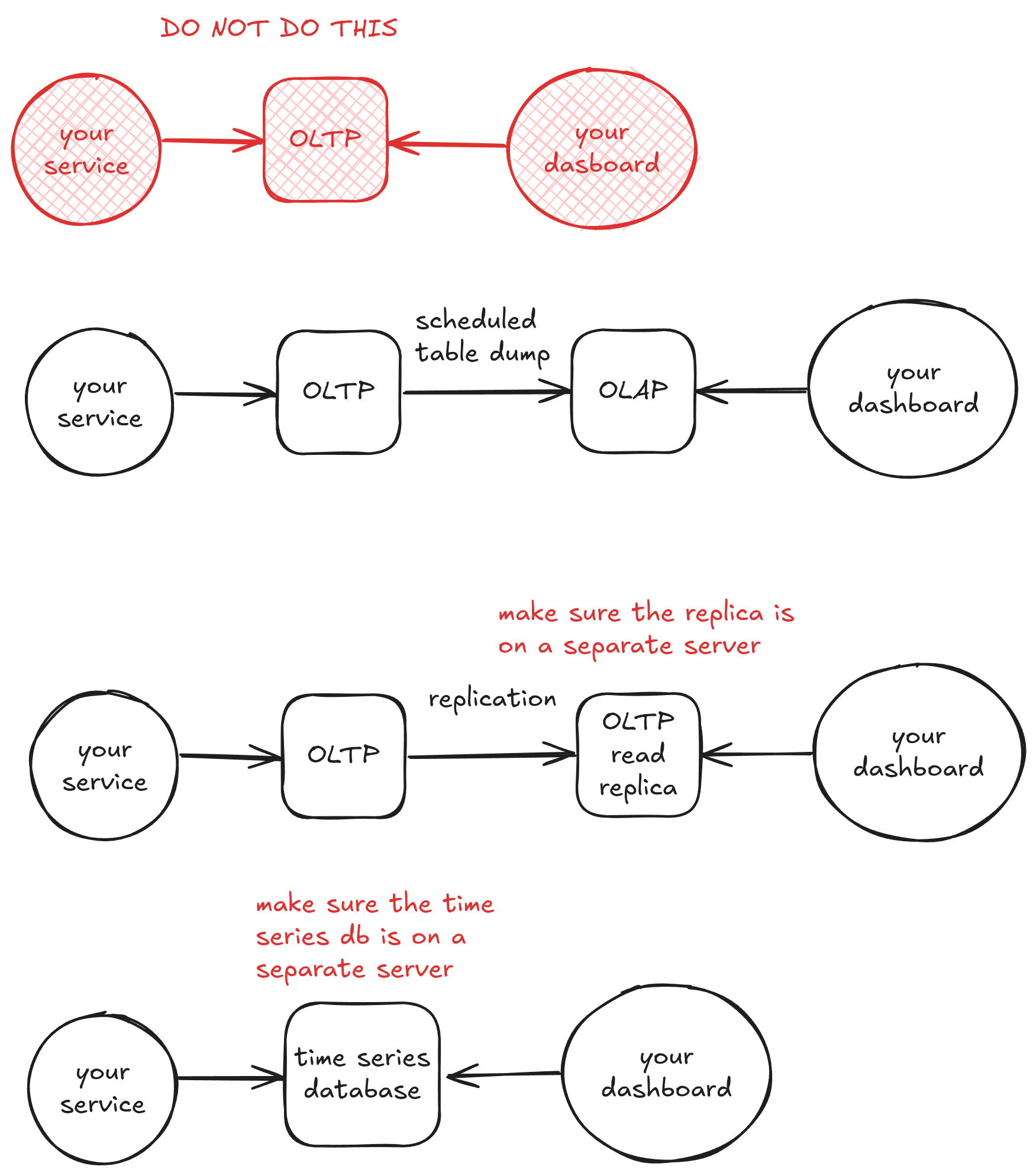

If you’re the first person to make metrics or a dashboard you should be careful. It’s quite common for teams to have nothing. You’re going to have to learn the difference between OLTP, OLAP and time series databases and their purposes.

OLTP stands for online transactional processing, OLAP is online analytical processing, and a time series database has strong support for time searches. Typically, you attach an OLTP database (i.e. MySQL) to your live service. It’ll handle many concurrent requests and do key-value lookups for you. OLAP will only run a small number of queries at a time and be good at aggregation operations.

A dashboard can be really heavy weight to open up. It sounds goofy, but in my career I’ve had six instances where our service went down for some period because of bad metrics collection. We used a time series database, InfluxDB, that sat on the same server as our core service. InfluxDB is an in-memory database, so when someone opens the dashboard it takes all the data into RAM, crippling the entire service! Do not do that! This is also possible with an OLTP databases. Make sure your metrics are read from a separate server!

Culture

I find that most people don’t think about or respect company culture values. Nobody really thinks about them unless you’re talking to some upper management and they need to justify things or review coworkers. It seems the goal is more for upper management to have a framework to handle conflicts, rather than ‘embodying’ it every day. I think this is still an ~okay use of the values.

The issue is very commonly they contradict each other, or they’re just clownery. Almost every company’s values is a copy of Amazon’s leadership principles. ‘Bias for action’ vs ‘deep dive’, or ‘bias for action’ vs ‘insisting on the highest standards’, or ‘frugality’ vs ‘think big’, ‘have backbone and disagree’ vs ‘commit and earn trust’. There are a lot of contradictions, and are you really going to lecture adults about how they need to ‘insist on the highest standards’? I understand having a framework to point at when dealing with cultural issues is important, though.

That being said, being blame-free and allowing stupid questions without criticism is critical. If I’m new and I ask you a stupid question, then you call me an idiot, I’ll stop asking you questions. So now I might not have anyone to ask questions anymore. If someone asks me why I didn’t do something, I’ll respond that I don’t have anyone that’s willing to answer questions and recount our interaction to management. Furthermore, if blame gets assigned to people, people will just avoid working on important things. It usually isn’t worth the effort to fix either of these things if you’re in a situation like this. If a senior person says your question is stupid, then you complain to management, that person won’t want to work with you at all anymore.

Pull Requests

When it comes to pull requests, it will be completely team dependent and who you’re working with. As AI tooling becomes more popular, I’ve generally noticed that less and less product teams seem to have a strong pull request culture. Your pull requests aren’t just 200 lines anymore, they’re 2,000 lines. Maybe someone enabled AI unit test generation, so your 2,000 line pull request blows up to 20,000 lines! With AI tooling like this and management pushing people, it isn’t surprising the pull request review culture melts away.

Even if your team has a habit of rubber stamping (approving without reading), you should still raise pull requests and write detailed descriptions on them.

If someone sends you a pull request, review it! Ask questions! If you’re new, your main takeaway should be more learning how to do things. Usually people don’t send pull requests to the intern for a review, they send them so the intern reads through and learns. However do not click ‘Merge’ after you approve. Pull request etiquette is you send the pull request to someone, they approve it, then you press merge.

Conclusion

We’ve gone over writing onboarding documentation, writing documentation, what addons to make for completed services, what ‘culture’ is and the nature of pull requests. There is a lot more of additional things to software engineering, but this should give you a reasonable basis of extra things you should be doing on top of just writing code.

zyros

zyros