Background

Monotonic stacks are when your solution involves maintaining a stack or queue that remains strictly sorted. Usually this means if you hit a number bigger than your tail, you either drop the number, or pop until you can insert it. These are difficult. The thing is your problem is usually a greedy one, so you need to identify the greedy pattern, and then how to do it with a monotonic stack on top of this.

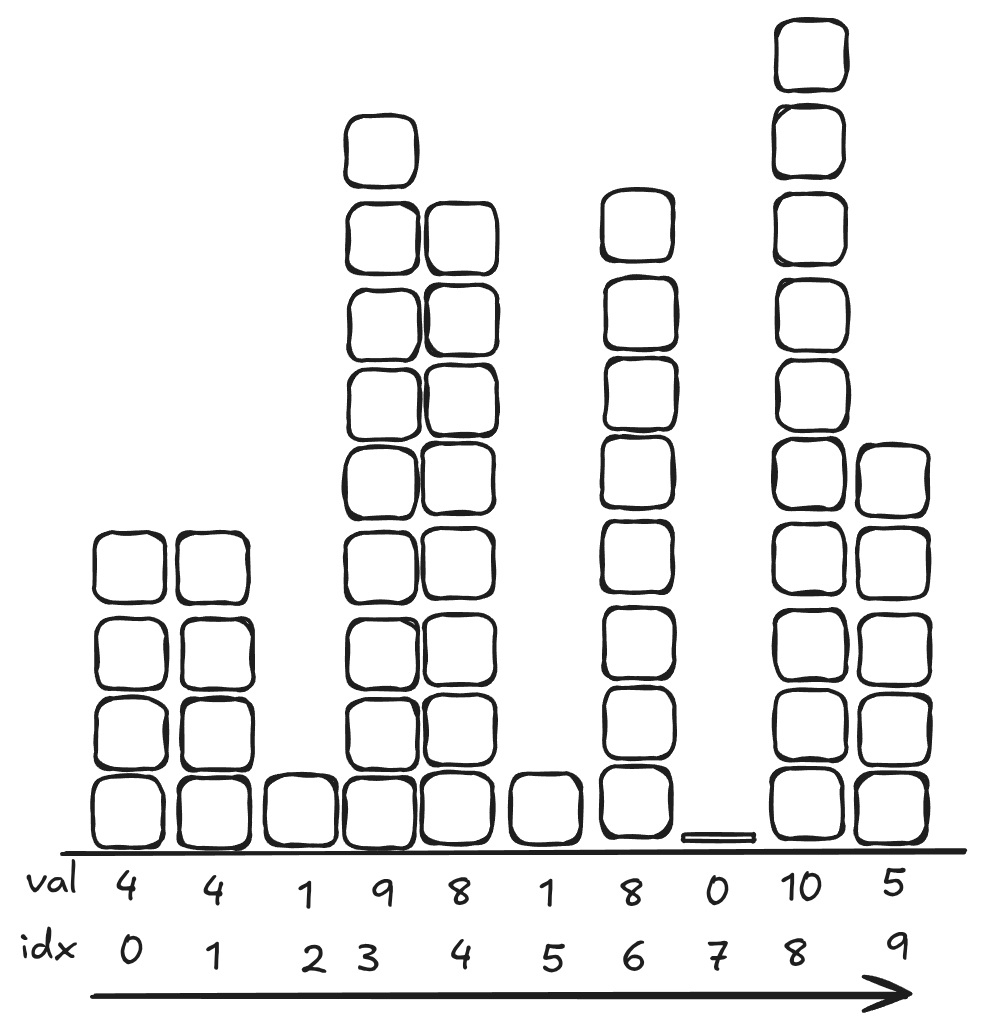

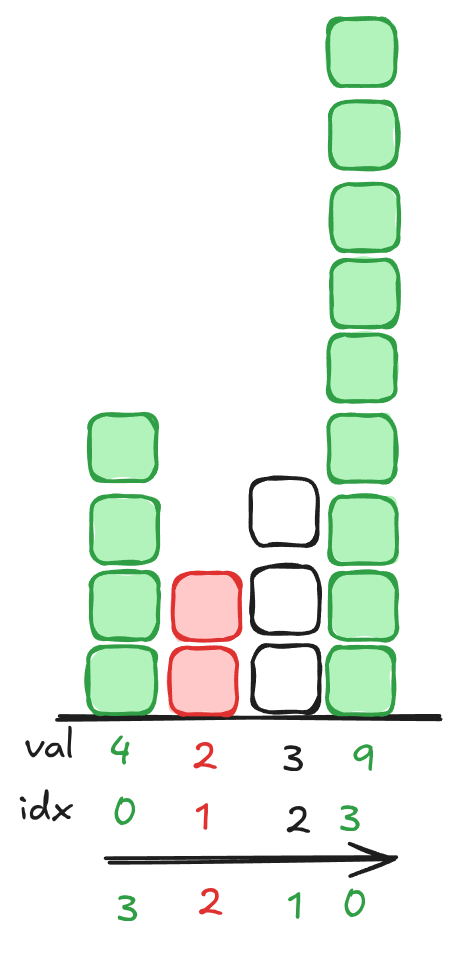

Spelled out, the basic idea looks like this. Say you have an array of numbers [4, 4, 1, 9, 8, 1, 8, 0, 10, 5]. Graphing this looks like this:

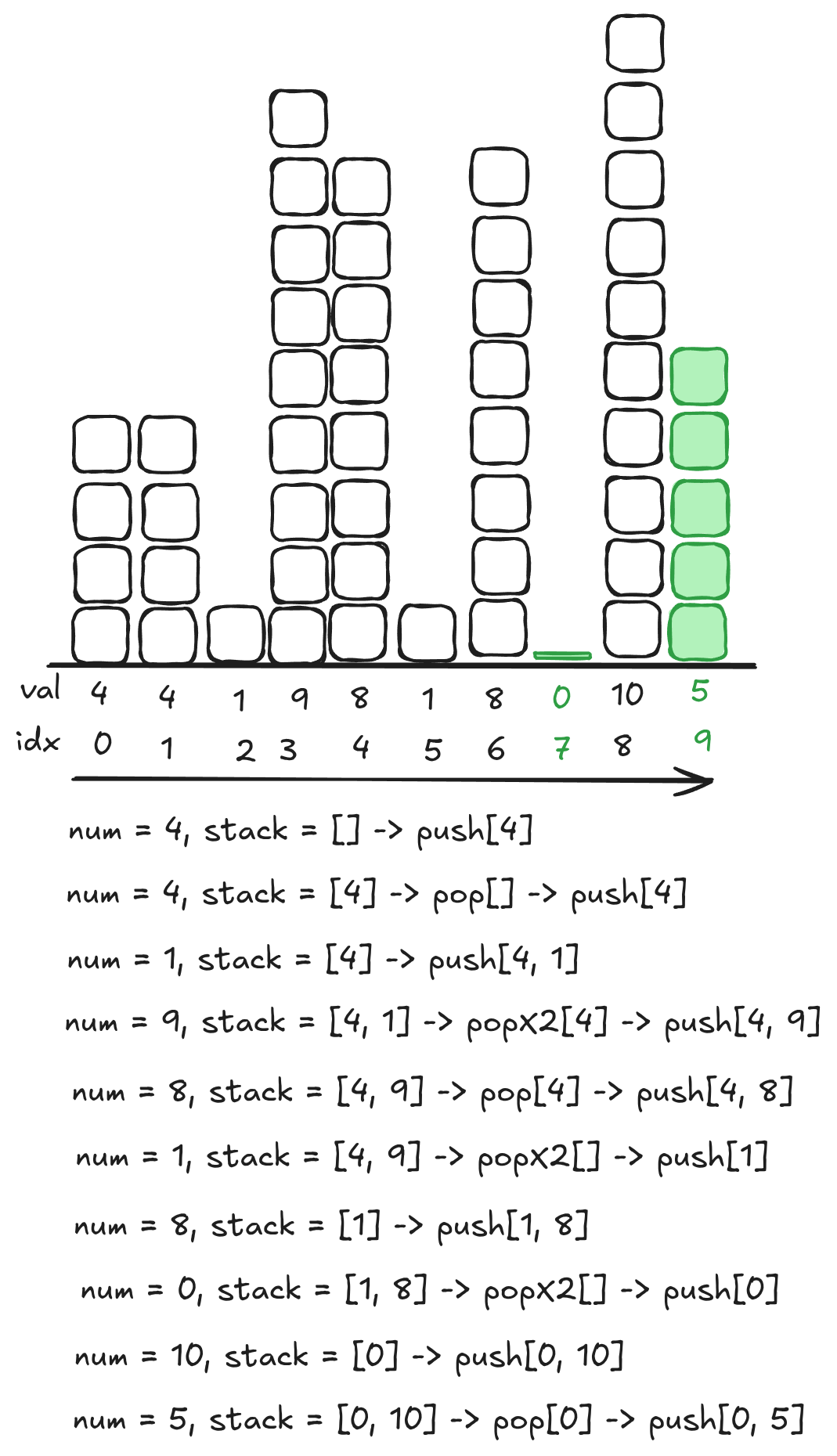

You’re going to iterate forwards, and when number is bigger than the back of the stack you’re going to pop until the back is smaller, then insert it. Take a second and think about which numbers are going to be selected in the end and how.

Not what you were expecting? Well, when I tried to do this at a glance I first thought it would be [4, 9, 10], then I realised a mistake and thought [0, 10], but after running it in Python it spat out [0, 5]! The key thing is that you always push the current element onto the stack in the classical variation.

items = [4, 4, 1, 9, 8, 1, 8, 0, 10, 5]

mono_stack = []

for item in items:

print(item, mono_stack)

while len(mono_stack) > 0 and mono_stack[-1] >= item:

mono_stack.pop()

mono_stack.append(item)

print('Forward increasing', mono_stack)

mono_stack = []

for item in reversed(items):

print(item, mono_stack)

while len(mono_stack) > 0 and mono_stack[-1] >= item:

mono_stack.pop()

mono_stack.append(item)

print('Backwards increasing', mono_stack)

mono_stack = []

for item in items:

print(item, mono_stack)

while len(mono_stack) > 0 and mono_stack[-1] <= item:

mono_stack.pop()

mono_stack.append(item)

print('Forwards decreasing', mono_stack)

mono_stack = []

for item in reversed(items):

print(item, mono_stack)

while len(mono_stack) > 0 and mono_stack[-1] <= item:

mono_stack.pop()

mono_stack.append(item)

print('Backwards decreasing', mono_stack)

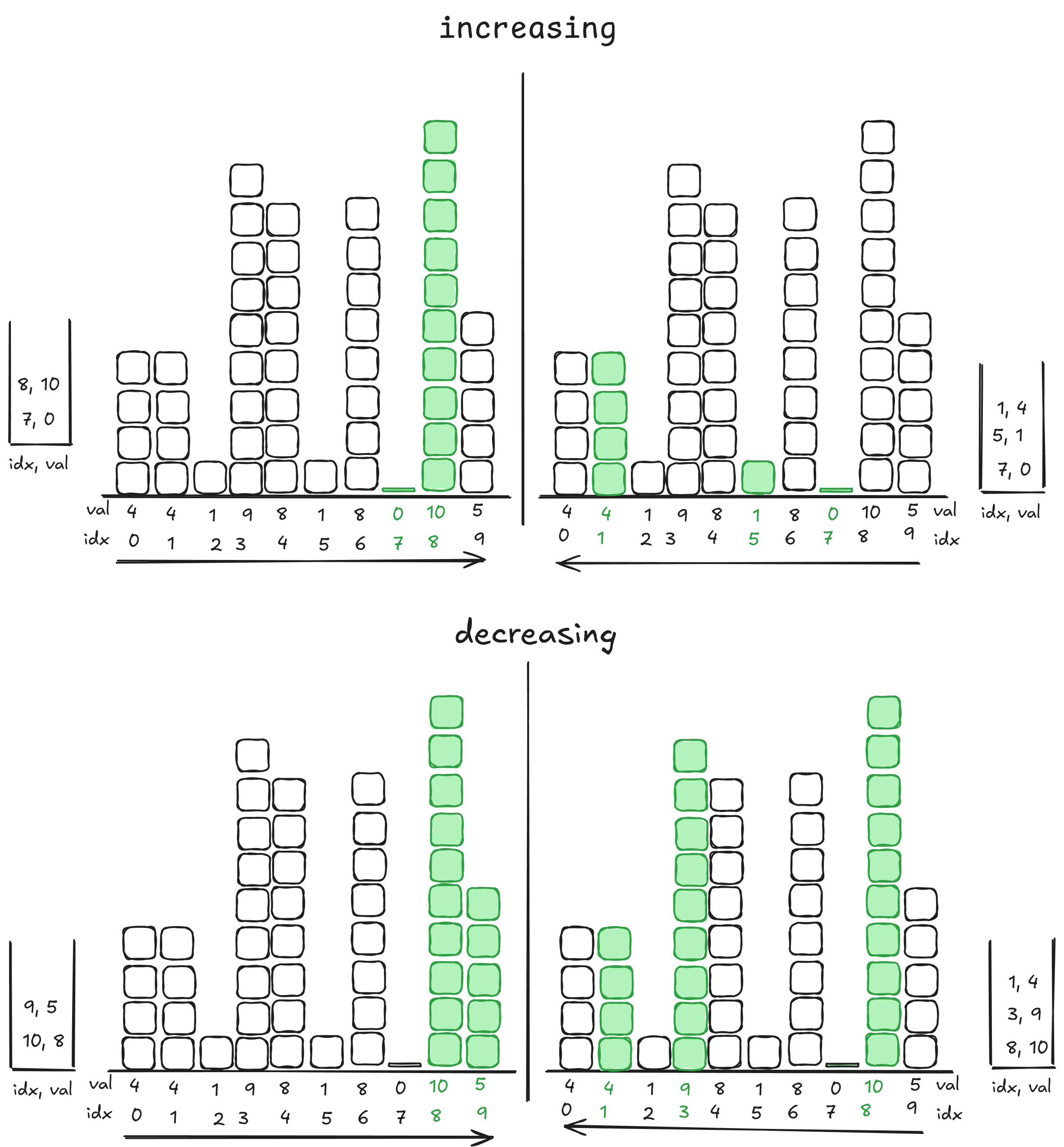

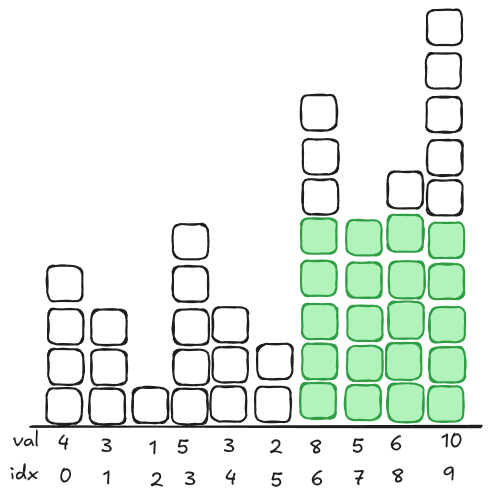

Wait, so what’s the point of this? We’re looking at the end state, but that’s kind of confusing. Let’s change the data, then it might make more sense.

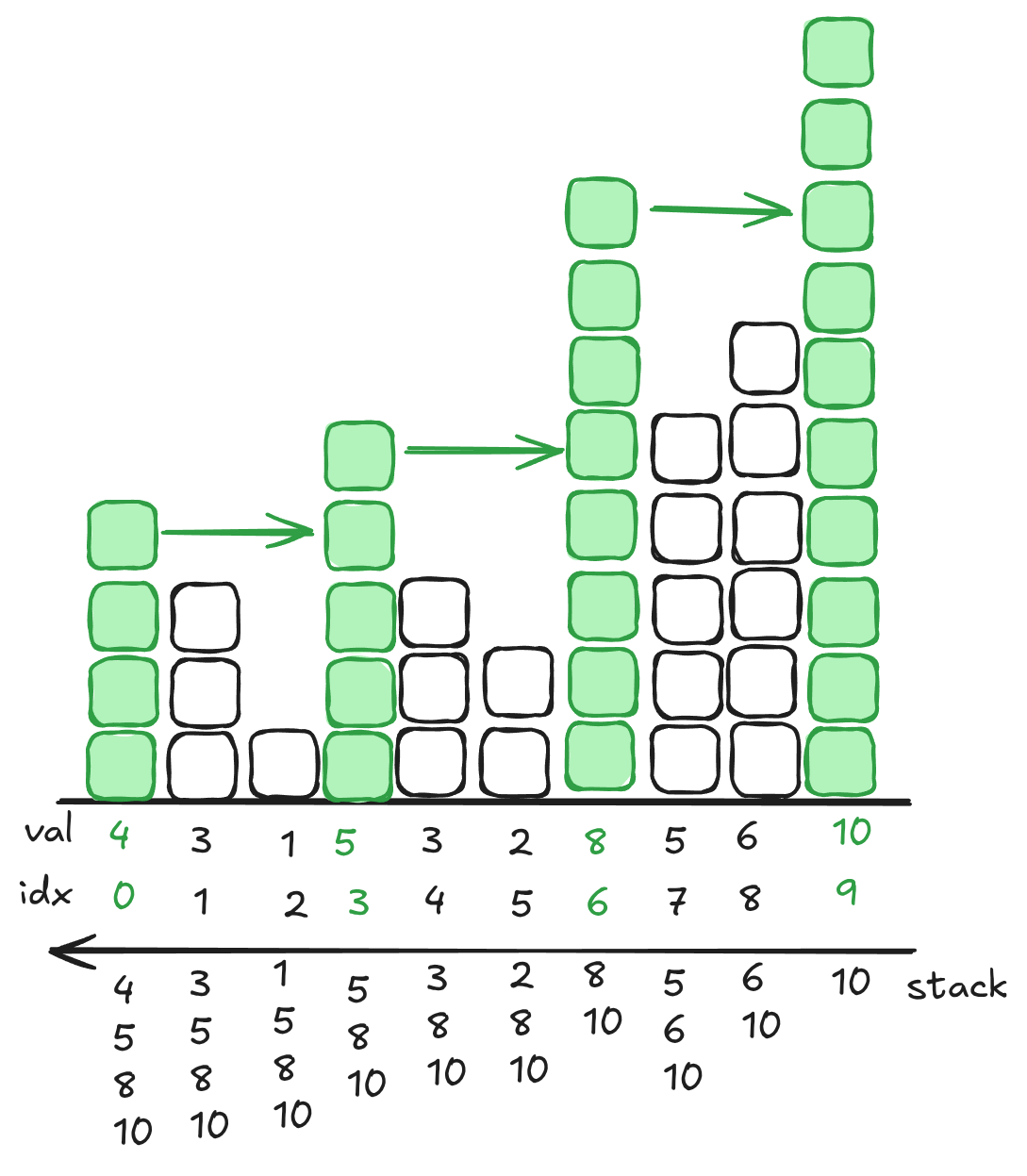

You can see that every number effectively has this scope, or shadow backwards. If you track the indexes as well, you can start doing things to this.

Patterns

Understanding the concept properly needs you to work through problems. You might be confused, or probably are confused since that was a high-level explanation. I’m going to break this into four patterns: nearest bound, range contribution, greedy reductions, and merging pairs. Understanding these requires you to work through problems and practice them.

Nearest Bound

The idea is that whenever you pop, your current number is the nearest greater than or lesser than element to the popped number. The classic problem here is [daily temperatures](https://leetcode.com/problems/daily-temperatures/description/. You’re given a set of temperatures where each number represents a day. Return an array containing the number of days you need to wait after the day for it to get warmer.

Look at that last diagram. It basically already has the answer in it! Well, not quite, because you’re going to have to do this incrementally. Here’s a counter example to for why that last diagram won’t work. If you only consider the end state, it’ll skip numbers:

Index 1 really only needs to wait for the next day, so it’s going to be wrong. However, if we go back to when index 3 was at the top of the stack, we can label 2 properly when we pop it out!

Now it should make more sense. Whenever you pop, label the days the popped entry needs to wait.

class Solution:

def dailyTemperatures(self, temps: List[int]) -> List[int]:

mono = []

answer = [0] * len(temps)

for day, temp in enumerate(temps):

while len(mono) > 0 and mono[-1][0] < temp:

_, idx = mono.pop()

answer[idx] = day - idx

mono.append((temp, day))

return answerRange Contribution

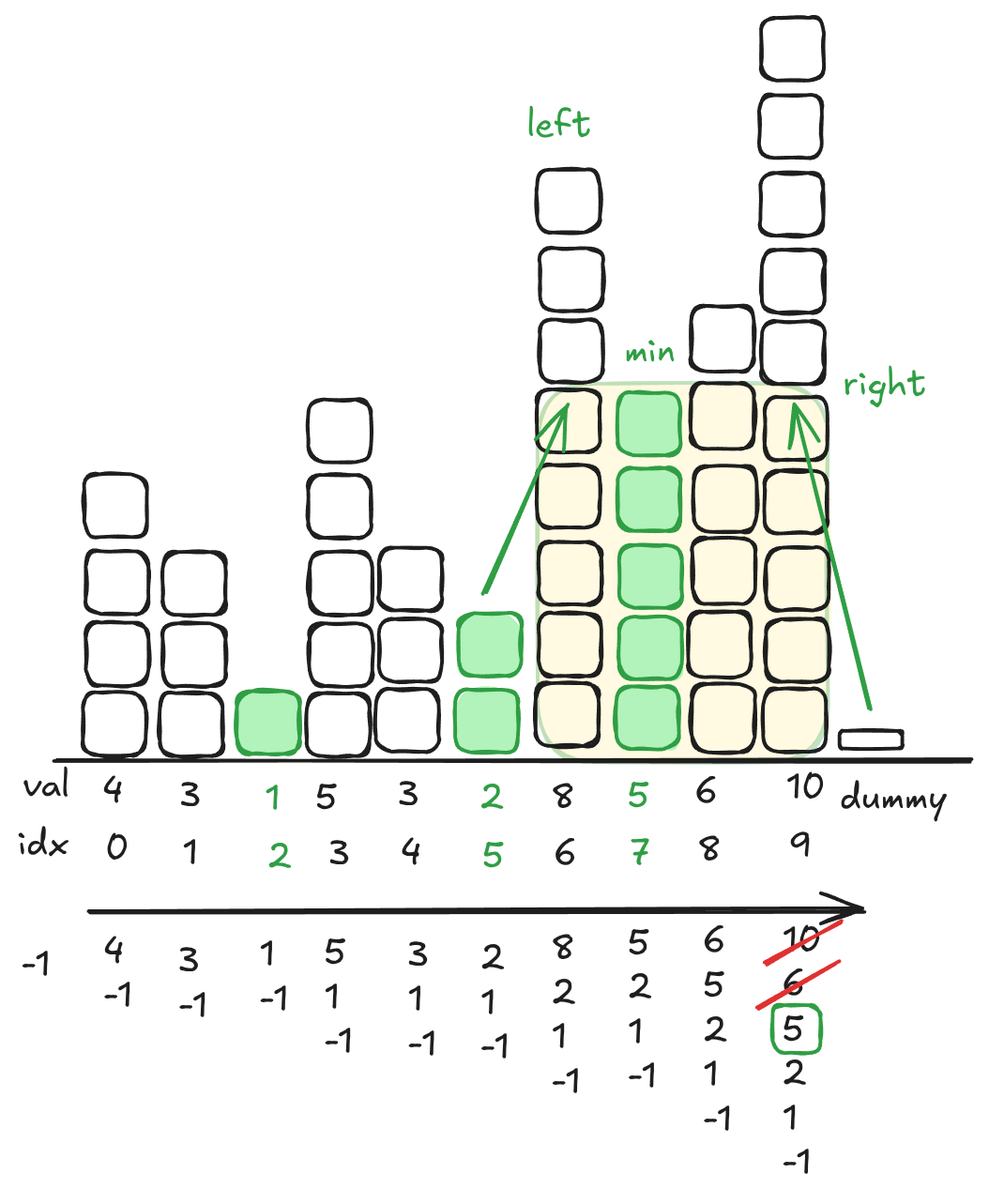

In range contribution, you aren’t just looking for a single number or a pair. Rather, you need the entire range across two numbers in a stack to contribute. You’re taking advantage of the invariant that the stack can identify the widest where , and is the minimum or the maximum in the range.

Largest Rectangle in a Histogram is the classic version of this problem. Bit strange though, since it’s a hard! The fundamental idea is that the whole range between two points contributes to your value. In this problem, it’s the minimum height in the range multiplied by the width of your range; the biggest rectangle.

You’re going to iterate from left to right with an increasing stack. Whenever you pop, you’re going to calculate the area, but it’s a bit weird.

- If our current number is less than the back of the stack, the rectangle is going to have to shrink because the top won’t be the minimum of the rectangle anymore.

- One left of our current number is the right side of the rectangle (dummy in the diagram)

- We pop out the top, and that’s going to be the minimum height in the rectangle

- To the right of the new top of the stack is the left side

This is pretty confusing. The image below should help. We’ve already popped 10 and 6 out. Our right is to the left of the dummy, the minimum is the 5, and the left side is one to the right of the 2.

class Solution:

def largestRectangleArea(self, heights: List[int]) -> int:

heights.append(0) # space filler

stack = [-1] # Initialize with -1 index as a left boundary

max_area = 0

for i, h in enumerate(heights):

while stack[-1] != -1 and h < heights[stack[-1]]:

height = heights[stack.pop()]

width = i - stack[-1] - 1

max_area = max(max_area, height * width)

stack.append(i)

return max_areaGreedy Reduction

In a greedy reduction, you’re filtering the content down into a result sequence and you’re using the stack to decide whether a new element is good enough to displace an old element. In essence, you’re usually given some budget and want to find the minimum thing according to some rule. Your invariant here is that at any step , the stack contains the optimal prefix of length that can be created with .

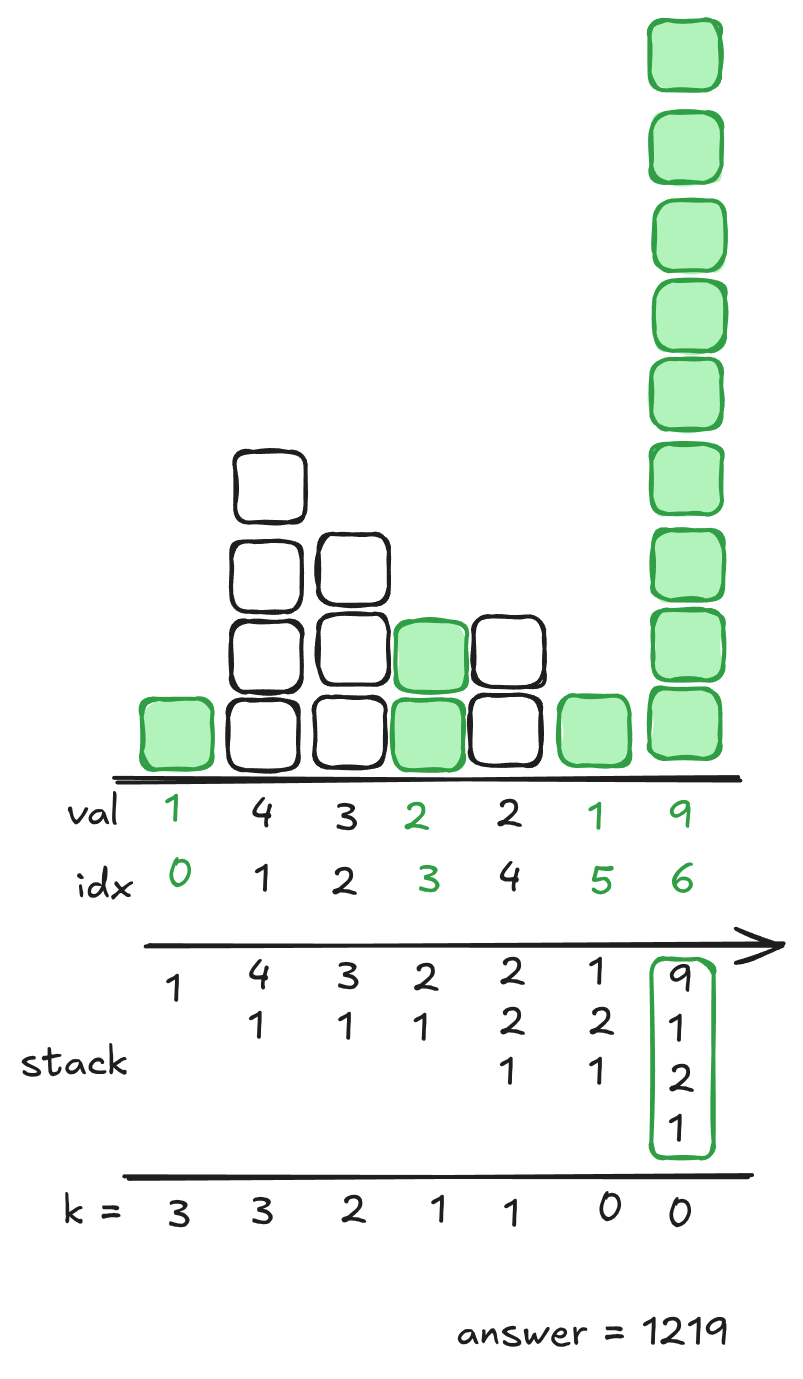

Remove K digits is the classical problem here. You’re given a number and a non-negative , return the smallest possible integer after you remove k digits from number. So you want to create an increasing mono stack, but you have a budget of k deletions. If you don’t use all of them, you can strip the front out of your number for the answer.

In the below image you can see working through this for 1432219.

- We append 1 → ,

- We append 4 → ,

- We pop because , spending a , then push in 3 → ,

- We pop because , spending a , then push in 2 → ,

- Push in 2 → ,

- We pop because , spending a , but now we’re out of budget! so we have to push in 1 → ,

- Even though , we have to push it in because we’re out of budget → ,

class Solution:

def removeKdigits(self, num: str, k: int) -> str:

mono = []

for digit in num:

while k > 0 and mono and mono[-1] > digit:

mono.pop()

k -= 1

mono.append(digit)

if k > 0: mono = mono[:-k]

ans = ''.join(mono).lstrip('0')

return ans if ans else '0'Merging pairs

In this, each element ‘dominates’ or ‘blocks’ another element if its shadow goes over it and it satisfies and some requirement. Your stack is maintaining a set of survivors that have not been blocked or absorbed.

Car fleet is the classical problem here. There are n cars driving some speed to reach a target, and you have each car’s position and speed. When a car catches up to another car, it absorbs it into a fleet that are driving next to each other. Return the number of individual fleets that arrive at the target.

First, we need to transform our data into arrival times, sorted by their initial position.

target = 12

positions = [10,8,0,5,3]

speeds = [2,4,1,1,3]

# note that we sort by positions here!

arrivals = [(target - p) / s for p, s in sorted(zip(positions, speeds), reverse=True)]

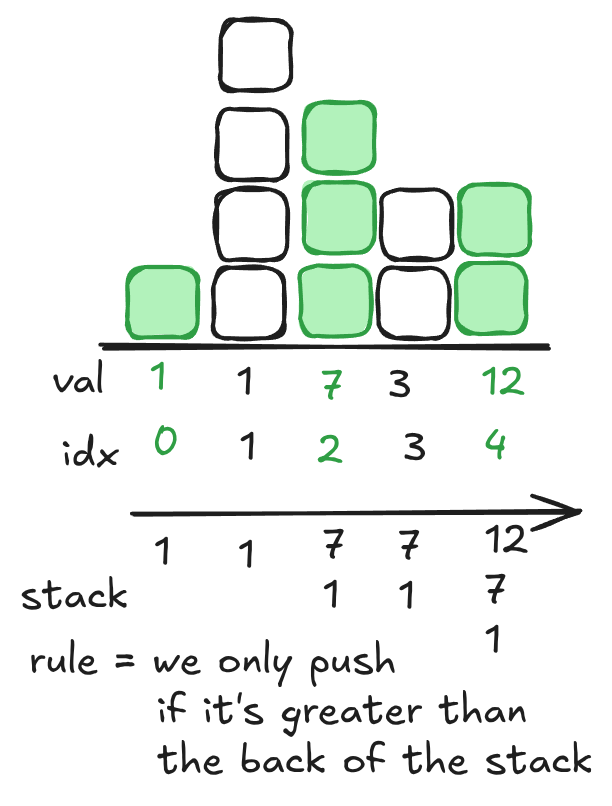

# arrivals == [1.0, 1.0, 7.0, 3.0, 12.0]So now we have the arrival times. That part tends to be surprisingly difficult if you’re doing this from scratch. If an arrival time is before a car whose position was in front of it, it must have overtaken it. So, we should only append to the stack if it increases the size of the back.

class Solution:

def carFleet(self, target: int, position: List[int], speed: List[int]) -> int:

arrivals = [(target - p) / s for p, s in sorted(zip(position, speed), reverse=True)]

stack = []

for arrival in arrivals:

if not stack or arrival > stack[-1]:

stack.append(arrival)

return len(stack)Looking at that code, you could get rid of the stack entirely!

class Solution:

def carFleet(self, target: int, position: List[int], speed: List[int]) -> int:

arrivals = [(target - p) / s for p, s in sorted(zip(position, speed), reverse=True)]

best = float('-inf')

size = 0

for arrival in arrivals:

if arrival > best:

best = arrival

size += 1

return sizeThis is how I used to picture monotonic stacks, rather than the pop-first approach.

Further extensions

- Monotonic deque - you maintain a monotonic stack, but need to pop from both sides for some requirement. This is similar to a sliding window.

- Range contribution can change into a combinatorial problem, where you need to do something with all possible subarrays. This is similar to a sliding window.

- Finding buckets of space, like trapping rain water.

Conclusion

There are probably more patterns. I haven’t done a massive number of monotonic stack questions, but this is probably a reasonable introduction to them. To get better, I suggest going to:

and doing increasingly difficult problems. The real skill here is learning to identify which type of approach to take.

zyros

zyros